Mary Ann Callaghan and John Burns

Birth: about 1837, Kilbreedy Minor, Limerick, Ireland

Death: 20 May 1901, Hectorville, South Australia

Burial: Adelaide, South Australia, Australia

Spouse: John Byrnes/Burns

Birth: about 1834, Limerick, Ireland

Death: 25 Jun 1906, Parkside (Asylum), South Australia

Father: Edmund Byrnes/Burns (1814-)

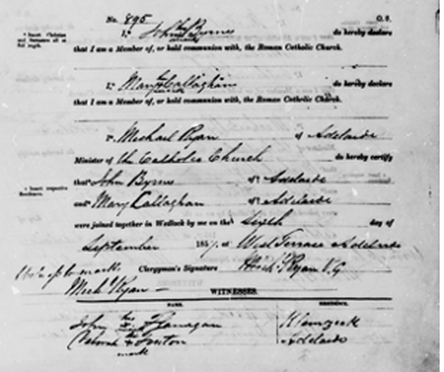

Marriage: 6 Sep 1857, St Patrick's Catholic Church, Adelaide, South Australia

Children: Edmund (1858-1859)

Honora May (1859-1922)

Michael (1861-1893)

John (1863-1941)

Edmund (1865-)

Ellen Agnes (1867-1921)

William (1869-1934)

James (1871 - )

Robert (~1872-)

Patrick (1873-1918)

Joseph John (1876-1956)

Mary Callaghan was born in 1837 (exact date unknown) in either Kilbreedy Minor or Effin, Limerick. She was the second child and eldest daughter of John Callaghan and Nora Carroll. She was likely named after her mother’s mother, but that is not known for certain.

In 1844, when Mary was seven, her family was evicted from the land on Lady Gertrude Fitzgerald’s estate where the family had lived and worked for four generations. As the oldest daughter, she would have had a front row view of the following year of threats, arrests, and outright fighting. At one point, a large number of her Carroll uncles and cousins showed up with pitch forks and threw rocks at the land agent and constables who tried to move the Callaghans. Finally, the family was pushed out of their home. They lived for a short time on a neighbor’s property in a mud hut. Then the Blight struck.

In the Autumn of 1845, a blight appeared unexpectedly among the potatoes. It was a black mold or fungus that caused much of the crop to rot in the fields, marking the beginning of the Great Famine (An Gorta Mor). The unique feature of the potato blight was the speed with which it spread. Eye witnesses said that a crop of potatoes in a field would be perfect in the morning time and by evening would be a rotting mess.

Four successive blighted harvests followed. Connacht and Munster were hit worst, where entire populations of towns had to abandon their homes and take to the road, searching for food. Bodies littered the countryside. Many died trying to eat weeds and any plants they could find, giving rise to a medical condition called “green mouth” from the stains. Many more died of typhus or dysentery. Between 1846 and 1849, over a million people died and another million emigrated, causing a population drop of almost 25 percent on the island. Mass graves appeared everywhere, and churches and towns could not properly update the death records. Little Mary would have seen people dying all around her daily.

The Callaghan family’s survival is due to their “people-in-law” the Carrolls, who took them in and gave them a home on land they rented behind the Effin Churchyard. It was a communal sort of living known as a clochán settlement, named after the beehive hut monastic settlements throughout the West Coast of Ireland. According to the article 10 Facts about Land Ownership (Ireland Reaching Out, July 2023),

Death: 20 May 1901, Hectorville, South Australia

Burial: Adelaide, South Australia, Australia

Spouse: John Byrnes/Burns

Birth: about 1834, Limerick, Ireland

Death: 25 Jun 1906, Parkside (Asylum), South Australia

Father: Edmund Byrnes/Burns (1814-)

Marriage: 6 Sep 1857, St Patrick's Catholic Church, Adelaide, South Australia

Children: Edmund (1858-1859)

Honora May (1859-1922)

Michael (1861-1893)

John (1863-1941)

Edmund (1865-)

Ellen Agnes (1867-1921)

William (1869-1934)

James (1871 - )

Robert (~1872-)

Patrick (1873-1918)

Joseph John (1876-1956)

Mary Callaghan was born in 1837 (exact date unknown) in either Kilbreedy Minor or Effin, Limerick. She was the second child and eldest daughter of John Callaghan and Nora Carroll. She was likely named after her mother’s mother, but that is not known for certain.

In 1844, when Mary was seven, her family was evicted from the land on Lady Gertrude Fitzgerald’s estate where the family had lived and worked for four generations. As the oldest daughter, she would have had a front row view of the following year of threats, arrests, and outright fighting. At one point, a large number of her Carroll uncles and cousins showed up with pitch forks and threw rocks at the land agent and constables who tried to move the Callaghans. Finally, the family was pushed out of their home. They lived for a short time on a neighbor’s property in a mud hut. Then the Blight struck.

In the Autumn of 1845, a blight appeared unexpectedly among the potatoes. It was a black mold or fungus that caused much of the crop to rot in the fields, marking the beginning of the Great Famine (An Gorta Mor). The unique feature of the potato blight was the speed with which it spread. Eye witnesses said that a crop of potatoes in a field would be perfect in the morning time and by evening would be a rotting mess.

Four successive blighted harvests followed. Connacht and Munster were hit worst, where entire populations of towns had to abandon their homes and take to the road, searching for food. Bodies littered the countryside. Many died trying to eat weeds and any plants they could find, giving rise to a medical condition called “green mouth” from the stains. Many more died of typhus or dysentery. Between 1846 and 1849, over a million people died and another million emigrated, causing a population drop of almost 25 percent on the island. Mass graves appeared everywhere, and churches and towns could not properly update the death records. Little Mary would have seen people dying all around her daily.

The Callaghan family’s survival is due to their “people-in-law” the Carrolls, who took them in and gave them a home on land they rented behind the Effin Churchyard. It was a communal sort of living known as a clochán settlement, named after the beehive hut monastic settlements throughout the West Coast of Ireland. According to the article 10 Facts about Land Ownership (Ireland Reaching Out, July 2023),

|

Traditionally, land was held in a cooperative-style settlement known as a clochán settlement. This meant that an area of land was occupied by several related families. They each farmed their own fields and certain fields were held in common with one another. Due to the penal laws, most Catholic families were unable to own land, but they often were able to create long leases or leases of multiple lives which allowed them to remain on land for several generations. This did not mean that they had sole rights over the land, as rent was still charged, but with a lease of three lives for example, a specific piece of land could be occupied for many years which gave some security to a family or several families.

https://www.irelandxo.com/ireland-xo/news/10-facts-about-land-ownership?utm_source=brevo&utm_campaign=10%20Facts%20about%20Land%20Ownership&utm_medium=email&utm_id=23 |

John Callaghan did not seem to have this kind of sibling support on the Fitzgerald lands, which had made him an easy target for eviction. The Callaghans would live among the Carrolls for the next twelve years.

In 1854, Mary’s older brother William went off to America where he initially settled in Illinois because he had a Carroll uncle who was a priest in Alton. The next year, when she turned 18, it was Mary’s turn to seek a new life. But she went the opposite direction. She boarded the ship South Sea with different Carroll relations: her uncle Patrick and his family, who were traveling under a government assistance program to bring laborers and servants to South Australia.

The ship South Sea was a 950 ton, rigged ship built in 1853 and commanded by Captain George Geere. Mary and the Carrolls likely boarded in late April at Cobh Harbor, Cork. The ship left Plymouth on May 2 and arrived at Port Adelaide on Monday, July 30, 1855—a journey of 90 days. It was the 25th ship of government passengers to South Australia that year. The trip was somewhat uneventful, but there were three births and four deaths by the time it was over. According to the South Australian Government Gazette (1855), the ship South Sea

Arrived from Plymouth on the 30th July, with 335 emigrants. She was commanded by Mr. George Geere, and Mr. James T. Fraser was the Surgeon-Superintendent. Three births and four deaths occurred before disembarkation. This ship had a cargo of iron, which strained the vessel and caused leakage, which produced dampness between decks. There were 124 single women by this ship, the majority of whom are not likely to find ready employment in this Colony. The discipline and management of the ship reflected credit on all in charge.

Luckily for Mary, they were wrong about employment, and she was able to land a job as a servant in Adelaide.

Maintaining a sense of identity through transition to a new life is difficult. In Being Irish: The Nineteenth Century South Australian Community of Baker’s Flat (Archaeologies vol 11 no 2 August 2015), Susann Arthure explored “Irishness” as a social identity and how it manifested in the archaeology of the Irish hamlet of Baker’s Flat near Kapunda in the mid-1800s. Here is a video of one ofArthure's lectures: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hpPf0LqvlKI.

Although the characteristics of a socially distinct identity like Irishness depend on the point of view, Arthure found several characteristics common to Irishness. The most common and important issue was that Irishness is “not English.” That might be the only thing the Irish and English agree upon. The Anglo-Irish were not even considered to be English by the English—they had “gone native.” And even after 700 years, the Irish still considered them English.

More distinct characteristics as to what Irishness IS would be: 1) the centrality of religion (particularly Roman Catholicism) to daily life, 2) a “degree of wildness, whimsy, and myth,” 3) a certain uncontrollable lawlessness, and 4) the establishment of alliances with other Irish people. This last is interesting in light of the characterization of the Irish in Ireland as quarrelsome and competitive amongst themselves.

In That Beloved Country, That No Place Else Resembles: Connotations of Irishness in Irish-Australasian Letters, 1841-1915 (Fitzgerald, 1991), David Fitzgerald did a content analysis of 159 letters to and from people in Ireland and in Australia. He found a strong sense of duty and obligation (not at all uncommon among other immigrant groups) but which was contrasted with a sense of irreverence. He also found a strong sense of national pride that was strangely devoid of nationalism on the part of the immigrants. There seems to have been less interest in the Home Rule Movement abroad than one would have expected.

In terms of the archaeology, Baker’s Flat exhibits a classic clochán settlement with a rundale field system. The rundale system (apparently from the Irish Gaelic words "Roinn" which refers to the division of something and "Dáil", usually meaning meeting or assembly) was a form of occupation of land in Ireland that dated to the early Medieval period. The land is divided into discontinuous plots, and cultivated and occupied by a number of tenants to whom it is leased jointly. This was an attempt to ensure that each tenant had access to an equal share of the quality land in a place where quality land was in short supply. This is very similar to how the land was divided by the Carrolls in Effin.

The randomness of the field delineations—as perceived by outsiders—was a distinctly Irish characteristic. The main clochán area, where the small thatched cottages were concentrated, was situated in a cluster on the best land which was surrounded by mountain or grazing land of inferior quality where the livestock was grazed during summer or dry periods. This practice was known as booleying (or transhumance). All the sheep or cattle of the village were grazed together to alleviate pressure on growing crops and also provided fresh pasture for livestock. In the remote western areas of Ireland where the rundale system was most commonly seen, the land was a complex mixture of arable, rough, and bog land. It was an Irish defiance of English custom hiding in plain sight.

To quote Arthure’s conclusion,

Social identity, and its alignment to co-operative behavior and characteristics, is particularly important in this study. The Irish, by choice or circumstance, built a settlement that was physically and socially separate from the broader Kapunda community, which allowed for the development of a distinctive identity. They acted in the context of a complex set of social relations that meant they were identified by the dominant power as Irish, but a particular form of unskilled, uncontrollable Irish familiar and acceptable to the prevailing views of that time. Their value was in the labor they could provide for the local elite, for example, in the mines, and there was a clear boundary between Baker’s Flat and the broader community. Following McGuire (1982), that new migrant groups retain their ethnicity by maintaining strong boundaries, the historical and archaeological evidence of the Baker’s Flat settlement shows how the occupants retained their Irishness by constructing houses using a familiar vernacular architecture and practicing their Catholic faith. They also adhered to some degree of respectability in their personal lives by going to work, wearing fashionable jewelry and registering their dogs, which had the dual advantages of conforming to Victorian values and promoting community cohesion.

The power relationships between Baker’s Flat and the broader community are perhaps most obvious in the decade-long Forster et al. v. Fisher court case, which highlighted the power of collective action against the landowners. The adoption of a traditional Irish settlement and farming system can be seen as a subtle act of defiance of the dominant Anglo power by successfully retaining a cultural practice, an Irishness hidden in plain view, as it were. This system is also the most visible, least ‘respectable’ and least conforming part of the community, in which the rural setting may be key; whilst there are advantages in conforming to some of the personal ideals of respectability, for these new settlers in a new land there is also value in adhering to traditional country lifeways that have proved successful in the past. This clachan and rundale system, perceived by outsiders as chaotic, would have facilitated the simple labeling by the dominant power of the Baker’s Flat people as the stereotypical ‘dirty Irish’. The archaeology at Baker’s Flat proposes a more complete story than this accepted narrative, with evidence of a tightly knit community trying to lead respectable lives at a personal level, whilst remaining adept at manipulating the local authorities and landscape to suit their needs.

These were the adjustments being made by the Irish at the time Mary began her new life Australia. Somewhere in the next two years, she met John Burns.

In 1854, Mary’s older brother William went off to America where he initially settled in Illinois because he had a Carroll uncle who was a priest in Alton. The next year, when she turned 18, it was Mary’s turn to seek a new life. But she went the opposite direction. She boarded the ship South Sea with different Carroll relations: her uncle Patrick and his family, who were traveling under a government assistance program to bring laborers and servants to South Australia.

The ship South Sea was a 950 ton, rigged ship built in 1853 and commanded by Captain George Geere. Mary and the Carrolls likely boarded in late April at Cobh Harbor, Cork. The ship left Plymouth on May 2 and arrived at Port Adelaide on Monday, July 30, 1855—a journey of 90 days. It was the 25th ship of government passengers to South Australia that year. The trip was somewhat uneventful, but there were three births and four deaths by the time it was over. According to the South Australian Government Gazette (1855), the ship South Sea

Arrived from Plymouth on the 30th July, with 335 emigrants. She was commanded by Mr. George Geere, and Mr. James T. Fraser was the Surgeon-Superintendent. Three births and four deaths occurred before disembarkation. This ship had a cargo of iron, which strained the vessel and caused leakage, which produced dampness between decks. There were 124 single women by this ship, the majority of whom are not likely to find ready employment in this Colony. The discipline and management of the ship reflected credit on all in charge.

Luckily for Mary, they were wrong about employment, and she was able to land a job as a servant in Adelaide.

Maintaining a sense of identity through transition to a new life is difficult. In Being Irish: The Nineteenth Century South Australian Community of Baker’s Flat (Archaeologies vol 11 no 2 August 2015), Susann Arthure explored “Irishness” as a social identity and how it manifested in the archaeology of the Irish hamlet of Baker’s Flat near Kapunda in the mid-1800s. Here is a video of one ofArthure's lectures: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hpPf0LqvlKI.

Although the characteristics of a socially distinct identity like Irishness depend on the point of view, Arthure found several characteristics common to Irishness. The most common and important issue was that Irishness is “not English.” That might be the only thing the Irish and English agree upon. The Anglo-Irish were not even considered to be English by the English—they had “gone native.” And even after 700 years, the Irish still considered them English.

More distinct characteristics as to what Irishness IS would be: 1) the centrality of religion (particularly Roman Catholicism) to daily life, 2) a “degree of wildness, whimsy, and myth,” 3) a certain uncontrollable lawlessness, and 4) the establishment of alliances with other Irish people. This last is interesting in light of the characterization of the Irish in Ireland as quarrelsome and competitive amongst themselves.

In That Beloved Country, That No Place Else Resembles: Connotations of Irishness in Irish-Australasian Letters, 1841-1915 (Fitzgerald, 1991), David Fitzgerald did a content analysis of 159 letters to and from people in Ireland and in Australia. He found a strong sense of duty and obligation (not at all uncommon among other immigrant groups) but which was contrasted with a sense of irreverence. He also found a strong sense of national pride that was strangely devoid of nationalism on the part of the immigrants. There seems to have been less interest in the Home Rule Movement abroad than one would have expected.

In terms of the archaeology, Baker’s Flat exhibits a classic clochán settlement with a rundale field system. The rundale system (apparently from the Irish Gaelic words "Roinn" which refers to the division of something and "Dáil", usually meaning meeting or assembly) was a form of occupation of land in Ireland that dated to the early Medieval period. The land is divided into discontinuous plots, and cultivated and occupied by a number of tenants to whom it is leased jointly. This was an attempt to ensure that each tenant had access to an equal share of the quality land in a place where quality land was in short supply. This is very similar to how the land was divided by the Carrolls in Effin.

The randomness of the field delineations—as perceived by outsiders—was a distinctly Irish characteristic. The main clochán area, where the small thatched cottages were concentrated, was situated in a cluster on the best land which was surrounded by mountain or grazing land of inferior quality where the livestock was grazed during summer or dry periods. This practice was known as booleying (or transhumance). All the sheep or cattle of the village were grazed together to alleviate pressure on growing crops and also provided fresh pasture for livestock. In the remote western areas of Ireland where the rundale system was most commonly seen, the land was a complex mixture of arable, rough, and bog land. It was an Irish defiance of English custom hiding in plain sight.

To quote Arthure’s conclusion,

Social identity, and its alignment to co-operative behavior and characteristics, is particularly important in this study. The Irish, by choice or circumstance, built a settlement that was physically and socially separate from the broader Kapunda community, which allowed for the development of a distinctive identity. They acted in the context of a complex set of social relations that meant they were identified by the dominant power as Irish, but a particular form of unskilled, uncontrollable Irish familiar and acceptable to the prevailing views of that time. Their value was in the labor they could provide for the local elite, for example, in the mines, and there was a clear boundary between Baker’s Flat and the broader community. Following McGuire (1982), that new migrant groups retain their ethnicity by maintaining strong boundaries, the historical and archaeological evidence of the Baker’s Flat settlement shows how the occupants retained their Irishness by constructing houses using a familiar vernacular architecture and practicing their Catholic faith. They also adhered to some degree of respectability in their personal lives by going to work, wearing fashionable jewelry and registering their dogs, which had the dual advantages of conforming to Victorian values and promoting community cohesion.

The power relationships between Baker’s Flat and the broader community are perhaps most obvious in the decade-long Forster et al. v. Fisher court case, which highlighted the power of collective action against the landowners. The adoption of a traditional Irish settlement and farming system can be seen as a subtle act of defiance of the dominant Anglo power by successfully retaining a cultural practice, an Irishness hidden in plain view, as it were. This system is also the most visible, least ‘respectable’ and least conforming part of the community, in which the rural setting may be key; whilst there are advantages in conforming to some of the personal ideals of respectability, for these new settlers in a new land there is also value in adhering to traditional country lifeways that have proved successful in the past. This clachan and rundale system, perceived by outsiders as chaotic, would have facilitated the simple labeling by the dominant power of the Baker’s Flat people as the stereotypical ‘dirty Irish’. The archaeology at Baker’s Flat proposes a more complete story than this accepted narrative, with evidence of a tightly knit community trying to lead respectable lives at a personal level, whilst remaining adept at manipulating the local authorities and landscape to suit their needs.

These were the adjustments being made by the Irish at the time Mary began her new life Australia. Somewhere in the next two years, she met John Burns.

John Byrnes (or Burns, as the spelling would evolve) was the son on Edmund and Ellen Byrnes. Little is known for sure about his early life. According to his sister Ellen Kirby’s 1913 obituary, they were born in Charleville, Co Limerick…but Charleville is in Cork, not Limerick. (The Callaghans sometimes listed Charleville or Cork as their home in later obituaries since Charleville is the closest large town to Effin.) It is unknown if Ellen was his only sibling. There were a half-dozen land records for an Edmund Byrnes in Limerick, but they are mostly in the north near Adare. His mother’s obituary indicates that they came to South Australia around 1857, but that is an estimate and likely a little late. A ship’s passenger record for the Byrnes has not been found yet.

John and Mary were married on September 6, 1857, at St. Patrick’s Church in Adelaide by Fr. Michael Ryan. John was 23, and Mary was 21. Their witnesses were John Flanagan and Deborah Fenton. All four signed the marriage license with a mark, indicating none could write. The young couple settled somewhere in Campbelltown, a nine-square mile area northeast of Port Adelaide. Where exactly is unsure, but the first record of John Burns in Hectorville in 1858 (Reference Memorial 2/144).

The rest of Mary’s family arrived from Ireland on the Bee in October 11, 1858.She was nine months pregnant at the time and having the family there would have been a mixed blessing.Having her sisters there to help her through the final days of the pregnancy and the recovery would have been a godsend.On the other hand, having eight guests staying at the house at such a time would have strained all civility.

Mary gave birth to her and John’s first son, Edmund, on October 18, 1858. He was named after his paternal grandfather, who seems to have died in Ireland before the family came to South Australia. Edmund was baptized in Adelaide by Fr. Michael Ryan on October 18, 1858 and his godparents were Mary's brother Patrick and John's sister Ellen. Unfortunately, Young Edmund only survived four months and died on February 5, 1859.

A second child, a daughter named Hanora after Mary’s mother, was born on November 25, 1859, in Hectorville. Nora was baptized in Adelaide by Fr. John Smyth on November 27, 1859, and his godparents were Mary's brother Michael and a woman named Ellen Guppy. There would be ten Burns children in total—though, two (Edmund b. 1865 and Robert) are only known through family tradition and have not been confirmed with documentation. Most (possibly all) were born in Hectorville.

John and Mary were married on September 6, 1857, at St. Patrick’s Church in Adelaide by Fr. Michael Ryan. John was 23, and Mary was 21. Their witnesses were John Flanagan and Deborah Fenton. All four signed the marriage license with a mark, indicating none could write. The young couple settled somewhere in Campbelltown, a nine-square mile area northeast of Port Adelaide. Where exactly is unsure, but the first record of John Burns in Hectorville in 1858 (Reference Memorial 2/144).

The rest of Mary’s family arrived from Ireland on the Bee in October 11, 1858.She was nine months pregnant at the time and having the family there would have been a mixed blessing.Having her sisters there to help her through the final days of the pregnancy and the recovery would have been a godsend.On the other hand, having eight guests staying at the house at such a time would have strained all civility.

Mary gave birth to her and John’s first son, Edmund, on October 18, 1858. He was named after his paternal grandfather, who seems to have died in Ireland before the family came to South Australia. Edmund was baptized in Adelaide by Fr. Michael Ryan on October 18, 1858 and his godparents were Mary's brother Patrick and John's sister Ellen. Unfortunately, Young Edmund only survived four months and died on February 5, 1859.

A second child, a daughter named Hanora after Mary’s mother, was born on November 25, 1859, in Hectorville. Nora was baptized in Adelaide by Fr. John Smyth on November 27, 1859, and his godparents were Mary's brother Michael and a woman named Ellen Guppy. There would be ten Burns children in total—though, two (Edmund b. 1865 and Robert) are only known through family tradition and have not been confirmed with documentation. Most (possibly all) were born in Hectorville.

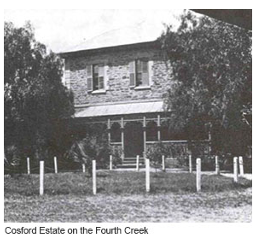

Hectorville, a small suburb of the City of Campbelltown, was a 134-acre section named after John Hector, the attorney who purchased the investment for Miss Jane Botting of Worthing, Sussex, in about 1839. In 1849, the first house in town was built at Fourth Creek. The Price Maurice House was initially called Fourth Creek, but it later became known as the Cosford Estate.

The 1857/58 rate list shows a half dozen or so earthen huts occupied by Irish laborers named Barry, Gallagher, Cunningham, Fenton (possibly, the father of Mary’s maid-of-honor), Flavel, O’Brien, and Yeates.It seemed to be on its way to being a clochán settlement like Baker’s Flat, but without a local mine to draw a larger population. After leasing the lots (probably for only a pound per acre), Miss Botting sold the land for £3000 to Patrick Boyce Coglin, an Irish Catholic immigrant from Tasmania. Coglin, who had apprenticed as an architect and builder in Tasmania, designed the unusual layout of the town of a rectangle within a rectangle with a diagonal street bisecting the town. Unfortunately, he missed the opportunity to put in a town square or a commons for the people to gather.

The 1857/58 rate list shows a half dozen or so earthen huts occupied by Irish laborers named Barry, Gallagher, Cunningham, Fenton (possibly, the father of Mary’s maid-of-honor), Flavel, O’Brien, and Yeates.It seemed to be on its way to being a clochán settlement like Baker’s Flat, but without a local mine to draw a larger population. After leasing the lots (probably for only a pound per acre), Miss Botting sold the land for £3000 to Patrick Boyce Coglin, an Irish Catholic immigrant from Tasmania. Coglin, who had apprenticed as an architect and builder in Tasmania, designed the unusual layout of the town of a rectangle within a rectangle with a diagonal street bisecting the town. Unfortunately, he missed the opportunity to put in a town square or a commons for the people to gather.

According to From the River to the Hills: Campbelltown (Walburton, 1986):

Coglin’s most enduring legacy was demographic. Many of his sales were made to Irish labourers, probably encouraged by him to become landowners, and perhaps financed by him—although plenty of credit sources were available, including the East Torrens Building Society and the Loyal Newton Lodge of the Independent Order of Oddfellows (IOOF). Encouragement and pointing in the right direction were probably his main aid to immigrants. In return, Hectorville became a strong centre for his religion, where its first Roman Catholic Church (and weekday school) was built in 1863…

Coglin’s most enduring legacy was demographic. Many of his sales were made to Irish labourers, probably encouraged by him to become landowners, and perhaps financed by him—although plenty of credit sources were available, including the East Torrens Building Society and the Loyal Newton Lodge of the Independent Order of Oddfellows (IOOF). Encouragement and pointing in the right direction were probably his main aid to immigrants. In return, Hectorville became a strong centre for his religion, where its first Roman Catholic Church (and weekday school) was built in 1863…

The Church of the Annunciation was the first Roman Catholic church built in the eastern suburbs of Adelaide. According to John Taggart Leaney’s Campbelltown 1868 – 1968 (1968):

Catholicity in Campbelltown had its beginning in a little church built on a small piece of land on North Street in the village of Hectorville, southeast of a major intersection, where five roads meet, now known as Glynde corner. The church, which still stands, had the distinction of being the first Catholic church built in the area then beginning to develop to the east of Adelaide.

Its opening date, 2nd July, 1863, was an important occasion. Over 200 people were assembled to take part in the ceremony. Those officiating were the Reverend Fathers J. Smyth, Reynolds, Russell, and Byrne. Up to this time, the members of the Church had assembled once every month for mass at the house of Mrs. Fox at Maybank, Athelstone.

The church building was also used for the school during the week days and was conducted by an efficient master until about 1970 when the sisters of the Congregation of the Sisters of St. Joseph, a religious group, were appointed to teach in this school. The founder of this order, Reverend Mother Mary McKillop, knew of this little religious teaching center.

The Church of the Annunciation would be at the heart of the Hectorville community for the next century, and the Burns family was an active part of it. In 1917, the second, larger church building was erected and the old building became the school full time. A third, modern and spacious building was consecrated on May 25, 1863, six weeks shy of the centennial of the original.

Catholicity in Campbelltown had its beginning in a little church built on a small piece of land on North Street in the village of Hectorville, southeast of a major intersection, where five roads meet, now known as Glynde corner. The church, which still stands, had the distinction of being the first Catholic church built in the area then beginning to develop to the east of Adelaide.

Its opening date, 2nd July, 1863, was an important occasion. Over 200 people were assembled to take part in the ceremony. Those officiating were the Reverend Fathers J. Smyth, Reynolds, Russell, and Byrne. Up to this time, the members of the Church had assembled once every month for mass at the house of Mrs. Fox at Maybank, Athelstone.

The church building was also used for the school during the week days and was conducted by an efficient master until about 1970 when the sisters of the Congregation of the Sisters of St. Joseph, a religious group, were appointed to teach in this school. The founder of this order, Reverend Mother Mary McKillop, knew of this little religious teaching center.

The Church of the Annunciation would be at the heart of the Hectorville community for the next century, and the Burns family was an active part of it. In 1917, the second, larger church building was erected and the old building became the school full time. A third, modern and spacious building was consecrated on May 25, 1863, six weeks shy of the centennial of the original.

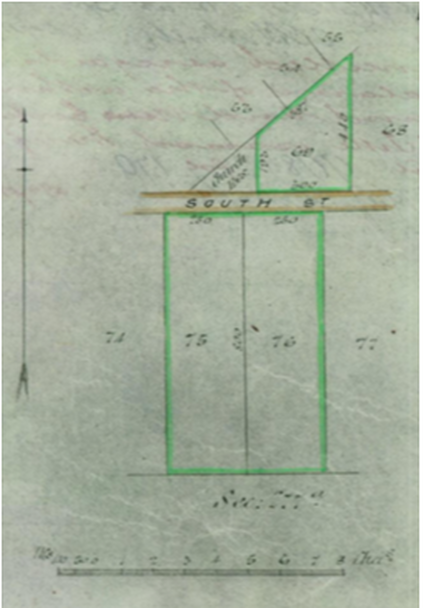

Mary Callaghan’s husband became one of those new landowners. It was believed in the family that he purchased allotments 51-53 on Hectorville road. As can be seen on the plot map above, it was originally intended for a Protestant Church. According to Walburton (1986), John also bought lot 28 on the Glynburn Road in 1866 where he opened a market garden, which he operated for 30 years before selling it to James Benjamin Pierson. This turns out to be incorrect, though. The lots that ended up in the hands of the Piersons were the lots owned by John’s father-in-law John Callaghan. John Burns actually purchased Allotments 69, 75 and 76. (His son Joseph inherited them and sold the land in 1912.) This amounted to 12.5 acres and included a pisé house of two rooms.

According to The Kalgoolie Miner (7 Oct 1949):

In many parts of Australia stand old houses whose owners imagine them to be built of stone. Unless they had reason to remove the outer surface, they would never suspect that the walls are in fact built of the very earth on which they stand.

‘Pisé de terre,’ generally abbreviated to ‘pisé’ is the French name for rammed earth. Records, experiments, and the evidence of buildings still standing all over the world show that rammed earth is an excellent and durable material for building houses.

It is no new-fangled invention called forth by the post-war shortage of building materials. It has been proved by nearly 2000 years of use. Pliny gives an account of pisé building in his 'Natural History.' It has been practiced for centuries in the French province of Lyons. It has been revived and forgotten again several times in the history of building. The last revival was in England after World War I., when scientific experiments and an experimental country house built of pisé proved its complete efficiency as a building material.

Pisé houses should not be confused with mud. It is essentially a 'dry earth' method of construction. The earth is rammed hard, a layer at a time, between fixed retaining boards, or ‘shuttering,’ and in a short time acquires the hardness of stone. The method is described fully in 'Cottage Building in Cob, Pisé, Chalk and Clay,' written by Clough Williams Ellis and published in 1920.

https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/95643954

A two-room house—no matter how sturdy—would have been a tight fit for two parents with ten children.

Market gardening was and is small-scale farming larger than a home garden, but small enough that many of the principles of gardening are applicable. Unlike large, industrial farms, which practice monoculture and mechanization, many different crops and varieties are grown in market gardens, and more manual labor is needed when gardening techniques are used. It is unknown what crops the Burnses and Callaghans grew, but the Piersons grew celery and cauliflower.

Despite the good soil and the creek and a pubic well, Hectorville had a problem. There was not enough water for the inhabitants, let alone all the farming. All 27 families living in Hectorville signed a petition to Parliament in 1875. The water main to the City from the reservoir was only a few yards outside of town, but no reservoir water was piped directly into Hectorville. According to an article in the Lantern (1876):

The people living in the modest little village of Hectorville are suffering from an intolerable grievance. They are very short of water, in fact they have not enough for the most ordinary domestic purposes and what they have is of bad quality. The main from the Reservoir passes within a very short distance of the village, and the people there are very anxious to have a pipe led into the village. They are willing to pay the expense. But no. The Waterworks authorities are obdurate. The law has not provided for it, and so they must go without; and they have to go without, except to the extent that the charity of the keeper of the standpipe on the Payneham Road can be worked upon.

During the warm weather, children may be seen begging for water, and dragging it down to their house in buckets; and when the standpipe is not accessible, the little ones are driven actually to dip the water out of the horse trough in order to enable their parents to have the most common supply of this greatest necessity of life…

Water service was not completely extended to Hectorville until 1897.

John was in the newspapers a few times over the years. Besides market gardening, John also did some contracting work for the town, cleaning scrub brush from land on the Clousthal Road, hauling metal, building his own house. In 1879, John served as a District Constable for Campbelltown for a year. In 1897, he was listed as a signer of the petition that finally granted the extension of the water main to Hectorville. His son Joseph would serve in the same capacity in 1905-06. Clearly, the Burnses were well respected in the community.

Other than her death notice, Mary only appears in the newspapers once. In the South Australian Register (Adelaide, SA: 1839 - 1900), this article appeared in 1878:

Mary Burns, married woman, was charged with using insulting language to Mary Gallagher, married woman, on the Hectorville Road, on February 27. Mr. Harold Downer for the defendant. There was a cross-information. Fined 5s. each.

Like her brother Patrick in New Zealand, Mary seems to have had trouble with neighbors. Since they both received fines, future insults seem to have been kept private.

The next generation of the Burns branch of the family began on December 9, 1880, with the birth of John Thomas Quinlan to Mary and John’s daughter Nora. He would be the first of 33 grandchildren. Mary was still in her mid-forties, and John Thomas was only four years younger than his youngest uncle Joseph. Eleven of the 33 grandchildren were born after Mary’s death.

The 1880s were a boomtime for the Australian economy. While much of the rest of the world suffered what was known as the Long Depression (at the time it was called the Great Depression, but the 1930s economic disaster took that title over later), Australia was experiencing a property bubble and building boom. But bust follows boom. According to the Reserve Bank of Australia:

The depression, which saw real GDP fall 17 per cent over 1892 and 1893, and the accompanying financial crisis, which reached a peak in 1893, were the most severe in Australia's history. The overextension of the 1880s property boom and its unravelling led to an abrupt collapse of private investment in the pastoral industry and urban development and a sharp pullback in public infrastructure investment. A fall-off in capital inflow from Britain, adverse movements in the terms of trade, and drought in 1895 accentuated and prolonged the depression.

https://www.rba.gov.au/publications/rdp/2001/2001-07/1890s-depression.html

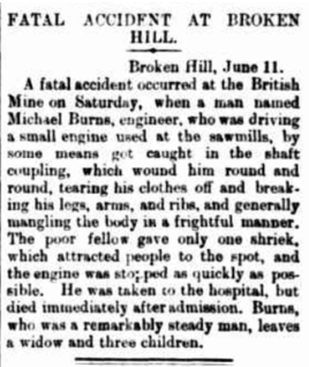

By the 1890s, the older generation began to pass on. In 1890, Mary’s father John Callaghan died at the age of 74. Two years later, John’s mother Ellen passed away in Gawler at the age of 85 in the home of her daughter Ellen Kirby. More distressing was the loss of their 32-year-old son Michael in a mine accident in 1893:

According to The Kalgoolie Miner (7 Oct 1949):

In many parts of Australia stand old houses whose owners imagine them to be built of stone. Unless they had reason to remove the outer surface, they would never suspect that the walls are in fact built of the very earth on which they stand.

‘Pisé de terre,’ generally abbreviated to ‘pisé’ is the French name for rammed earth. Records, experiments, and the evidence of buildings still standing all over the world show that rammed earth is an excellent and durable material for building houses.

It is no new-fangled invention called forth by the post-war shortage of building materials. It has been proved by nearly 2000 years of use. Pliny gives an account of pisé building in his 'Natural History.' It has been practiced for centuries in the French province of Lyons. It has been revived and forgotten again several times in the history of building. The last revival was in England after World War I., when scientific experiments and an experimental country house built of pisé proved its complete efficiency as a building material.

Pisé houses should not be confused with mud. It is essentially a 'dry earth' method of construction. The earth is rammed hard, a layer at a time, between fixed retaining boards, or ‘shuttering,’ and in a short time acquires the hardness of stone. The method is described fully in 'Cottage Building in Cob, Pisé, Chalk and Clay,' written by Clough Williams Ellis and published in 1920.

https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/95643954

A two-room house—no matter how sturdy—would have been a tight fit for two parents with ten children.

Market gardening was and is small-scale farming larger than a home garden, but small enough that many of the principles of gardening are applicable. Unlike large, industrial farms, which practice monoculture and mechanization, many different crops and varieties are grown in market gardens, and more manual labor is needed when gardening techniques are used. It is unknown what crops the Burnses and Callaghans grew, but the Piersons grew celery and cauliflower.

Despite the good soil and the creek and a pubic well, Hectorville had a problem. There was not enough water for the inhabitants, let alone all the farming. All 27 families living in Hectorville signed a petition to Parliament in 1875. The water main to the City from the reservoir was only a few yards outside of town, but no reservoir water was piped directly into Hectorville. According to an article in the Lantern (1876):

The people living in the modest little village of Hectorville are suffering from an intolerable grievance. They are very short of water, in fact they have not enough for the most ordinary domestic purposes and what they have is of bad quality. The main from the Reservoir passes within a very short distance of the village, and the people there are very anxious to have a pipe led into the village. They are willing to pay the expense. But no. The Waterworks authorities are obdurate. The law has not provided for it, and so they must go without; and they have to go without, except to the extent that the charity of the keeper of the standpipe on the Payneham Road can be worked upon.

During the warm weather, children may be seen begging for water, and dragging it down to their house in buckets; and when the standpipe is not accessible, the little ones are driven actually to dip the water out of the horse trough in order to enable their parents to have the most common supply of this greatest necessity of life…

Water service was not completely extended to Hectorville until 1897.

John was in the newspapers a few times over the years. Besides market gardening, John also did some contracting work for the town, cleaning scrub brush from land on the Clousthal Road, hauling metal, building his own house. In 1879, John served as a District Constable for Campbelltown for a year. In 1897, he was listed as a signer of the petition that finally granted the extension of the water main to Hectorville. His son Joseph would serve in the same capacity in 1905-06. Clearly, the Burnses were well respected in the community.

Other than her death notice, Mary only appears in the newspapers once. In the South Australian Register (Adelaide, SA: 1839 - 1900), this article appeared in 1878:

Mary Burns, married woman, was charged with using insulting language to Mary Gallagher, married woman, on the Hectorville Road, on February 27. Mr. Harold Downer for the defendant. There was a cross-information. Fined 5s. each.

Like her brother Patrick in New Zealand, Mary seems to have had trouble with neighbors. Since they both received fines, future insults seem to have been kept private.

The next generation of the Burns branch of the family began on December 9, 1880, with the birth of John Thomas Quinlan to Mary and John’s daughter Nora. He would be the first of 33 grandchildren. Mary was still in her mid-forties, and John Thomas was only four years younger than his youngest uncle Joseph. Eleven of the 33 grandchildren were born after Mary’s death.

The 1880s were a boomtime for the Australian economy. While much of the rest of the world suffered what was known as the Long Depression (at the time it was called the Great Depression, but the 1930s economic disaster took that title over later), Australia was experiencing a property bubble and building boom. But bust follows boom. According to the Reserve Bank of Australia:

The depression, which saw real GDP fall 17 per cent over 1892 and 1893, and the accompanying financial crisis, which reached a peak in 1893, were the most severe in Australia's history. The overextension of the 1880s property boom and its unravelling led to an abrupt collapse of private investment in the pastoral industry and urban development and a sharp pullback in public infrastructure investment. A fall-off in capital inflow from Britain, adverse movements in the terms of trade, and drought in 1895 accentuated and prolonged the depression.

https://www.rba.gov.au/publications/rdp/2001/2001-07/1890s-depression.html

By the 1890s, the older generation began to pass on. In 1890, Mary’s father John Callaghan died at the age of 74. Two years later, John’s mother Ellen passed away in Gawler at the age of 85 in the home of her daughter Ellen Kirby. More distressing was the loss of their 32-year-old son Michael in a mine accident in 1893:

FATAL ACCIDENT AT BROKEN HILL.

Broken Hill. June 11.

A fatal accident occurred at the British Mine on Saturday, when a man named Michael Burns, engineer, who was driving a small engine used at the sawmills, by some means got caught in the shaft coupling, which wound him round and round, tearing his clothes off and breaking his legs, arms, and ribs, and generally mangling the body in a frightful manner, the poor fellow gave only one shriek, which attracted people to the spot, and the engine was stopped as quickly as possible. He was taken to the hospital, but died immediately after admission. Burns, who was a remarkably steady man, leaves a widow and three children.

In 1896, Mary’s father’s second wife, Mary Anne Cleary Callaghan also died.

Broken Hill. June 11.

A fatal accident occurred at the British Mine on Saturday, when a man named Michael Burns, engineer, who was driving a small engine used at the sawmills, by some means got caught in the shaft coupling, which wound him round and round, tearing his clothes off and breaking his legs, arms, and ribs, and generally mangling the body in a frightful manner, the poor fellow gave only one shriek, which attracted people to the spot, and the engine was stopped as quickly as possible. He was taken to the hospital, but died immediately after admission. Burns, who was a remarkably steady man, leaves a widow and three children.

In 1896, Mary’s father’s second wife, Mary Anne Cleary Callaghan also died.

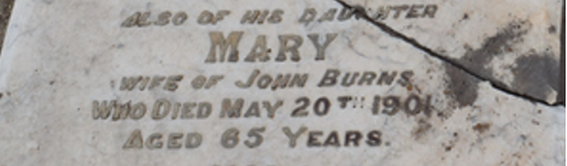

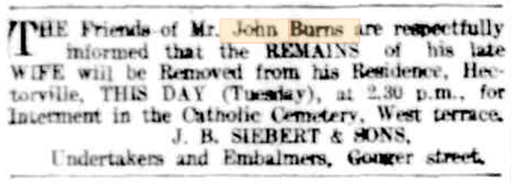

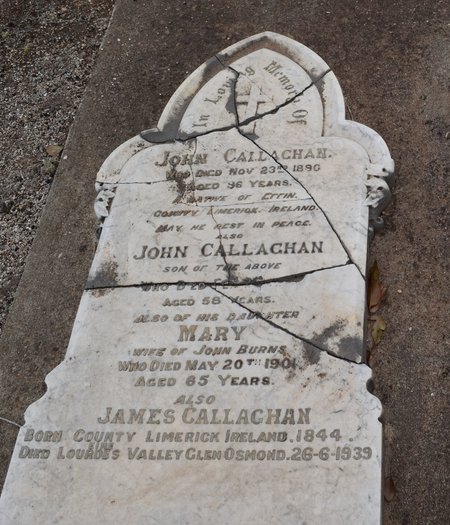

Mary Callaghan Burns herself passed away on May 20, 1901, at her home in Hectorville. She was 65 years old. Her brother had preceded her in death in the same house just three months before. She was interred with her father and brother—but not her husband—in the West Terrace Catholic Cemetery.

John Burns’ son Joseph had to have John committed to the Adelaide Asylum at Parkside, South Australia, in February of 1905. He was suffering from “cerebral disease and senile decay.” He was in the hospital ward confined to his bed for 16 months because he was “very helpless and stupid and everything had to be done for him.”

John Burns’ son Joseph had to have John committed to the Adelaide Asylum at Parkside, South Australia, in February of 1905. He was suffering from “cerebral disease and senile decay.” He was in the hospital ward confined to his bed for 16 months because he was “very helpless and stupid and everything had to be done for him.”

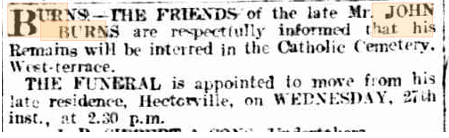

-John died on June 25, 1906, having survived his wife by five years. After an Irish wake in his home, he was laid to rest near his wife and in-laws at in the West Terrace Catholic Cemetery.

Mary Callaghan and John Burns lived lives of wide=ranging circumstances. They grew up in a land ruled by famine and desperation, then traveled half way around the world to another hemisphere to find love and a new home in a land of prosperity and possibilities. She went from a child of eviction to a respected member of the community; he went from a childhood of need to being a landowner, successful businessman, and a county constable. They were good Catholics who were married for 45 years and had ten children and 33 grandchildren. They are the giants on which their descendants stand.

Mary Callaghan and John Burns lived lives of wide=ranging circumstances. They grew up in a land ruled by famine and desperation, then traveled half way around the world to another hemisphere to find love and a new home in a land of prosperity and possibilities. She went from a child of eviction to a respected member of the community; he went from a childhood of need to being a landowner, successful businessman, and a county constable. They were good Catholics who were married for 45 years and had ten children and 33 grandchildren. They are the giants on which their descendants stand.