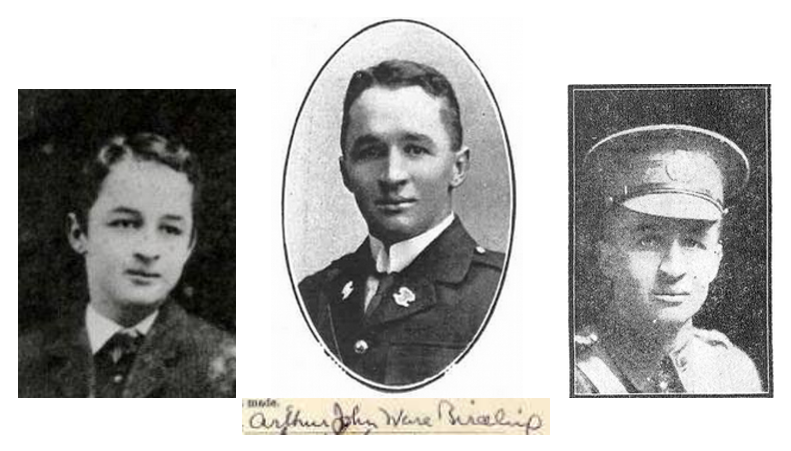

Arthur John (Jackie) Ware Birdling

Birth: 6 Nov 1890, Hornby Christchurch

Death: 20 Sep 1916, France

Burial: Albert, Department de la Somme, Picardie, France

Arthur John Ware Birdling was born in Hornby, just west of Christchurch, New Zealand, on November 6, 1890. Affectionately known as Jackie or Jack, he was the first of the four children of Arthur John Birdling and Emily Agnes Callaghan. His parents were landed gentry, having both been children of immigrants who had become successful in the cattle-raising trade. Jackie was raised on one of his grandfather’s family farms. When he was 11 in 1902, his grandfather William died, and the family moved to Lansdown, the larger farm at Halswell.

Like his father, Jack was a child of privilege, but he was not spoiled. The family was more than stable financially, and he wanted for nothing. As the oldest scion of landed gentry, he had a sense of noblesse oblige instilled in him from an early age. He was responsible for his younger siblings and knew the laborers on the farm would one day be counting on him for their livelihoods.

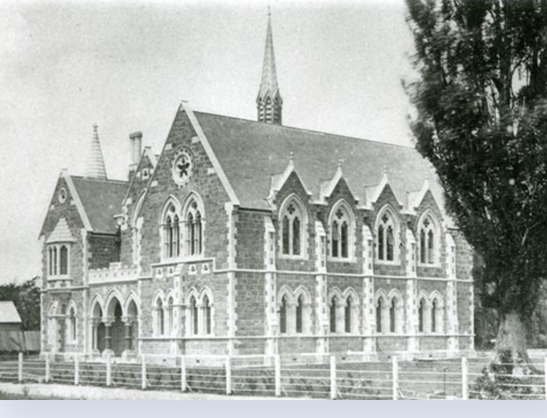

Jack had an excellent education. He attended Halswell Public School and then Boys’ High School in 1906 and 1907. Christchurch Boys’ High School opened on May of 1881 in response to concerns of the staff of Canterbury College (now Canterbury University) that the students were not sufficiently trained. Boys’ High School has essentially been a college prep school from the beginning. According to the history page of the Boys’ High webpage:

Death: 20 Sep 1916, France

Burial: Albert, Department de la Somme, Picardie, France

Arthur John Ware Birdling was born in Hornby, just west of Christchurch, New Zealand, on November 6, 1890. Affectionately known as Jackie or Jack, he was the first of the four children of Arthur John Birdling and Emily Agnes Callaghan. His parents were landed gentry, having both been children of immigrants who had become successful in the cattle-raising trade. Jackie was raised on one of his grandfather’s family farms. When he was 11 in 1902, his grandfather William died, and the family moved to Lansdown, the larger farm at Halswell.

Like his father, Jack was a child of privilege, but he was not spoiled. The family was more than stable financially, and he wanted for nothing. As the oldest scion of landed gentry, he had a sense of noblesse oblige instilled in him from an early age. He was responsible for his younger siblings and knew the laborers on the farm would one day be counting on him for their livelihoods.

Jack had an excellent education. He attended Halswell Public School and then Boys’ High School in 1906 and 1907. Christchurch Boys’ High School opened on May of 1881 in response to concerns of the staff of Canterbury College (now Canterbury University) that the students were not sufficiently trained. Boys’ High School has essentially been a college prep school from the beginning. According to the history page of the Boys’ High webpage:

Some of the key themes of the school’s history have been the successes of its old boys and their influence in all facets of New Zealand life. Remarkably a number of Boys’ High old boys have gone on to become principals of other schools. Two old boys number amongst the 11 Headmasters of Christchurch Boys’ High School. Other than education, old boys have made their mark in the law, commerce, medicine, engineering, politics, literature, sport, the performing arts and the military.

Perhaps New Zealand’s greatest soldier, Sir Howard Kippenberger, attended Boys’ High School as did his fellow Brigadier James Burrows. In the 1960’s New Zealand’s Army, Navy, and Airforce were all lead by old boys. 359 old boys have died fighting for New Zealand, and the school’s ANZAC service has special significance.

The sense of belonging, partly generated by the success and sacrifice of its old boys, is another integral feature of the school’s history. The school has always seen itself as a community school and has evoked a loyalty amongst this community that has furthered the success of its students.

The influence of the Masters and Teachers on the boys of the school has also been felt through the school’s time. From Charles Bevan Brown, Headmaster from 1883 until 1920, to Masters returning from war, to great music teachers and sports coaches, the character and influence of these men and women has shaped the school and its pupils.

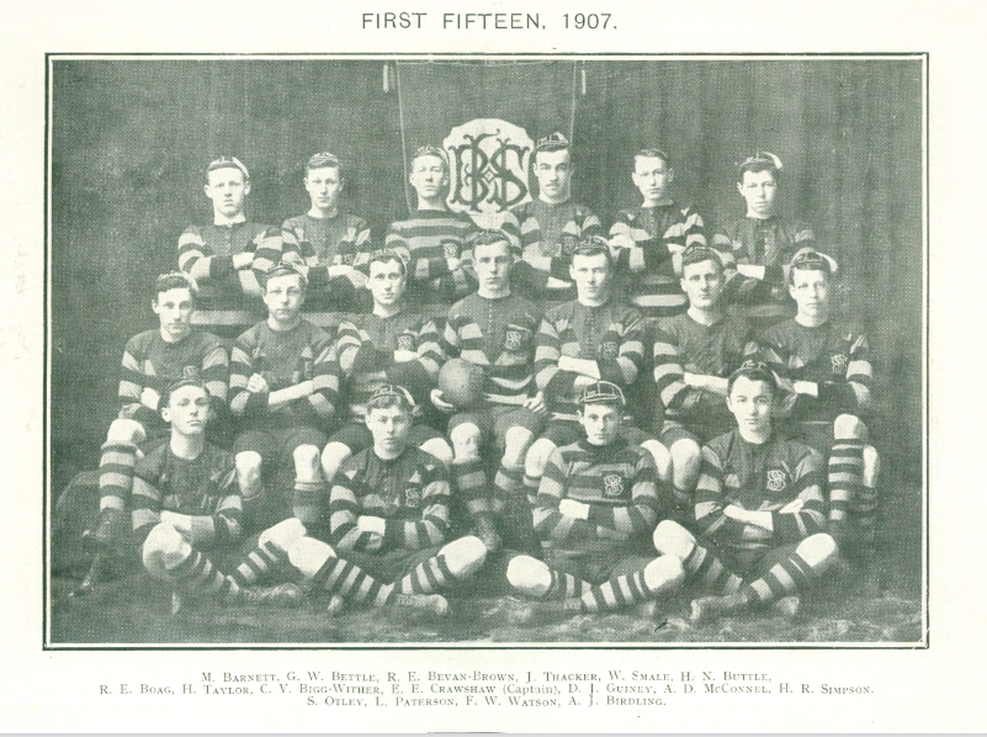

At Boys’ High, Jackie enjoyed history best among his subjects, but he really came into his own playing rugby. He made the third fifteen his first year and earned his cap for the first fifteen his second. He played forward. According to Florugby.com:

In almost all cases, forwards tend to be your bigger, stronger, and slower lads, who do most of the tackling, rucking, and hitting that goes on in a game. They do what they would consider most of the tough work and hard grafting required on a rugby pitch. Without them, the skinnies in the backline wouldn't be able to do anything.

The forwards are ultimately categorized as the eight players who take part in a scrum. The positions that are involved in the scrum include the props, the hooker, the locks, the flankers, and the No. 8.

At 5’ 10” and 175 lbs., Jackie was likely a prop.

Props are always #1 and #3 on the field, and are often two of the heaviest players on the pitch. They line up in the front row of the scrum, on either side of the hooker, and their primary job is to lead the forward pack at scrum time. What they do in the scrum is extremely taxing on the body, and it takes both an extremely strong and extremely tough player to do it. In addition, they often do a lot of lifting during lineouts, as well as plenty of rucking, tackling, and ball carrying in open play.

According to his Honors Roll biography in The Press (1916) he was "a fine stamp of player."

Perhaps New Zealand’s greatest soldier, Sir Howard Kippenberger, attended Boys’ High School as did his fellow Brigadier James Burrows. In the 1960’s New Zealand’s Army, Navy, and Airforce were all lead by old boys. 359 old boys have died fighting for New Zealand, and the school’s ANZAC service has special significance.

The sense of belonging, partly generated by the success and sacrifice of its old boys, is another integral feature of the school’s history. The school has always seen itself as a community school and has evoked a loyalty amongst this community that has furthered the success of its students.

The influence of the Masters and Teachers on the boys of the school has also been felt through the school’s time. From Charles Bevan Brown, Headmaster from 1883 until 1920, to Masters returning from war, to great music teachers and sports coaches, the character and influence of these men and women has shaped the school and its pupils.

At Boys’ High, Jackie enjoyed history best among his subjects, but he really came into his own playing rugby. He made the third fifteen his first year and earned his cap for the first fifteen his second. He played forward. According to Florugby.com:

In almost all cases, forwards tend to be your bigger, stronger, and slower lads, who do most of the tackling, rucking, and hitting that goes on in a game. They do what they would consider most of the tough work and hard grafting required on a rugby pitch. Without them, the skinnies in the backline wouldn't be able to do anything.

The forwards are ultimately categorized as the eight players who take part in a scrum. The positions that are involved in the scrum include the props, the hooker, the locks, the flankers, and the No. 8.

At 5’ 10” and 175 lbs., Jackie was likely a prop.

Props are always #1 and #3 on the field, and are often two of the heaviest players on the pitch. They line up in the front row of the scrum, on either side of the hooker, and their primary job is to lead the forward pack at scrum time. What they do in the scrum is extremely taxing on the body, and it takes both an extremely strong and extremely tough player to do it. In addition, they often do a lot of lifting during lineouts, as well as plenty of rucking, tackling, and ball carrying in open play.

According to his Honors Roll biography in The Press (1916) he was "a fine stamp of player."

The Duke of Wellington said that the Battle of Waterloo was won on the playing fields of Eton. This has a meaning that says Britain's military success was based on the values taught to school boys in their public schools. (Eton was the most popular of these schools.) A century later, the assumption was that this would be true in the coming war.

After two years, Jackie decided he had learned enough and returned home without graduating and went to work on the farm. He also became interested in a local girl named Christina McGilvray.

After two years, Jackie decided he had learned enough and returned home without graduating and went to work on the farm. He also became interested in a local girl named Christina McGilvray.

Christina Alice McGilvray was the second of the three daughters of Duncan McGilvray and Annie Johnson. She was born on January 12, 1892, in Mount Grey, Canterbury, New Zealand.

Her parents were both Presyberian, Scottish immigrants. Her father was born in 1851 at. Burg Farm, Kilfinichen, Mull, Argyllshire, Scotland. Her mother was born in 1865 in Urquhart, Moaryshire. They had come separately to New Zealand in the mid-1880s and married at Landsdowne in 1889. Duncan was a farmer and Christina grew up on his farm near Darfield.

Jack had every intention of marrying her and had even given her an engagement ring. When the War broke out, he decided to wait until he had served and come home. He did not think it would be fair to her for them to marry and then for him to leave her behind for the duration.

Jack had interested himself greatly in the Territorial Movement. The Territorial Force was a part-time volunteer component of the British Army, created in 1908 to augment British land forces without resorting to conscription. It was designed to reinforce the regular army in expeditionary operations abroad, but, because of political opposition it, was mostly assigned to home defense. Members were liable for service anywhere in the UK but could not be compelled to serve overseas.

The Territorial movement as a social push strongly encouraged all young men to be prepared to serve in the military. Ultimately, New Zealand's greatest contribution to the war effort was to supply 120,000 service personnel, nearly 100,000 of whom served overseas. The foundations of this massive mobilization had been laid in the years leading up to World War I through organizations such as the Boy Scouts and the YMCA and through the introduction of compulsory military training in 1909. Much of the rhetoric around the movement was jingoistic in nature. As one essayist wrote in The Otago Witness (1910):

…And yet this decadent British race—this weakening nation of ours, with a mere handful of troops—one soldier for every 12,000 of the native population [in India]—still holds sway over the destinies of this strange and mysterious race. A feeble hold, which may be thrown off at any moment, the advocates of decadency may sneer, yet it is a hold which has endured for 150 years, and one which will endure as long as the right spirit animates the nation.

During the last three years, we have seen the use of the Territorial movement, which has brought out the best trait in national character—patriotism to one's country; compulsory service in the colonies is about to replace Volunteering as a stronger scheme, wherein the old adage "defence, not defiance" will be embodied and the interchange between England and her sons of advanced military ideas is welding the nation into a systematized and homogeneous whole. Glancing round the Empire, one cannot fail to be impressed with the strong current of thought and work which under a regime of peace and prosperity underlie all the actions of its people…

Growing international tension meant that there was little opposition to the passing of a new Defense Act in December 1909. Besides replacing the Volunteer Force with a Territorial Force, it also introduced compulsory military training. All boys aged between 12 and 14 had to undergo 52 hours of physical training each year as Junior Cadets. This requirement was dropped in 1912.

Before March of 1914, Jackie had been in the Territorial Force and risen to the rank of Corporal in the Canterbury Mounted Rifles. When War broke out in August, he, his brother Gerald, and four of their cousins rushed to Haswell to enlist. Because of his time in the Territorial Force, Jackie was recommended for and passed the Lieutenants’ exam. On March 5, 1915, he was promoted to 2nd Lieutenant and sent to Trentham Military Base for officer training. While he was there, he would have received news that his cousin Reggie had been killed at Banchop Hill, Gallipoli.

Finally, in November, he boarded ship in Wellington and headed for Egypt and the Suez Canal. He arrived in Alexandria in December and moved to Ismailia, a town on the west back of the canal, for further training. While in Ismailia, he was promoted to 1st Lieutenant and transferred to the 6th Reinforcement Canterbury Regiment, 2nd Battalion. In March, 1916, he boarded the SS Haverford at Port Said and sailed for France and the Somme.

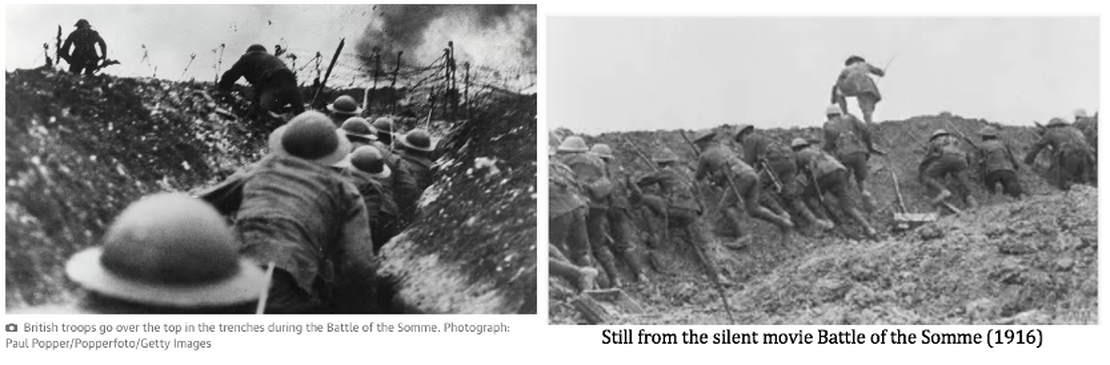

In 1916, the Western Front was a quagmire. The prevailing military philosophy of von Clausewitz and Wellington that relied upon frontal assault was almost 100 years behind the advances of military technology. General Haig, in particular, felt that anything but going over the top was somehow not manly. All the elon, gallantry, and patriotism that could be learned on the rugby pitches of the Empire could not prepare soldiers for the impersonal slaughter of artillery barrages, withering machine gun fire, and clouds of mustard gas that mechanized war threw at them.

With a bloody war of attrition going on at Verdun, the British had decided to try and break that stalemate by attacking German-held territory along the River Somme. They first launched a week-long artillery assault. This, they thought, would weaken German lines enough that waves of troops could then march across no-man’s-land to overrun them. On 1 July 1916, the first wave of eleven British and five French divisions were ordered over the top. The Germans, however, were still strong (the plans of the offensive had been leaked!), and vast numbers of Allied troops were mowed down by machine-gun fire. By the end of the day, 56,000 British soldiers were cut down, most never getting 10 yards beyond they trench. Haig doubled down. Over the following weeks, more troops were sent out and cut down. By November when the offensive was finally called off, over 3 million men fought there and over a million died, making it one of the most deadly battles of the War. [Incidentally, there was a 1916 silent film of the Battle of the Somme. Lloyd George called it the most important movie of the War. It is currently available on Amazon Prime.]

Her parents were both Presyberian, Scottish immigrants. Her father was born in 1851 at. Burg Farm, Kilfinichen, Mull, Argyllshire, Scotland. Her mother was born in 1865 in Urquhart, Moaryshire. They had come separately to New Zealand in the mid-1880s and married at Landsdowne in 1889. Duncan was a farmer and Christina grew up on his farm near Darfield.

Jack had every intention of marrying her and had even given her an engagement ring. When the War broke out, he decided to wait until he had served and come home. He did not think it would be fair to her for them to marry and then for him to leave her behind for the duration.

Jack had interested himself greatly in the Territorial Movement. The Territorial Force was a part-time volunteer component of the British Army, created in 1908 to augment British land forces without resorting to conscription. It was designed to reinforce the regular army in expeditionary operations abroad, but, because of political opposition it, was mostly assigned to home defense. Members were liable for service anywhere in the UK but could not be compelled to serve overseas.

The Territorial movement as a social push strongly encouraged all young men to be prepared to serve in the military. Ultimately, New Zealand's greatest contribution to the war effort was to supply 120,000 service personnel, nearly 100,000 of whom served overseas. The foundations of this massive mobilization had been laid in the years leading up to World War I through organizations such as the Boy Scouts and the YMCA and through the introduction of compulsory military training in 1909. Much of the rhetoric around the movement was jingoistic in nature. As one essayist wrote in The Otago Witness (1910):

…And yet this decadent British race—this weakening nation of ours, with a mere handful of troops—one soldier for every 12,000 of the native population [in India]—still holds sway over the destinies of this strange and mysterious race. A feeble hold, which may be thrown off at any moment, the advocates of decadency may sneer, yet it is a hold which has endured for 150 years, and one which will endure as long as the right spirit animates the nation.

During the last three years, we have seen the use of the Territorial movement, which has brought out the best trait in national character—patriotism to one's country; compulsory service in the colonies is about to replace Volunteering as a stronger scheme, wherein the old adage "defence, not defiance" will be embodied and the interchange between England and her sons of advanced military ideas is welding the nation into a systematized and homogeneous whole. Glancing round the Empire, one cannot fail to be impressed with the strong current of thought and work which under a regime of peace and prosperity underlie all the actions of its people…

Growing international tension meant that there was little opposition to the passing of a new Defense Act in December 1909. Besides replacing the Volunteer Force with a Territorial Force, it also introduced compulsory military training. All boys aged between 12 and 14 had to undergo 52 hours of physical training each year as Junior Cadets. This requirement was dropped in 1912.

Before March of 1914, Jackie had been in the Territorial Force and risen to the rank of Corporal in the Canterbury Mounted Rifles. When War broke out in August, he, his brother Gerald, and four of their cousins rushed to Haswell to enlist. Because of his time in the Territorial Force, Jackie was recommended for and passed the Lieutenants’ exam. On March 5, 1915, he was promoted to 2nd Lieutenant and sent to Trentham Military Base for officer training. While he was there, he would have received news that his cousin Reggie had been killed at Banchop Hill, Gallipoli.

Finally, in November, he boarded ship in Wellington and headed for Egypt and the Suez Canal. He arrived in Alexandria in December and moved to Ismailia, a town on the west back of the canal, for further training. While in Ismailia, he was promoted to 1st Lieutenant and transferred to the 6th Reinforcement Canterbury Regiment, 2nd Battalion. In March, 1916, he boarded the SS Haverford at Port Said and sailed for France and the Somme.

In 1916, the Western Front was a quagmire. The prevailing military philosophy of von Clausewitz and Wellington that relied upon frontal assault was almost 100 years behind the advances of military technology. General Haig, in particular, felt that anything but going over the top was somehow not manly. All the elon, gallantry, and patriotism that could be learned on the rugby pitches of the Empire could not prepare soldiers for the impersonal slaughter of artillery barrages, withering machine gun fire, and clouds of mustard gas that mechanized war threw at them.

With a bloody war of attrition going on at Verdun, the British had decided to try and break that stalemate by attacking German-held territory along the River Somme. They first launched a week-long artillery assault. This, they thought, would weaken German lines enough that waves of troops could then march across no-man’s-land to overrun them. On 1 July 1916, the first wave of eleven British and five French divisions were ordered over the top. The Germans, however, were still strong (the plans of the offensive had been leaked!), and vast numbers of Allied troops were mowed down by machine-gun fire. By the end of the day, 56,000 British soldiers were cut down, most never getting 10 yards beyond they trench. Haig doubled down. Over the following weeks, more troops were sent out and cut down. By November when the offensive was finally called off, over 3 million men fought there and over a million died, making it one of the most deadly battles of the War. [Incidentally, there was a 1916 silent film of the Battle of the Somme. Lloyd George called it the most important movie of the War. It is currently available on Amazon Prime.]

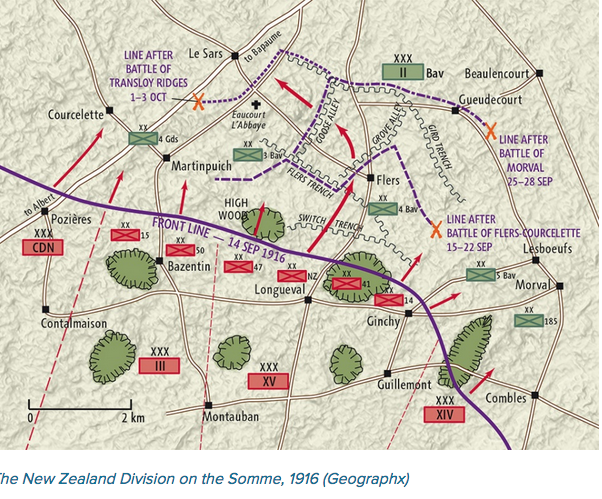

On September 15th near the village of Longueval, the New Zealand Division’s turn came. This was to be their first major engagement on the Western Front. Around 6,000 New Zealand soldiers went over the top at 6.20 a.m. By the end of the day, they had achieved their objective and helped take the village of Flers, but 600 of them lay dead. Over the coming days, the New Zealand Division helped capture Morval and Thiepval Ridge. These were small victories, however, and casualties remained horrifically high. Gerald was one of those wounded near Flers, on September 16th. He was shipped to London to recuperate before heading back to New Zealand and serving in the Home Guard until 1919.

Arthur John Ware Birdling died on September 20, 1916 at the Battle of Goose Alley, near Flers, France. He was 26 years old. As a 1st Lieutenant, Jack would have been at the front of his troops leading the assault and likely the first man into the German trench. According to a letter to his mother from Lt. V.E. McGowan (later published in Jack’s school magazine):

…It was the night of September 20th that Canterbury had to push forward and were getting a sad time. The officers were all killed in this advance…Just as your son was jumping into the German trench, he was shot just below the heart. He got into the trench, gave orders to the men as to what they must do; in fact, he several times said “Bomb them right down the trench, boys.” He was sitting on the first step of the trench. He gradually lost consciousness, and when the stretcher bearers took him out, he was quite unconscious and died just before they reached the field dressing station. He is buried in the soldiers’ cemetery just before going into Flers. On the right side close to the road. There is a little cross with his number and name at his grave.

The London Gazette and other papers would publish information on losses of soldiers who were mentioned in official dispatches. Jack was mentioned:

Operations on Somme - 20th September to 2nd October 1916. This officer has shown great gallantry and devotion to duty on several occasions and especially on the night of the 20th/21st September, 1916 in the attack on Goose Alley and Drop Alley, south east of Flers, when he received wounds which proved fatal.

The offensive failed disastrously. The New Zealanders were withdrawn in October and the offensive was called off on November 18th. Only 12 kilometers of ground were gained—at the cost of 650,000 allied and 500,000 German lives. That is 29.2 lives per foot, or one dead boy for every 0.4 inches. One of those dead boys was Jackie. Jack’s name is on the ANZAC Memorial at Caterpillar Valley, Department de la Somme, Picardie, France. He was worth so much more than that half inch.

Arthur John Ware Birdling died on September 20, 1916 at the Battle of Goose Alley, near Flers, France. He was 26 years old. As a 1st Lieutenant, Jack would have been at the front of his troops leading the assault and likely the first man into the German trench. According to a letter to his mother from Lt. V.E. McGowan (later published in Jack’s school magazine):

…It was the night of September 20th that Canterbury had to push forward and were getting a sad time. The officers were all killed in this advance…Just as your son was jumping into the German trench, he was shot just below the heart. He got into the trench, gave orders to the men as to what they must do; in fact, he several times said “Bomb them right down the trench, boys.” He was sitting on the first step of the trench. He gradually lost consciousness, and when the stretcher bearers took him out, he was quite unconscious and died just before they reached the field dressing station. He is buried in the soldiers’ cemetery just before going into Flers. On the right side close to the road. There is a little cross with his number and name at his grave.

The London Gazette and other papers would publish information on losses of soldiers who were mentioned in official dispatches. Jack was mentioned:

Operations on Somme - 20th September to 2nd October 1916. This officer has shown great gallantry and devotion to duty on several occasions and especially on the night of the 20th/21st September, 1916 in the attack on Goose Alley and Drop Alley, south east of Flers, when he received wounds which proved fatal.

The offensive failed disastrously. The New Zealanders were withdrawn in October and the offensive was called off on November 18th. Only 12 kilometers of ground were gained—at the cost of 650,000 allied and 500,000 German lives. That is 29.2 lives per foot, or one dead boy for every 0.4 inches. One of those dead boys was Jackie. Jack’s name is on the ANZAC Memorial at Caterpillar Valley, Department de la Somme, Picardie, France. He was worth so much more than that half inch.

Twelve days before the offensive where he gave up his life, Jack wrote to his brother Gerry, who was in hospital in England:

Dear old Geb,

Just a few lines. I got your short note saying you had come out of the big scrap all right. I was so pleased… Since we came out of the trenches, we have been ‘touring’ on foot—with full packs, mind you—all over the country.

We are just about to go into the big battle that is raging over here. This will be the last letter I’ll be able to get away to you for some time. We are quite close to it now – the thunder of the big guns is tremendous and as I write this, I can see the flashes of the big ones. You may have seen a few big guns firing, but you will never see them in the countless numbers as we see them over here. It is simply gigantic and the rumble is huge….

Well, old chap, I trust to God to come out of this all right. You may depend we’ll give as good as we take, and better.

So, cheeroh old sport. I’ll write at the first opportunity. Best wishes to all the boys.

Your loving brother

Jack

In his handwritten Last Will and Testament, Jack left his share of the Callaghan estate to his mother, “if it was lawful,” and to his two brothers if not. He also left Gerald is gold watch and Huia his watch chain. On the back he wrote:

I have not mentioned my father or Eileen. Re Eileen, I have mentioned Ger and Huia because I think they need more of the world’s goods in order to make homes. I love Eileen no less than the others.

To my dear old father, as with mother, I leave for ever all the best love and thoughts possible.

Should fate cause you to read this, do so with pride, for I shall have given my life for a just and righteous cause and will have held up the honour of my good old grandfather’s name.

Jackie also left all his money in the Post Office Savings Bank to his fiancé, Christina.

A very small appreciation of this noble girl whom I would have married before I left NZ, but did not because I did not think it right or fair to her under the circumstances. I wish her to get a good pendant, like my mother's, with this money. The ring she has is also hers ("to do as she likes" is crossed out) for all time.

After nine months mourning, she would marry Alexander Gillanders on July 4, 1917. They had one son whom she named Duncan after her father and live until 1983, having reached the age of 91. Whether she kept the ring all that time is unknown.

The New Zealand government gave a small stipend to the families of soldiers who died in the Great War. Jack’s mother had matching watches made for herself and her daughter to commemorate Jack’s passing. Emily’s was destroyed in the fire that leveled the Halswell house in 1944. Eileen’s is still in the family.

Dear old Geb,

Just a few lines. I got your short note saying you had come out of the big scrap all right. I was so pleased… Since we came out of the trenches, we have been ‘touring’ on foot—with full packs, mind you—all over the country.

We are just about to go into the big battle that is raging over here. This will be the last letter I’ll be able to get away to you for some time. We are quite close to it now – the thunder of the big guns is tremendous and as I write this, I can see the flashes of the big ones. You may have seen a few big guns firing, but you will never see them in the countless numbers as we see them over here. It is simply gigantic and the rumble is huge….

Well, old chap, I trust to God to come out of this all right. You may depend we’ll give as good as we take, and better.

So, cheeroh old sport. I’ll write at the first opportunity. Best wishes to all the boys.

Your loving brother

Jack

In his handwritten Last Will and Testament, Jack left his share of the Callaghan estate to his mother, “if it was lawful,” and to his two brothers if not. He also left Gerald is gold watch and Huia his watch chain. On the back he wrote:

I have not mentioned my father or Eileen. Re Eileen, I have mentioned Ger and Huia because I think they need more of the world’s goods in order to make homes. I love Eileen no less than the others.

To my dear old father, as with mother, I leave for ever all the best love and thoughts possible.

Should fate cause you to read this, do so with pride, for I shall have given my life for a just and righteous cause and will have held up the honour of my good old grandfather’s name.

Jackie also left all his money in the Post Office Savings Bank to his fiancé, Christina.

A very small appreciation of this noble girl whom I would have married before I left NZ, but did not because I did not think it right or fair to her under the circumstances. I wish her to get a good pendant, like my mother's, with this money. The ring she has is also hers ("to do as she likes" is crossed out) for all time.

After nine months mourning, she would marry Alexander Gillanders on July 4, 1917. They had one son whom she named Duncan after her father and live until 1983, having reached the age of 91. Whether she kept the ring all that time is unknown.

The New Zealand government gave a small stipend to the families of soldiers who died in the Great War. Jack’s mother had matching watches made for herself and her daughter to commemorate Jack’s passing. Emily’s was destroyed in the fire that leveled the Halswell house in 1944. Eileen’s is still in the family.

In 1925, Jack’s parents funded a scholarship at Christchurch Boys’ High in his honor. The scholarship was still being awarded 100 years after is death. From the School Magazine of 1933:

The Jack Birdling Memorial Scholarship. This Scholarship, which was awarded in 1925 for the first time, has been founded by the parents of an Old Boy, Jack Birdling, who was killed in the Great War. The Scholarship, which is worth approximately ten pounds, is tenable for one year, but a scholar is not debarred from competing again. It is awarded on the results of an examination in prescribed portions of Imperial History, and all boys are eligible as competitors. The subject for this year is: The British in India.

A century after his death, the School still honours Jack Birdling, a man who would always ‘do the right thing.ʼ

Let us allow Jackie’s commanding officer, Major John Studhome, to have the last word (from the letter to Emily and Arthur):

I write these few lines to tell you how grieved I was to hear of your boy’s death; of all the many casualties in this war among our N.Z. officers there is no one that I regret so much as his. His was that happy sunny nature that springs from simple goodness of heart. He seemed always to do the right thing and avoid the wrong instinctively. He had not false shame or fear of being thought a humbug, which is so refreshing, but he simply went his own way and said what he thought as naturally as a child, and without being aware of it had a great influence for good wherever he was. He had such a cheery nature and his cheeriness was so contagious that he was a delightful man to work with. We had many a good laugh together.

His men simply loved him, though he was in every sense a good officer, and wouldn’t overlook bad work or slackness…

We cannot give you back your boy, but can only pray as I do that you may realise the greatness of the Cause he has died for, and that the happy memories he cannot but have left behind will lighten the sorrow and pain of his loss.

The Jack Birdling Memorial Scholarship. This Scholarship, which was awarded in 1925 for the first time, has been founded by the parents of an Old Boy, Jack Birdling, who was killed in the Great War. The Scholarship, which is worth approximately ten pounds, is tenable for one year, but a scholar is not debarred from competing again. It is awarded on the results of an examination in prescribed portions of Imperial History, and all boys are eligible as competitors. The subject for this year is: The British in India.

A century after his death, the School still honours Jack Birdling, a man who would always ‘do the right thing.ʼ

Let us allow Jackie’s commanding officer, Major John Studhome, to have the last word (from the letter to Emily and Arthur):

I write these few lines to tell you how grieved I was to hear of your boy’s death; of all the many casualties in this war among our N.Z. officers there is no one that I regret so much as his. His was that happy sunny nature that springs from simple goodness of heart. He seemed always to do the right thing and avoid the wrong instinctively. He had not false shame or fear of being thought a humbug, which is so refreshing, but he simply went his own way and said what he thought as naturally as a child, and without being aware of it had a great influence for good wherever he was. He had such a cheery nature and his cheeriness was so contagious that he was a delightful man to work with. We had many a good laugh together.

His men simply loved him, though he was in every sense a good officer, and wouldn’t overlook bad work or slackness…

We cannot give you back your boy, but can only pray as I do that you may realise the greatness of the Cause he has died for, and that the happy memories he cannot but have left behind will lighten the sorrow and pain of his loss.