Patrick Callaghan and Emma Ware

No photos available

Birth: 17 Mar 1840 or 1841, Kilbreedy Minor, Mount Blakeny, Limerick, Ireland

Death: 28 Jul 1907, Christchurch City, Canterbury, New Zealand

Burial: 1907, Linwood, Christchurch City, Canterbury, New Zealand

Spouse: Emma Ware

Birth: 2 Aug 1846, Chulmleigh, Devonshire, England

Death: 30 Nov 1920, Christchurch, Canterbury, New Zealand

Marriage: 1867, New Zealand

Children: Emily Agnes (1868-1943)

Death: 28 Jul 1907, Christchurch City, Canterbury, New Zealand

Burial: 1907, Linwood, Christchurch City, Canterbury, New Zealand

Spouse: Emma Ware

Birth: 2 Aug 1846, Chulmleigh, Devonshire, England

Death: 30 Nov 1920, Christchurch, Canterbury, New Zealand

Marriage: 1867, New Zealand

Children: Emily Agnes (1868-1943)

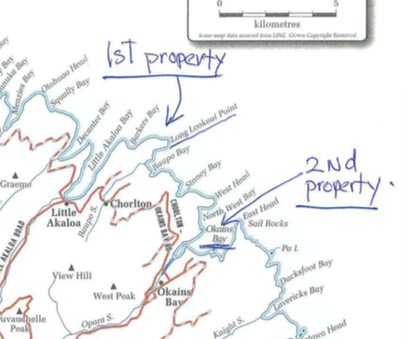

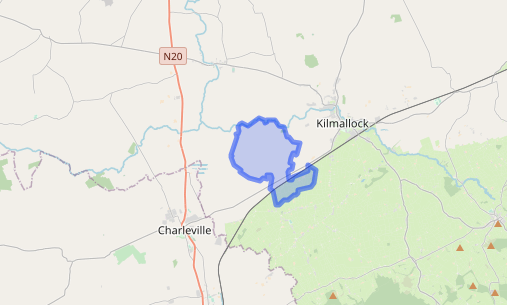

Patrick Callaghan was born on St. Patrick’s Day, either 1840 or 1841, depending on the records. He was the fifth child and third son on John Callaghan and Nora Carroll. By family naming tradition, he should have been John, after his father, but the great saint took precedent, and his next brother became John. Patrick was born in Kilbreedy Minor, Mount Blakeney, Limerick, on land rented from the Blakeneys and worked by the Callaghans for 100+ years. The land was half was between Kilmallock, Limerick, and Charleville, Cork.

In 1844, when Patrick was only four, his father was evicted. A year of threats, arrests, and outright fighting occurred over the next year until the family was pushed out of their home. They lived for a short time on a neighbor’s property in a mud hut. Then the Blight struck.

In 1844, when Patrick was only four, his father was evicted. A year of threats, arrests, and outright fighting occurred over the next year until the family was pushed out of their home. They lived for a short time on a neighbor’s property in a mud hut. Then the Blight struck.

In the Autumn of 1845, a blight appeared unexpectedly among the potatoes. It was a black mold or fungus that caused much of the crop to rot in the fields, marking the beginning of the Great Famine (An Gorta Mor). The unique feature of the potato blight was the speed with which it spread. Eye witnesses said that a crop of potatoes in a field would be perfect in the morning time and by evening would be a rotting mass.

Four successive blighted harvests followed. Connacht and Munster were hit worst, where entire populations of towns had to abandon their homes and take to the road, searching for food. Bodies littered the countryside. Many died trying to eat weeds and any plants they could find, giving rise to a medical condition called “green mouth” from the stains. Many more died of typhus or dysentery. Between 1846 and 1849, over a million people died and another million immigrated, causing a population drop of almost 25 percent on the island. Mass graves appeared everywhere, and churches and towns could not properly update the death records. Five-year-old Patrick would have seen people dying all around him daily for years.

East Limerick, like East Galway and Roscommon, suffered slightly less than some other areas nearby because the land was more fertile and were planted with grains like wheat, barley, and oats, as well as potatoes. The famine was particularly bad in the west Cork area and in Kerry, but it was also bad in and around Charleville town. 72% of the people living in bothán near Charleville were wiped out by the famine. But not all people suffered during these years as some wealthy Irish Catholic middle-class farmers did very well buying land from tenants whose small holdings had been affected by the blight. With their potato crop failing, they had to sell their plot of land to buy food for their family and/or their passage out of the country. Mountblakeney was devastated. In 1841, there were 40 houses and 336 people living there. By 1851, only 55 people were left in 15 houses. By 1881, there were only 61 people in seven houses.

Four successive blighted harvests followed. Connacht and Munster were hit worst, where entire populations of towns had to abandon their homes and take to the road, searching for food. Bodies littered the countryside. Many died trying to eat weeds and any plants they could find, giving rise to a medical condition called “green mouth” from the stains. Many more died of typhus or dysentery. Between 1846 and 1849, over a million people died and another million immigrated, causing a population drop of almost 25 percent on the island. Mass graves appeared everywhere, and churches and towns could not properly update the death records. Five-year-old Patrick would have seen people dying all around him daily for years.

East Limerick, like East Galway and Roscommon, suffered slightly less than some other areas nearby because the land was more fertile and were planted with grains like wheat, barley, and oats, as well as potatoes. The famine was particularly bad in the west Cork area and in Kerry, but it was also bad in and around Charleville town. 72% of the people living in bothán near Charleville were wiped out by the famine. But not all people suffered during these years as some wealthy Irish Catholic middle-class farmers did very well buying land from tenants whose small holdings had been affected by the blight. With their potato crop failing, they had to sell their plot of land to buy food for their family and/or their passage out of the country. Mountblakeney was devastated. In 1841, there were 40 houses and 336 people living there. By 1851, only 55 people were left in 15 houses. By 1881, there were only 61 people in seven houses.

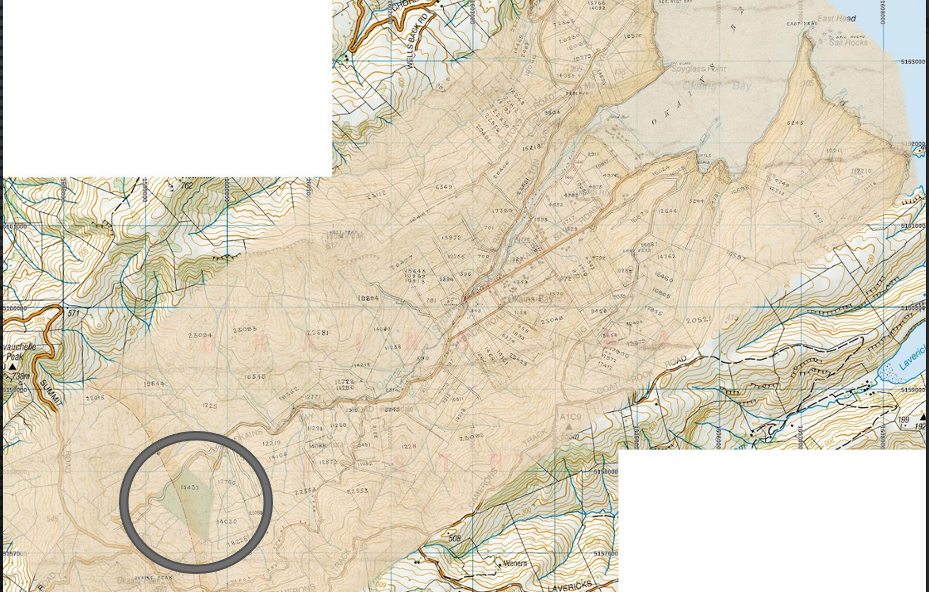

The family survived intact, but they had to move onto land rented by Patrick’s uncle John Carroll, near the holy well behind the old Effin Church yard. GoogleEarth shows the plot as the square surrounded by hedges in the top tight. The Holy Well is the circle on the top left. They eked out a living as best they could.

Patrick would have grown up with several Carroll cousins his own age. They all would have done work on the farms, but they would have also attended school in the Hedge Schools. That name would have been anachronistic by Patrick’s time and students would not have been taught hiding among the hedges. The more correct term would be “pay schools,” as the teachers would have been paid a nominal fee by the families. Classes would have been taught in a variety of locations—anywhere from a chapel or stone house to a mud hut, a cow barn, or in a cemetery. There were over 300 pay schools in Limerick by 1823. The curriculum would have included reading, writing, and arithmetic. Reading and writing would usually be in English, but sometimes in Irish, especially in West Limerick and Kerry. Latin and religion would be taught before mass on Sundays. County Kerry was well-known for its Latin school. Limerick was known for its math curriculum, where some of the teachers were also surveyors.

In 1854, Patrick’s oldest brother William went off to America to find work and to hopefully send money home. Three years later, Mary left for Australia. Around this time, Patrick’s mother died and his father decided it was time for the whole family to relocate.

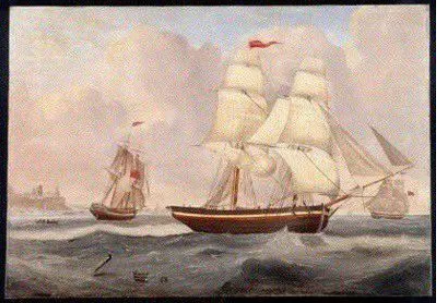

In July of 1858, a 17-year-old Patrick Callaghan boarded the Bee—a 1200-ton ship built in Boston in 1853—with his father and siblings, bound for Australia. They arrived in Adelaide, South Australia, on October 9, 1858, after a journey of 98 days during which six people died (five of them children under 1) and six more were born aboard the ship. Details of the voyage were posted in The South Australian Advertiser, Monday 11 October 1858:

The ship Bee, from Liverpool, arrived in our waters on Saturday, the 9th instant, having made her voyage in 98 days, although having very adverse winds to contend with throughout her progress. She reports leaving Liverpool on the 2nd July, and from her log we extract the following particulars of her voyage:

The Callaghan family on the passenger list included the father, John (42), along with his children William (20), Michael (19), Patrick (17), John (15), James (11), and Kate (7). Effin Parish records only exist for Kate and James and do not go back before 1843, though Michael’s baptism in Effin was confirmed by his marriage record. We do not have independent confirmation of the other brothers’ birthdates and places. On the passenger list published at http://www.theshipslist.com/ships/australia/bee1858.shtml, the family was designated with an N, meaning they were Nominee Emigrants.

Nominee Emigrants had their passage paid in exchange for staying in South Australia as laborers for at least two years. This was to keep the young men from running off to the gold fields in Victoria. Patrick apparently found work with a Mr. Thomas. After two years, though, he was off to Melbourne with his brothers Michael and James. Melbourne was not a success, and Patrick took another daring step, catching a ship headed for the gold fields in Otago, New Zealand. It is unknown when exactly he left for New Zealand. He would make a successful life in New Zealand and would return to Australia to visit family at least once (1882).

John Jr, Patrick, and James are also listed on the Incoming and outgoing Passenger Lists as having attended school aboard the Bee. It is noted that none of them had education in reading, writing, nor arithmetic at the start of the journey. After 57 days of schooling under Schoolmaster of the Ship John A. Boyd (himself listed as a General Emigrant), they had progressed through the 3rd book of reading instruction. John was noted as being “very perseverant,” James was “most attentive,” and Pat was “very attentive.” James, being younger, was still writing “large,” but his brothers had both progressed to “small” writing. They achieved different levels mathematically, but there is no legend explaining the designations of C.M, C.S., and C.A., respectively. William and Michael attended the Men’s school. They progressed from S.A. to S.D., indicating they came aboard with some education in the three R’s. Ellen and Kate did not attend the school.

Patrick would have grown up with several Carroll cousins his own age. They all would have done work on the farms, but they would have also attended school in the Hedge Schools. That name would have been anachronistic by Patrick’s time and students would not have been taught hiding among the hedges. The more correct term would be “pay schools,” as the teachers would have been paid a nominal fee by the families. Classes would have been taught in a variety of locations—anywhere from a chapel or stone house to a mud hut, a cow barn, or in a cemetery. There were over 300 pay schools in Limerick by 1823. The curriculum would have included reading, writing, and arithmetic. Reading and writing would usually be in English, but sometimes in Irish, especially in West Limerick and Kerry. Latin and religion would be taught before mass on Sundays. County Kerry was well-known for its Latin school. Limerick was known for its math curriculum, where some of the teachers were also surveyors.

In 1854, Patrick’s oldest brother William went off to America to find work and to hopefully send money home. Three years later, Mary left for Australia. Around this time, Patrick’s mother died and his father decided it was time for the whole family to relocate.

In July of 1858, a 17-year-old Patrick Callaghan boarded the Bee—a 1200-ton ship built in Boston in 1853—with his father and siblings, bound for Australia. They arrived in Adelaide, South Australia, on October 9, 1858, after a journey of 98 days during which six people died (five of them children under 1) and six more were born aboard the ship. Details of the voyage were posted in The South Australian Advertiser, Monday 11 October 1858:

The ship Bee, from Liverpool, arrived in our waters on Saturday, the 9th instant, having made her voyage in 98 days, although having very adverse winds to contend with throughout her progress. She reports leaving Liverpool on the 2nd July, and from her log we extract the following particulars of her voyage:

The Callaghan family on the passenger list included the father, John (42), along with his children William (20), Michael (19), Patrick (17), John (15), James (11), and Kate (7). Effin Parish records only exist for Kate and James and do not go back before 1843, though Michael’s baptism in Effin was confirmed by his marriage record. We do not have independent confirmation of the other brothers’ birthdates and places. On the passenger list published at http://www.theshipslist.com/ships/australia/bee1858.shtml, the family was designated with an N, meaning they were Nominee Emigrants.

Nominee Emigrants had their passage paid in exchange for staying in South Australia as laborers for at least two years. This was to keep the young men from running off to the gold fields in Victoria. Patrick apparently found work with a Mr. Thomas. After two years, though, he was off to Melbourne with his brothers Michael and James. Melbourne was not a success, and Patrick took another daring step, catching a ship headed for the gold fields in Otago, New Zealand. It is unknown when exactly he left for New Zealand. He would make a successful life in New Zealand and would return to Australia to visit family at least once (1882).

John Jr, Patrick, and James are also listed on the Incoming and outgoing Passenger Lists as having attended school aboard the Bee. It is noted that none of them had education in reading, writing, nor arithmetic at the start of the journey. After 57 days of schooling under Schoolmaster of the Ship John A. Boyd (himself listed as a General Emigrant), they had progressed through the 3rd book of reading instruction. John was noted as being “very perseverant,” James was “most attentive,” and Pat was “very attentive.” James, being younger, was still writing “large,” but his brothers had both progressed to “small” writing. They achieved different levels mathematically, but there is no legend explaining the designations of C.M, C.S., and C.A., respectively. William and Michael attended the Men’s school. They progressed from S.A. to S.D., indicating they came aboard with some education in the three R’s. Ellen and Kate did not attend the school.

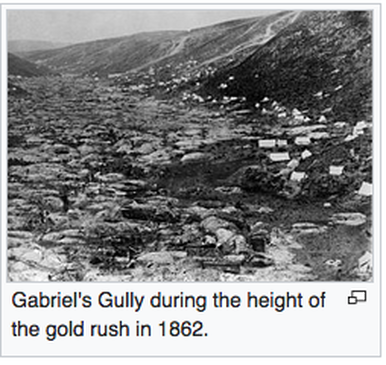

In June of 1861, Patrick would have heard about a new gold strike in Otago, on the South Island of New Zealand. Gabriel Read, an Australian prospector who had hunted gold in both California and Victoria, Australia, found gold in a creek bed at Gabriel's Gully, close to the banks of the Tuapeka River near Lawrence.

"At a place where a kind of road crossed on a shallow bar I shovelled away about two and a half feet of gravel, arrived at a beautiful soft slate and saw the gold shining like the stars in Orion on a dark frosty night".

The public heard about Read's find via a letter published in the Otago Witness, documenting a ten-day-long prospecting tour he had made. There was little reaction at first until John Hardy of the Otago Provincial Council stated that he and Read had prospected country "about 31 miles long by five broad, and in every hole they had sunk they had found the precious metal." By Christmas, 14,000 prospectors—mostly from the dwindling Australian goldfields—were on the Tuapeka and Waipori fields. The majority of them were laborers and tradesmen, in their late teens and twenties, and Patrick was among them.

The three Maori Islands that would late become New Zealand are generally thought to have been initially occupied between 900 and 1200 c.e. The first European visitor was Dutch explorer Abel Tasman who sighted land there on December 13, 1642, sailing the Heemskerck for the Dutch East India Company. He named what he thought was a peninsula Staaten Landt. The Dutch later renamed it New Zealand.

Europeans did not return until 1769 when Captain James Cook circumnavigated the three islands on the HMS Endeavour. Early European maps labelled the islands North (North Island), Middle (South Island), and South (Stewart’s Island). Settlement began to appear as early as 1835, at which time middle Island was referred to as New Munster and South Island was called New Leinster, after the southern provinces of Ireland. Since Stewart’s Island was so much smaller, the middle Island was officially renamed South Island in 1907 and South Island became Stewart’s Island. In response to a planned French settlement, representatives of the United Kingdom and Māori chiefs signed the Treaty of Waitangi on February 6, 1840, which (its English version) declared British sovereignty over the islands. In 1841, New Zealand became a colony within the British Empire.

We do not know exactly when nor on what ship Patrick traveled to New Zealand. There was a Patrick Callaghan who reached Christchurch on the William Miles (out of Bristol) on August 25, 1860, but further reseach showed he was five years older than our Patrick and had a wife and four-month-old-son who had probably been born abourd ship. So this Patrick was not ours.

According to his obituary (https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/CHP19070802.2.68):

About this time [late 1861], a Banks Peninsula settler named Tom Hughes, being anxious to secure hands to assist in opening up roads around Robinson’s Bay, built a schooner and sailed for Dundelin in the early part of 1862. There he secured about 42 men [including Patrick], and with them on board started back for Akaroa Harbour. On the way, the bargained for and secured a fisherman’s supply of barracoutata which they utilised. From the incident, the name “Barracouta Boys” was given to Tom Hughes’ shipment of men. Among the survivors of that historic shipload are Messrs Stewart, Sagar, Tizzard, Whitfield, Tom O’Connor, and J Duxborough (Duxbury).

One assumes that Patrick was one of the 42 men, but it is not confirmed. It seems that, from this schooner story, came a family memory that Patrick had been a ship’s captain. The book Tales from Banks Peninsula (Jabobson, 1893) has a slightly different story. Hughes’ schooner was the Barracouta, hence the name.

Patrick settled on the Banks Peninsula in 1865 and went to work building his fortune. According to Banks Peninsula, the Cradle of Canterbury (Ogilvie):

The 1870s saw another round of new arrivals. These included a number of Irish, the most intriguing of whom was probably Patrick Callaghan from County Cork. Callaghan, after adventures in South Australia and Otago plus some dairying at Long Lookout, shifted to Okains and married a daughter of Thomas Ware.

"At a place where a kind of road crossed on a shallow bar I shovelled away about two and a half feet of gravel, arrived at a beautiful soft slate and saw the gold shining like the stars in Orion on a dark frosty night".

The public heard about Read's find via a letter published in the Otago Witness, documenting a ten-day-long prospecting tour he had made. There was little reaction at first until John Hardy of the Otago Provincial Council stated that he and Read had prospected country "about 31 miles long by five broad, and in every hole they had sunk they had found the precious metal." By Christmas, 14,000 prospectors—mostly from the dwindling Australian goldfields—were on the Tuapeka and Waipori fields. The majority of them were laborers and tradesmen, in their late teens and twenties, and Patrick was among them.

The three Maori Islands that would late become New Zealand are generally thought to have been initially occupied between 900 and 1200 c.e. The first European visitor was Dutch explorer Abel Tasman who sighted land there on December 13, 1642, sailing the Heemskerck for the Dutch East India Company. He named what he thought was a peninsula Staaten Landt. The Dutch later renamed it New Zealand.

Europeans did not return until 1769 when Captain James Cook circumnavigated the three islands on the HMS Endeavour. Early European maps labelled the islands North (North Island), Middle (South Island), and South (Stewart’s Island). Settlement began to appear as early as 1835, at which time middle Island was referred to as New Munster and South Island was called New Leinster, after the southern provinces of Ireland. Since Stewart’s Island was so much smaller, the middle Island was officially renamed South Island in 1907 and South Island became Stewart’s Island. In response to a planned French settlement, representatives of the United Kingdom and Māori chiefs signed the Treaty of Waitangi on February 6, 1840, which (its English version) declared British sovereignty over the islands. In 1841, New Zealand became a colony within the British Empire.

We do not know exactly when nor on what ship Patrick traveled to New Zealand. There was a Patrick Callaghan who reached Christchurch on the William Miles (out of Bristol) on August 25, 1860, but further reseach showed he was five years older than our Patrick and had a wife and four-month-old-son who had probably been born abourd ship. So this Patrick was not ours.

According to his obituary (https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/CHP19070802.2.68):

About this time [late 1861], a Banks Peninsula settler named Tom Hughes, being anxious to secure hands to assist in opening up roads around Robinson’s Bay, built a schooner and sailed for Dundelin in the early part of 1862. There he secured about 42 men [including Patrick], and with them on board started back for Akaroa Harbour. On the way, the bargained for and secured a fisherman’s supply of barracoutata which they utilised. From the incident, the name “Barracouta Boys” was given to Tom Hughes’ shipment of men. Among the survivors of that historic shipload are Messrs Stewart, Sagar, Tizzard, Whitfield, Tom O’Connor, and J Duxborough (Duxbury).

One assumes that Patrick was one of the 42 men, but it is not confirmed. It seems that, from this schooner story, came a family memory that Patrick had been a ship’s captain. The book Tales from Banks Peninsula (Jabobson, 1893) has a slightly different story. Hughes’ schooner was the Barracouta, hence the name.

Patrick settled on the Banks Peninsula in 1865 and went to work building his fortune. According to Banks Peninsula, the Cradle of Canterbury (Ogilvie):

The 1870s saw another round of new arrivals. These included a number of Irish, the most intriguing of whom was probably Patrick Callaghan from County Cork. Callaghan, after adventures in South Australia and Otago plus some dairying at Long Lookout, shifted to Okains and married a daughter of Thomas Ware.

The property on Long Lookout point had been bought from a man named Waller in 1865. As Ogilvie says,

Waller caught gold fever and tramped over the Alps to Hokitika where he did well in the timber business before moving to the North Island. Patrick Callaghan, who bought Waller's property, ran15-20 cows and made cheese. He had previously worked in South Australia, been to the Otago diggings and worked on road gangs. His property was so dry that his cows had to be driven to Raupo Creek for water. After Arthur Waghorn bought out Callaghan, who went to farm at Okains Bay, the old houses built by Turner were pulled down.

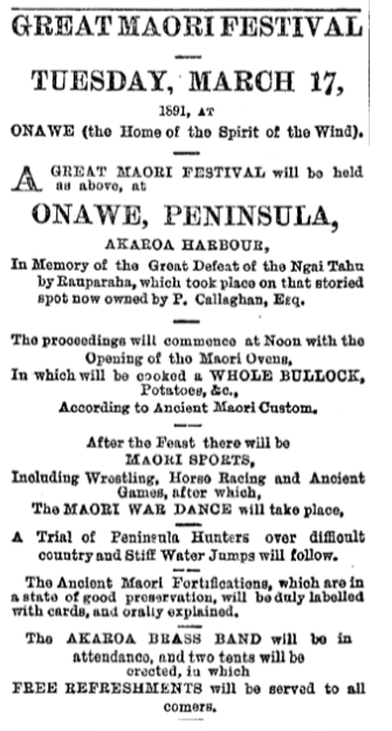

O’Kain’s Bay was named after an Irish naturalist O’Kain whose book a passing ship’s captain was reading. Okains Bay is known as Kawatea in Maori. It is important to the Ngai Tahu because a rangatira (chief) called Moki established his Pa or settlement here when Ngai Tahu migrated to Canterbury. Okains Bay has been recognized as the first landing place of Ngai Tahu on Banks Peninsula. Carbon dating of artifacts suggest that Maori were present in Okains bay in the 1300s.

[Note the spelling variations. Early New Zealand City Directories used O’Kain’s Bay, Several early maps and the Electoral Rolls sometimes used Okain’s Bay, By the late 19th Century, common used settled on Okains Bay.]

Waller caught gold fever and tramped over the Alps to Hokitika where he did well in the timber business before moving to the North Island. Patrick Callaghan, who bought Waller's property, ran15-20 cows and made cheese. He had previously worked in South Australia, been to the Otago diggings and worked on road gangs. His property was so dry that his cows had to be driven to Raupo Creek for water. After Arthur Waghorn bought out Callaghan, who went to farm at Okains Bay, the old houses built by Turner were pulled down.

O’Kain’s Bay was named after an Irish naturalist O’Kain whose book a passing ship’s captain was reading. Okains Bay is known as Kawatea in Maori. It is important to the Ngai Tahu because a rangatira (chief) called Moki established his Pa or settlement here when Ngai Tahu migrated to Canterbury. Okains Bay has been recognized as the first landing place of Ngai Tahu on Banks Peninsula. Carbon dating of artifacts suggest that Maori were present in Okains bay in the 1300s.

[Note the spelling variations. Early New Zealand City Directories used O’Kain’s Bay, Several early maps and the Electoral Rolls sometimes used Okain’s Bay, By the late 19th Century, common used settled on Okains Bay.]

According to Tales from Banks Peninsula,

The first people who really settled in Okain's were Messrs. Fleuty, Harley, Mason, and Webb. They were there before 1853. They bought up fifty acres among them. Mr. Thos. Ware, who soon afterwards arrived, bought one-fourth of it from them. He was the first to import sheep to the area. Messrs. Moore, Sefton, Gilbert, and others were also very early settlers in Okain's. They took up land on the same principle as Messrs. Webb, Mason, Fleuty, and Harley.

Mr. J. E. Thacker came to Okain's about thirty-eight years [1855] ago from Christchurch, and gradually bought up land, the six thousand acres purchased in all, now forming a magnificent estate. He erected a sawmill about fifteen or seventeen years ago, and soon cut all the suitable timber in the Bay. It was the largest sawmill ever at work on the Peninsula, and could cut 70,000 ft in a week, so that it did not take long to clear the land, a large number of hands being employed. The building in which the engine and machinery were once located is still in good preservation, and is now used as a wool-shed. The tramway to fetch down the logs to the mill went away to the top of the valley, and parts of it are still to be seen. The Alert, Jeanette, and Elizabeth were the vessels employed to carry the timber to Lyttelton, and they had all they could do to clear it away as it was cut.

As the bush was cut down fires became frequent, and a great deal of damage was done at times. The great fire which started in Pigeon Bay about five and twenty years ago, spread to Okain's. The fire lasted for a long time, and for weeks the sky was scarcely seen through the thick volumes of smoke. There have been several bush fires started in Okain's, but none as bad as this one. The summer had been a dry one, and the wind was favorable to its spreading. The whole Peninsula was ablaze, and after it had died out many wild pigs were found burnt to death. The native birds, besides, were never so plentiful afterwards as they were before the fire.

Patrick would have begun as a lumberjack and day laborer. As a later arrival and one of the few Irish Catholics in the area, Patrick was something of an outsider. Somewhere along the way, Patrick met Emma Ware.

Emma was born on August 2, 1846, in Chulmleigh, Devonshire, to Thomas Ware, a millwright, and Mary Ann Bond. Emma was baptized in the Anglican Church on August 23, 1846. She was the first of eight children. Her brother John Bond Ware was also born in Chumleigh, but the rest of her siblings were born in O’Kain’s Bay. In 1850, her father decided to move the family to the new colony in New Zealand.

In March of 1848, the Canterbury Association was formed in order to establish a Church of England settlement in New Zealand around a new city to be known as Christchurch. Between 1850 and 1853, some 28 ships would carry approximately 3500 settlers. The fifth ship to go was the Castle Eden, a barque, built in Sunderland, England in 1842, belonging to Port of London. The ships master was Capt. Timothy Thornhill and the Surgeon-Superintendent Dr Thomas Busick Haylock. The Ware family were among the 204 settlers.

There are several excellent websites about the ship and the journey. The most thorough is written by descendants of John and Ann Guilford can be found at https://winsomegriffin.com/Guilford/CanterburyEmigrants.html. A copy of Dr Haylock’s diary can be found at https://winsomegriffin.com/Guilford/Castle_Eden_SteerageDiary.html. To make a long story slightly shorter, passengers began boarding the Castle Eden at Woodlich Dock in London on September 25, 1850, and were tugged down river and headed for Plymouth the next day. She left Plymouth at 4 am on the 29th, but storms in the Channel forced her back to port. She finally got underway for real on October 18, four weeks after passengers initially came aboard.

Thigs did not get any easier. Some of the children came down with whooping cough, and a few adults developed typhoid fever. The food had been stored inaccessibly and was rotting in the hold. On top of that, the crew got into the rum and began ignoring orders. Dr Haylock made the call to put in at Cape Town where the entire crew arrested for mutiny. The ship was resupplied, and a new crew signed on. According to passenger diaries, the new crew was as bad or worse than the first. They finally reached Lyttleton Harbor on February 7, but a large number of the crew went on strike and would not man the boats to take passengers and their belongings ashore. The passengers were finally disembarked on February 14—149 days after first boarding the Castle Eden. In spite of all the troubles, there were only four deaths on the voyage while there were also two weddings and three births aboard.

As a fitting epitaph to Captain Thornhill’s leadership, according to https://www.peelingbackhistory.co.nz/castle-eden-the-6th-ship/

The Castle Eden last sailed in 1888 where she was wrecked on some rocks in the Red Sea. A following inquiry found the Captain at fault – in every way possible!!! The list was enormous!!!

The trip had started a month after Emma turned four. It would have been one of her earliest and strongest childhood memories.

The first people who really settled in Okain's were Messrs. Fleuty, Harley, Mason, and Webb. They were there before 1853. They bought up fifty acres among them. Mr. Thos. Ware, who soon afterwards arrived, bought one-fourth of it from them. He was the first to import sheep to the area. Messrs. Moore, Sefton, Gilbert, and others were also very early settlers in Okain's. They took up land on the same principle as Messrs. Webb, Mason, Fleuty, and Harley.

Mr. J. E. Thacker came to Okain's about thirty-eight years [1855] ago from Christchurch, and gradually bought up land, the six thousand acres purchased in all, now forming a magnificent estate. He erected a sawmill about fifteen or seventeen years ago, and soon cut all the suitable timber in the Bay. It was the largest sawmill ever at work on the Peninsula, and could cut 70,000 ft in a week, so that it did not take long to clear the land, a large number of hands being employed. The building in which the engine and machinery were once located is still in good preservation, and is now used as a wool-shed. The tramway to fetch down the logs to the mill went away to the top of the valley, and parts of it are still to be seen. The Alert, Jeanette, and Elizabeth were the vessels employed to carry the timber to Lyttelton, and they had all they could do to clear it away as it was cut.

As the bush was cut down fires became frequent, and a great deal of damage was done at times. The great fire which started in Pigeon Bay about five and twenty years ago, spread to Okain's. The fire lasted for a long time, and for weeks the sky was scarcely seen through the thick volumes of smoke. There have been several bush fires started in Okain's, but none as bad as this one. The summer had been a dry one, and the wind was favorable to its spreading. The whole Peninsula was ablaze, and after it had died out many wild pigs were found burnt to death. The native birds, besides, were never so plentiful afterwards as they were before the fire.

Patrick would have begun as a lumberjack and day laborer. As a later arrival and one of the few Irish Catholics in the area, Patrick was something of an outsider. Somewhere along the way, Patrick met Emma Ware.

Emma was born on August 2, 1846, in Chulmleigh, Devonshire, to Thomas Ware, a millwright, and Mary Ann Bond. Emma was baptized in the Anglican Church on August 23, 1846. She was the first of eight children. Her brother John Bond Ware was also born in Chumleigh, but the rest of her siblings were born in O’Kain’s Bay. In 1850, her father decided to move the family to the new colony in New Zealand.

In March of 1848, the Canterbury Association was formed in order to establish a Church of England settlement in New Zealand around a new city to be known as Christchurch. Between 1850 and 1853, some 28 ships would carry approximately 3500 settlers. The fifth ship to go was the Castle Eden, a barque, built in Sunderland, England in 1842, belonging to Port of London. The ships master was Capt. Timothy Thornhill and the Surgeon-Superintendent Dr Thomas Busick Haylock. The Ware family were among the 204 settlers.

There are several excellent websites about the ship and the journey. The most thorough is written by descendants of John and Ann Guilford can be found at https://winsomegriffin.com/Guilford/CanterburyEmigrants.html. A copy of Dr Haylock’s diary can be found at https://winsomegriffin.com/Guilford/Castle_Eden_SteerageDiary.html. To make a long story slightly shorter, passengers began boarding the Castle Eden at Woodlich Dock in London on September 25, 1850, and were tugged down river and headed for Plymouth the next day. She left Plymouth at 4 am on the 29th, but storms in the Channel forced her back to port. She finally got underway for real on October 18, four weeks after passengers initially came aboard.

Thigs did not get any easier. Some of the children came down with whooping cough, and a few adults developed typhoid fever. The food had been stored inaccessibly and was rotting in the hold. On top of that, the crew got into the rum and began ignoring orders. Dr Haylock made the call to put in at Cape Town where the entire crew arrested for mutiny. The ship was resupplied, and a new crew signed on. According to passenger diaries, the new crew was as bad or worse than the first. They finally reached Lyttleton Harbor on February 7, but a large number of the crew went on strike and would not man the boats to take passengers and their belongings ashore. The passengers were finally disembarked on February 14—149 days after first boarding the Castle Eden. In spite of all the troubles, there were only four deaths on the voyage while there were also two weddings and three births aboard.

As a fitting epitaph to Captain Thornhill’s leadership, according to https://www.peelingbackhistory.co.nz/castle-eden-the-6th-ship/

The Castle Eden last sailed in 1888 where she was wrecked on some rocks in the Red Sea. A following inquiry found the Captain at fault – in every way possible!!! The list was enormous!!!

The trip had started a month after Emma turned four. It would have been one of her earliest and strongest childhood memories.

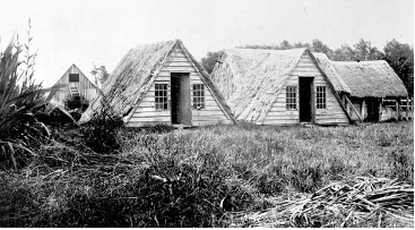

Unlike the Nominee Emigrants program that brought the Callaghans to South Australia, there was no obligation on the part of the Wares to stay in Christchurch. Thomas brought the family to Okains Bay, making them among the earliest pioneers to the area. There was no overland route. They would have had to wait in the immigration barracks until a whaling schooner could bring them around the headlands. The temporary barracks would have been comprised of V-huts. The buildings consisted of a thatched roof with door and windows at one end. They appear not to have had chimneys, suggesting cooking was done outside. These were built at Riccarton and photographed in 1864.

That 21-mile trip could take three days, if the weather were bad. Then they would walk, carrying any supplies and possessions, to where Tom had purchased a 20-acre household (as opposed to freehold) on part of Rural Section 359 in the valley where most of the settlers lived. If they were lucky, someone might give them a ride in an ox-cart, or as they were called in New Zealand, bullock-teams. The Ware family would become renowned for their bullock-teams well into the 20th Century.

Tom had to build their house, which was fine, him having been a millwright back home. His skills allowed him to serve as a blacksmith and wheelwright for the town. He started a small dairy with an earlier settler, John Thacker. It was only the second one in the valley. In the late 1850s, he built a saw mill with a pit saw. He later started a sheep ranch that, by 1887, had 700 sheep. (By comparison, Thacker had 7,000 sheep in 1887.) Thomas was been acknowledged as the first person to import sheep into the valley. [As an aside, what Americans call ranches, New Zealanders call farms--unless they are very large, and then they are called stations. In America, farms are primarily agricultural. If the primary purpose if livestock, we call it a ranch.]

During the 1850s, most of the development was centered on clearing the timber and scrub brush for farmland. The bay’s foreshore was then over 400 meters back from the present beach. Dense bush filled the whole valley and clothed the hills behind. According to an eyewitness account, “The sound of native birds during the dawn chorus was deafening.” The township of Okains Bay (there would not even be a general store or post office until 1883) grew slowly during Emma’s childhood. As Tom’s obituary said in 1891, he “had his hand in making the rough places smooth and transforming the wilderness into a flower garden.” That would be no easy feat. As Wendy Riley of the Okains Bay Museum said, “

Okains was rough in the early days of settlement, mostly occupied by farm hands and labourers. Lots of drinking! So, it was a bit like the wild west I think, and still has a reputation as being different (not in a good way) from the other bays on the Peninsula.

One can get a real sense of life at the time from an article titled A Bushman’s Life 130 Years Ago, written by Gordon Ogilvie and published in the Press in 1986. It can be found at https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/CHP19861231.2.84.1. Ogilvie had access to a 20-month diary written by a John Pope (or Cope) who was a pit sawyer for Tom Ware. According to Ogilvie,

Most settlers and bush workers lived off the land. A trading schooner called at the bay every month or two but the dwellers were always running short of basic items, such as flour and sugar. Pope used to help out the Ware larder by fishing and hunting. In the evenings, or on Sunday, which was a free day, he would go fishing for “eills” or herring in the river. He also learned to shoot “cawcaws” (kakas), the big bush parrots then numerous on the Peninsula and described them “as big as a fowl and beautiful eating.” Pope also bagged numbers of native pigeons and would walk down to the bar at the mouth of the river and stalk “red bills” which were usually too cunning for him. He was introduced by some sawyer friends to the savage excitement of pig hunting with dog and knife; and on another occasion tried to catch some “porposes” out in the bay. In December, 1857, Pope helped the Wares to build another wooden house, digging a saw pit beside the house site and felling three large trees nearby to provide the timber. His birthday on December 22 was celebrated with some help from his “master,” who supplied the “grog” for a party which lasted until daybreak.

The community was small—only 122 people lived there in 1858—but tightly knit. Being isolated as they were, they only had each other to rely upon. Ogilvie writes,

When misfortunes occurred the whole community closed ranks and rallied round the sufferers. If there was a funeral, such as for little Arthur Sefton, aged 3, whose clothes caught alight as he was warming himself in front of a fire, the entire settlement went to the funeral. Three months later Pope described the extensive search for a 4-year-old boy, (Joseph Fleurty, as records show), who went missing on the cliff track to Lavericks Bay and was never seen again.

Fire was a major danger in farming communities, especially in one that developed in bush country.

In October, 1858, a bush fire at Okains destroyed five whares (homes). In December, a fire which Thacker had lit for some purpose, destroyed a lot of sawn timber. Thacker would not pay any compensation to the owner so he was taken to court at Akaroa.

But there was celebration as well:

On March 15, 1858, “while am milking one of the cows I was shook and so whas all the bay tremendious.” This was Pope’s first earthquake. Two days later all was forgotten in the pandemonium of the bay’s St Patrick’s Day celebration. Thacker and Clifford were Irish, and Fleurty and Hurley probably so. Several of the bushmen certainly qualified. “Thear was great doings for so small a place thear whas a few kept it and they were continuly firing of guns and they had an iffige of some person and they burnt it in the evening.” (Cromwell? William of Orange? The Pope?) The festivities, singing and dancing, went on till morning.

That 21-mile trip could take three days, if the weather were bad. Then they would walk, carrying any supplies and possessions, to where Tom had purchased a 20-acre household (as opposed to freehold) on part of Rural Section 359 in the valley where most of the settlers lived. If they were lucky, someone might give them a ride in an ox-cart, or as they were called in New Zealand, bullock-teams. The Ware family would become renowned for their bullock-teams well into the 20th Century.

Tom had to build their house, which was fine, him having been a millwright back home. His skills allowed him to serve as a blacksmith and wheelwright for the town. He started a small dairy with an earlier settler, John Thacker. It was only the second one in the valley. In the late 1850s, he built a saw mill with a pit saw. He later started a sheep ranch that, by 1887, had 700 sheep. (By comparison, Thacker had 7,000 sheep in 1887.) Thomas was been acknowledged as the first person to import sheep into the valley. [As an aside, what Americans call ranches, New Zealanders call farms--unless they are very large, and then they are called stations. In America, farms are primarily agricultural. If the primary purpose if livestock, we call it a ranch.]

During the 1850s, most of the development was centered on clearing the timber and scrub brush for farmland. The bay’s foreshore was then over 400 meters back from the present beach. Dense bush filled the whole valley and clothed the hills behind. According to an eyewitness account, “The sound of native birds during the dawn chorus was deafening.” The township of Okains Bay (there would not even be a general store or post office until 1883) grew slowly during Emma’s childhood. As Tom’s obituary said in 1891, he “had his hand in making the rough places smooth and transforming the wilderness into a flower garden.” That would be no easy feat. As Wendy Riley of the Okains Bay Museum said, “

Okains was rough in the early days of settlement, mostly occupied by farm hands and labourers. Lots of drinking! So, it was a bit like the wild west I think, and still has a reputation as being different (not in a good way) from the other bays on the Peninsula.

One can get a real sense of life at the time from an article titled A Bushman’s Life 130 Years Ago, written by Gordon Ogilvie and published in the Press in 1986. It can be found at https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/CHP19861231.2.84.1. Ogilvie had access to a 20-month diary written by a John Pope (or Cope) who was a pit sawyer for Tom Ware. According to Ogilvie,

Most settlers and bush workers lived off the land. A trading schooner called at the bay every month or two but the dwellers were always running short of basic items, such as flour and sugar. Pope used to help out the Ware larder by fishing and hunting. In the evenings, or on Sunday, which was a free day, he would go fishing for “eills” or herring in the river. He also learned to shoot “cawcaws” (kakas), the big bush parrots then numerous on the Peninsula and described them “as big as a fowl and beautiful eating.” Pope also bagged numbers of native pigeons and would walk down to the bar at the mouth of the river and stalk “red bills” which were usually too cunning for him. He was introduced by some sawyer friends to the savage excitement of pig hunting with dog and knife; and on another occasion tried to catch some “porposes” out in the bay. In December, 1857, Pope helped the Wares to build another wooden house, digging a saw pit beside the house site and felling three large trees nearby to provide the timber. His birthday on December 22 was celebrated with some help from his “master,” who supplied the “grog” for a party which lasted until daybreak.

The community was small—only 122 people lived there in 1858—but tightly knit. Being isolated as they were, they only had each other to rely upon. Ogilvie writes,

When misfortunes occurred the whole community closed ranks and rallied round the sufferers. If there was a funeral, such as for little Arthur Sefton, aged 3, whose clothes caught alight as he was warming himself in front of a fire, the entire settlement went to the funeral. Three months later Pope described the extensive search for a 4-year-old boy, (Joseph Fleurty, as records show), who went missing on the cliff track to Lavericks Bay and was never seen again.

Fire was a major danger in farming communities, especially in one that developed in bush country.

In October, 1858, a bush fire at Okains destroyed five whares (homes). In December, a fire which Thacker had lit for some purpose, destroyed a lot of sawn timber. Thacker would not pay any compensation to the owner so he was taken to court at Akaroa.

But there was celebration as well:

On March 15, 1858, “while am milking one of the cows I was shook and so whas all the bay tremendious.” This was Pope’s first earthquake. Two days later all was forgotten in the pandemonium of the bay’s St Patrick’s Day celebration. Thacker and Clifford were Irish, and Fleurty and Hurley probably so. Several of the bushmen certainly qualified. “Thear was great doings for so small a place thear whas a few kept it and they were continuly firing of guns and they had an iffige of some person and they burnt it in the evening.” (Cromwell? William of Orange? The Pope?) The festivities, singing and dancing, went on till morning.

When he arrived at Okains Bay, two months after Pope’s diary ends, Torlesse was appalled by the disorderliness of the bay settlement. Most of the settlers and bush workers seemed to spend all their time getting drunk and thumping one another — or their wives.

Torlesse asked the Provincial Government to install a policeman. Nothing happened. Torlesse then proceeded to straighten out the community himself, largely by giving it other forms of relaxation apart from boozing and brawling. He began at Okains Bay, in 1860, the Peninsula’s first public library and organised concerts and sports days. However, all of this was too late for Pope whose diary mentions a number of all-night orgies, and records a variety of occasions when pairs of sawyers “fell out” or “had words.” John Thacker, though an enterprising colonist and a key figure in the development of Okains Bay, was often in the thick of legal squabbles relating to assault charges, biting dogs, stock trespass, non-payment, breach of contract, and so on. He employed many men and was regarded as a tough boss.

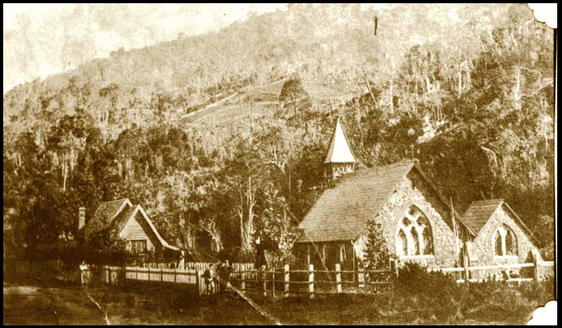

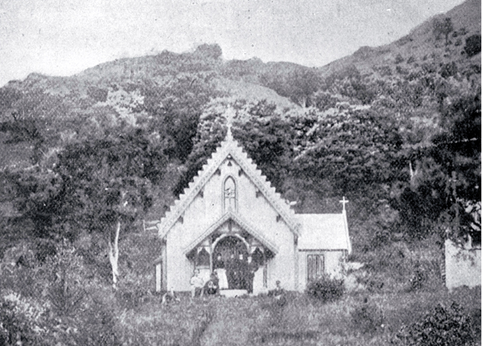

Torlesse quickly established a church school in a wooden building. A stone St John the Evangelist Church was finally erected in 1863. There is a story of some men crashing a church service and yelling obscenities before leaving!

This was the atmosphere in which Emma grew up. She probably attended the school, though her parents would have taught her basic reading, writing and arithmetic by then, and she would have availed herself of the books in the library. She seemed to like reading and was readingon the day she died. She would not have been expected to clear bush like her brother was (Pope talked about working and hunting alongside “Young Jackie”), but she would have had to help her mother with all the household chores and help raise her seven younger siblings. Cooking, cleaning, and laundry for a family of ten plus however may workers were employed (Pope was paid a pound a week plus board) would have been a herculean task.

Torlesse asked the Provincial Government to install a policeman. Nothing happened. Torlesse then proceeded to straighten out the community himself, largely by giving it other forms of relaxation apart from boozing and brawling. He began at Okains Bay, in 1860, the Peninsula’s first public library and organised concerts and sports days. However, all of this was too late for Pope whose diary mentions a number of all-night orgies, and records a variety of occasions when pairs of sawyers “fell out” or “had words.” John Thacker, though an enterprising colonist and a key figure in the development of Okains Bay, was often in the thick of legal squabbles relating to assault charges, biting dogs, stock trespass, non-payment, breach of contract, and so on. He employed many men and was regarded as a tough boss.

Torlesse quickly established a church school in a wooden building. A stone St John the Evangelist Church was finally erected in 1863. There is a story of some men crashing a church service and yelling obscenities before leaving!

This was the atmosphere in which Emma grew up. She probably attended the school, though her parents would have taught her basic reading, writing and arithmetic by then, and she would have availed herself of the books in the library. She seemed to like reading and was readingon the day she died. She would not have been expected to clear bush like her brother was (Pope talked about working and hunting alongside “Young Jackie”), but she would have had to help her mother with all the household chores and help raise her seven younger siblings. Cooking, cleaning, and laundry for a family of ten plus however may workers were employed (Pope was paid a pound a week plus board) would have been a herculean task.

It is unknown who or when Patrick and Emma first met, but it would have been difficult to avoid anyone for any length of time in such a small community. By early 1867, though, Emma was pregnant. Her parents would not have been happy, but, since they were pregnant with her when they got married, they could not be too sanctimonious about the situation. This was more complicated, though. Patrick must have insisted on getting married in the Catholic Church, and that would have required that Emma agree to a Catholic baptism and upbringing for her child. They decided to wait until after the birth to marry, possibly hoping things might take care of themselves. It would not have been a popular decision and must have been a very tense nine months. It is possible that, since the coach road from Akaroa to Christchurch would not be completed until 1872, that it made sense to wait until Spring to travel by sea and do both ceremonies at one time.

On October 12, 1867, their daughter Emily Agnes was born. Six weeks later on November 28, 1867, Patrick and Emma were wed at the Cathedral of the Blessed Sacrament in Christchurch. He was 27 years old, and she was 21. In the same ceremony, Emily was baptized into the Catholic faith. (The record lists her name as Amelia Agnes O’Callaghan.) The priest was Rev. Jean-Claude Chervier, and Emily’s sponsor was Thomas Connor.

Okain’s Bay continued to grow. By the end of the century, it had extensive farming, dairy, timber, and cocksfoot industries. Okains Bay School was built in 1872. In 1883, Okains Bay Store was erected, complete with post office. It is reputedly the oldest continuously run store in New Zealand. There was even a pub on the jetty about 1877, owned by John E Thacker, but it quickly burned down. The story is that the fire was set by the wives of his workers, as their husbands had to cash wage checks at the pub, where it was promptly spent on booze!

On October 12, 1867, their daughter Emily Agnes was born. Six weeks later on November 28, 1867, Patrick and Emma were wed at the Cathedral of the Blessed Sacrament in Christchurch. He was 27 years old, and she was 21. In the same ceremony, Emily was baptized into the Catholic faith. (The record lists her name as Amelia Agnes O’Callaghan.) The priest was Rev. Jean-Claude Chervier, and Emily’s sponsor was Thomas Connor.

Okain’s Bay continued to grow. By the end of the century, it had extensive farming, dairy, timber, and cocksfoot industries. Okains Bay School was built in 1872. In 1883, Okains Bay Store was erected, complete with post office. It is reputedly the oldest continuously run store in New Zealand. There was even a pub on the jetty about 1877, owned by John E Thacker, but it quickly burned down. The story is that the fire was set by the wives of his workers, as their husbands had to cash wage checks at the pub, where it was promptly spent on booze!

By 1874 (possibly as early as 1865), Patrick owned a freehold at Rural Section 15437 on O’Kains Bay, as shown on the Electoral Rolls. It was well up in the hills, not quite to the Summit Road that would run from Christchurch to Akaroa. When he sold it in 1889, it was described in the Akaroa Mail and Banks Peninsula Advertiser as “About 173 acres, situated on the Main Road, Okain's Bay; all in cocksfoot and sub-divided with six paddocks; fenced with posts, rails and wires, with barbed wire on top, together with seven-roomed house, dairy, shed, stock yards, good garden and orchard; well watered.” It is unclear whether this last meant the and was watered by a well or that there was plenty of water. By the way, cocksfoot (Dactylis glomerata) is a species of grass also known as orchard grass or cat grass (due to its popularity for use with domestic cats). It makes for good forage for cattle. As of 2023, the ranch is owned by Peter and Helen Heddell and is known as Glenrachney.

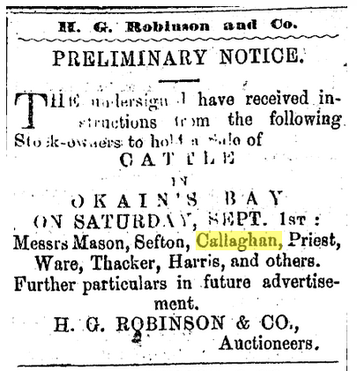

On this land, Patrick became a successful cattle rancher and horse breeder. He was often in the market papers for his sales. In 1879, he applied for a license to open a slaughter house on his property. He was well-thought-of enough that he was called as an expert witness in court cases regarding valuations of quality of livestock. He served on juries and was appointed foreman at least once. He also did not hesitate to go to court as the plaintiff when someone tried to pass a bad check or insult him.

In 1872, the road from Akaroa to Christchurch—and its connection to Okain’s Bay—was completed from a more-or-less bridle path to a full coach road. Patrick could drive cattle to market up Old O’Kain’s Bay Road to Summit Road and on to Akaroa. They likely made frequent trips to Akaroa and attended St. Patrick’s Church there. In 1885, he bought a 30-acre freehold in Akaroa, propably for cattle pens. In 1882 he bought a three-acre plot on Lavaud Road near the Church. It either had a house or he had one built there. It provided the family with a plaace to stay in Akaroa if they wanted to stay the night. Patrick later rented the house to the Sisters of Mercy to use as a convent until they could build their own.

On this land, Patrick became a successful cattle rancher and horse breeder. He was often in the market papers for his sales. In 1879, he applied for a license to open a slaughter house on his property. He was well-thought-of enough that he was called as an expert witness in court cases regarding valuations of quality of livestock. He served on juries and was appointed foreman at least once. He also did not hesitate to go to court as the plaintiff when someone tried to pass a bad check or insult him.

In 1872, the road from Akaroa to Christchurch—and its connection to Okain’s Bay—was completed from a more-or-less bridle path to a full coach road. Patrick could drive cattle to market up Old O’Kain’s Bay Road to Summit Road and on to Akaroa. They likely made frequent trips to Akaroa and attended St. Patrick’s Church there. In 1885, he bought a 30-acre freehold in Akaroa, propably for cattle pens. In 1882 he bought a three-acre plot on Lavaud Road near the Church. It either had a house or he had one built there. It provided the family with a plaace to stay in Akaroa if they wanted to stay the night. Patrick later rented the house to the Sisters of Mercy to use as a convent until they could build their own.

In 1878, Patrick did what his brothers William and Michael did and got involved in local politics by joining to Okains Bay Road Board. But Patrick’s experience was rockier than those of his brothers. He won the election handily, but when he showed up for the first meeting, it was claimed that the election was illegal, and he was not allowed to sit. A petition went to the Resident Magistrate (RM) to have his election overturned. For good or ill, Patrick decided to take it to the court of public opinion and sent a letter to the editor of the Akaroa Mail and Banks Peninsula Advertiser:

To the Editor of the Akaroa Mail.

Sir, —Having been elected to serve as a member of the Okain's Bay Road Board on the 23rd of March last by a majority of 16 votes, in opposition to the Government candidate, Mr T. Oldridge, who is-son-in-law to the present clerk, I considered that I had achieved a more than ordinary victory, and was consequently jubilant thereat, seeing that a species of trick or, may be, tricks, for anything I know to the contrary, had been tried on to prevent my return. For when Mr. Gilbert, an elector who is rather deaf, presented himself, it was agreed upon between my scrutineer and the returning officer that, they should ask him for whom he intended to vote; upon which he replied—'- for Callaghan." whereupon the returning officer, Mr David Wright, took a voting paper, and, proceeding to the other end of the room, operated on the paper, and was in the act of dropping the same into the ballot-box when my scrutineer, Mr M. Connor interposed—determined to see that no" mistake should defeat my return—when, Io and behold, my name had been scratched out. David was holding up the paper when stopped by Connor, and asserted that it was all right; but Mick was not to be bluffed in this manner, and the paper proved to be all wrong. It was subsequently torn up, and another put in in its place with the proper name scratched out. This was, at all events, move No. 1. On presenting myself at the Road Board office on Saturday last, I was informed by the Chairman, Mr J. B. Barker, that I should not be allowed to sit, as my election was informal. Thus, he was at once acting the double part of accuser and judge with a vengeance. Is it not customary and lawful in such cases to wait and know the decision of the Resident Magistrate? I had not the slightest wish or desire to take part in the proceedings of the Board if unlawfully elected, yet it does seem to me that a very great deal of trouble is being taken to prevent an outsider like myself disturbing the harmony of such a beautiful family union as this Okain's Bay Road Board seems to be.

Yours, PATRICK CALLAGHAN. Okain's Bay, April 2.

The Board Clerk, Mr. David Wright, objected and responded by saying of Patrick’s letter, “I say, is not true, but the contrary, and is got up in that compound of Jesuitry and blarney in which many of the “Exiles of Erin” are apt to indulge.” Patrick replied:

Sir,—At the present, when the case of my election as a member of the Okain's Bay Road Board is to some extent sub judice, I do not wish to go into a newspaper correspondence, but I cannot but remark that your correspondent, D. Wright, in your issue of the 12th inst, quite overlooks the charge made by me, viz., that the Returning-officer did, in contravention of clause 32 of the Regulation of Local Elections Act, 1875, draw through the name of a voter who intended to vote for myself. The great difficulty I had with the Returning-officer in obtaining the necessary nomination forms is a matter of notoriety to many of my neighbours, and must be the result of more than the usual care taken by these officers in seeing that the law is complied with. As to the objection being taken by one of my supporters, I have no remarks, only that I wish to take my seat legally, and to see that the business of the Board is carried on, if not legally, at least honestly. Yours, &c, PATRICK CALLAGHAN.

On April 16, the case finally went to court:

The petition heard in the Resident Magistrate's Court on Tuesday last, against the election of Mr P. Callaghan to a seat on the Okain's Road Board, on the ground of want of proper qualification on the part of one of that gentleman's constituents, is the first case under the " Local Elections Act" that has been tried in this district, and, if its hearing has not served the purpose of proving to the public the efficacy of the Act in question, it has, at any rate added the notoriety, in a degree by no means to be envied, of the Okain's Road Board. The facts of this remarkable case are, briefly, as follows : —Mr P. Callaghan is returned as a member of the Okain's Road Board by a large majority. At the first meeting of the Board after the election, the Chairman learns from another member that one of the persons signing Mr Callaghan's nomination paper was not legally qualified to vote. The matter is accordingly discussed by the Board, the result being that Mr Callaghan, on his arrival, is told by the Chairman that he cannot take his seat as a member of the Board, as his election is illegal, and the case must be tried. All this seems on the face of it to be nothing more than is correct ; but the reverse side of the picture shows either an amount of gross ignorance on the part of the Board, or characterises the whole proceeding as a flagrant case of sophistry and chicanery, urged on, it would seem, by personal animus or party spite, for incredible as it appears, even while refusing to allow Mr P. Callaghan to take his seat on the Board, the Chairman, Mr J. B. Barker, as well as the Clerk to the Board, Mr D. Wright, were aware that the person whose qualification to vote they disputed was actually at the time on the Electoral Roll, and had paid all rates. That a Chairman of a Road Board should be ignorant that this was in itself sufficient qualification seems so improbable that we can only put the other construction on the action of the petitioners, and stigmatise it as a disgraceful attempt to oust a member from his justly won position on the Board to gratify personal motives. The evidence of Mr Oldridge, another of the petitioners, speaks for itself. He says : —" I was told that Mr Callaghan was illegally elected. I have no personal feeling in the matter at all. I signed because I was asked to, but know nothing about the matter." This shows very conclusively that Mr Oldridge was, as the Resident Magistrate aptly remarked, merely a catspaw, but at the same time it does not reflect much credit on that gentleman's astuteness in allowing himself to be made so ready a tool of by Messrs Barker and Co. The care with which the rates were collected from Mr Fluerty, the gentleman whose signature to the nomination paper was objected to, stands out in bold relief against the carefulness with which the Board, that is the Clerk, for these two are synonymous; we understand, who received those rates, denied his qualification to vote, an instance of memory, combined with forgetfulness" that is positively startling, but not without parallel. The whole matter, though trivial, may be productive of some good in exposing certain phases of character comprised in the human machinery, working the Okain's Road Board, and should open not a little the eyes of the ratepayers in that district to whose lot at some time or other it may chance to fall, in the face of the powers that be to contest an election for a seat on the Board. Some such rule as obtains in other countries with regard to petitions against elected candidates, viz., that the objector shall at the time of laying the objection deposit a sum of money, which sum in case of the election being sustained is forfeited, might with advantage be brought into force in this colony also, and serve as a wholesome check to such paltry and disgraceful attempts as the above. It would be hard indeed to find a more convincing argument for the necessity of some such protection to candidates from similar disagreeable, and apparently malicious, persecution and annoyance.

So Jesuitry and blarney triumphed over sophistry and chicanery.

As an afterward, these was another letter to the editor, purportedly from an old schoolmate of Patrick’s named Tim Flaherty. He objects to Patrick talking “Frinch,” in relation to him using the Latin term sub judice. There are so many misspellings and malapropisms that one has to assume it is an anti-Irish satire written by someone in Wright’s camp. One can almost hear the sotto voce “uppity Papist!”

To the Editor of the Akaroa Mail.

Sir, —Having been elected to serve as a member of the Okain's Bay Road Board on the 23rd of March last by a majority of 16 votes, in opposition to the Government candidate, Mr T. Oldridge, who is-son-in-law to the present clerk, I considered that I had achieved a more than ordinary victory, and was consequently jubilant thereat, seeing that a species of trick or, may be, tricks, for anything I know to the contrary, had been tried on to prevent my return. For when Mr. Gilbert, an elector who is rather deaf, presented himself, it was agreed upon between my scrutineer and the returning officer that, they should ask him for whom he intended to vote; upon which he replied—'- for Callaghan." whereupon the returning officer, Mr David Wright, took a voting paper, and, proceeding to the other end of the room, operated on the paper, and was in the act of dropping the same into the ballot-box when my scrutineer, Mr M. Connor interposed—determined to see that no" mistake should defeat my return—when, Io and behold, my name had been scratched out. David was holding up the paper when stopped by Connor, and asserted that it was all right; but Mick was not to be bluffed in this manner, and the paper proved to be all wrong. It was subsequently torn up, and another put in in its place with the proper name scratched out. This was, at all events, move No. 1. On presenting myself at the Road Board office on Saturday last, I was informed by the Chairman, Mr J. B. Barker, that I should not be allowed to sit, as my election was informal. Thus, he was at once acting the double part of accuser and judge with a vengeance. Is it not customary and lawful in such cases to wait and know the decision of the Resident Magistrate? I had not the slightest wish or desire to take part in the proceedings of the Board if unlawfully elected, yet it does seem to me that a very great deal of trouble is being taken to prevent an outsider like myself disturbing the harmony of such a beautiful family union as this Okain's Bay Road Board seems to be.

Yours, PATRICK CALLAGHAN. Okain's Bay, April 2.

The Board Clerk, Mr. David Wright, objected and responded by saying of Patrick’s letter, “I say, is not true, but the contrary, and is got up in that compound of Jesuitry and blarney in which many of the “Exiles of Erin” are apt to indulge.” Patrick replied:

Sir,—At the present, when the case of my election as a member of the Okain's Bay Road Board is to some extent sub judice, I do not wish to go into a newspaper correspondence, but I cannot but remark that your correspondent, D. Wright, in your issue of the 12th inst, quite overlooks the charge made by me, viz., that the Returning-officer did, in contravention of clause 32 of the Regulation of Local Elections Act, 1875, draw through the name of a voter who intended to vote for myself. The great difficulty I had with the Returning-officer in obtaining the necessary nomination forms is a matter of notoriety to many of my neighbours, and must be the result of more than the usual care taken by these officers in seeing that the law is complied with. As to the objection being taken by one of my supporters, I have no remarks, only that I wish to take my seat legally, and to see that the business of the Board is carried on, if not legally, at least honestly. Yours, &c, PATRICK CALLAGHAN.

On April 16, the case finally went to court:

The petition heard in the Resident Magistrate's Court on Tuesday last, against the election of Mr P. Callaghan to a seat on the Okain's Road Board, on the ground of want of proper qualification on the part of one of that gentleman's constituents, is the first case under the " Local Elections Act" that has been tried in this district, and, if its hearing has not served the purpose of proving to the public the efficacy of the Act in question, it has, at any rate added the notoriety, in a degree by no means to be envied, of the Okain's Road Board. The facts of this remarkable case are, briefly, as follows : —Mr P. Callaghan is returned as a member of the Okain's Road Board by a large majority. At the first meeting of the Board after the election, the Chairman learns from another member that one of the persons signing Mr Callaghan's nomination paper was not legally qualified to vote. The matter is accordingly discussed by the Board, the result being that Mr Callaghan, on his arrival, is told by the Chairman that he cannot take his seat as a member of the Board, as his election is illegal, and the case must be tried. All this seems on the face of it to be nothing more than is correct ; but the reverse side of the picture shows either an amount of gross ignorance on the part of the Board, or characterises the whole proceeding as a flagrant case of sophistry and chicanery, urged on, it would seem, by personal animus or party spite, for incredible as it appears, even while refusing to allow Mr P. Callaghan to take his seat on the Board, the Chairman, Mr J. B. Barker, as well as the Clerk to the Board, Mr D. Wright, were aware that the person whose qualification to vote they disputed was actually at the time on the Electoral Roll, and had paid all rates. That a Chairman of a Road Board should be ignorant that this was in itself sufficient qualification seems so improbable that we can only put the other construction on the action of the petitioners, and stigmatise it as a disgraceful attempt to oust a member from his justly won position on the Board to gratify personal motives. The evidence of Mr Oldridge, another of the petitioners, speaks for itself. He says : —" I was told that Mr Callaghan was illegally elected. I have no personal feeling in the matter at all. I signed because I was asked to, but know nothing about the matter." This shows very conclusively that Mr Oldridge was, as the Resident Magistrate aptly remarked, merely a catspaw, but at the same time it does not reflect much credit on that gentleman's astuteness in allowing himself to be made so ready a tool of by Messrs Barker and Co. The care with which the rates were collected from Mr Fluerty, the gentleman whose signature to the nomination paper was objected to, stands out in bold relief against the carefulness with which the Board, that is the Clerk, for these two are synonymous; we understand, who received those rates, denied his qualification to vote, an instance of memory, combined with forgetfulness" that is positively startling, but not without parallel. The whole matter, though trivial, may be productive of some good in exposing certain phases of character comprised in the human machinery, working the Okain's Road Board, and should open not a little the eyes of the ratepayers in that district to whose lot at some time or other it may chance to fall, in the face of the powers that be to contest an election for a seat on the Board. Some such rule as obtains in other countries with regard to petitions against elected candidates, viz., that the objector shall at the time of laying the objection deposit a sum of money, which sum in case of the election being sustained is forfeited, might with advantage be brought into force in this colony also, and serve as a wholesome check to such paltry and disgraceful attempts as the above. It would be hard indeed to find a more convincing argument for the necessity of some such protection to candidates from similar disagreeable, and apparently malicious, persecution and annoyance.

So Jesuitry and blarney triumphed over sophistry and chicanery.

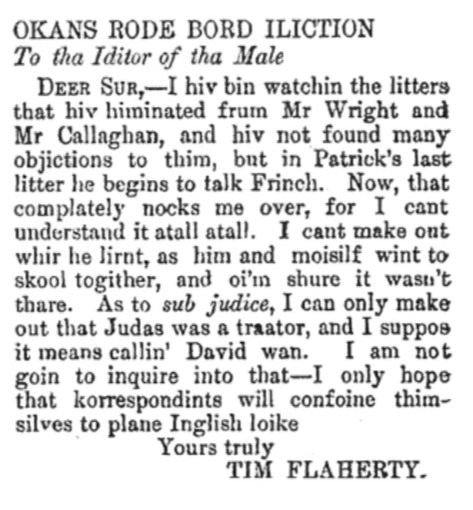

As an afterward, these was another letter to the editor, purportedly from an old schoolmate of Patrick’s named Tim Flaherty. He objects to Patrick talking “Frinch,” in relation to him using the Latin term sub judice. There are so many misspellings and malapropisms that one has to assume it is an anti-Irish satire written by someone in Wright’s camp. One can almost hear the sotto voce “uppity Papist!”

Another part of the story played out in court at the same time. Another member of the Board family was Patrick’s neighbor John E Thacker, a sheep rancher whose son William was a member of the Road Board. A public road known as Old Okains Bay Road led through Thacker’s land up to the Summit Road. Patrick and his neighbors often used the road to drive cattle to market. Thacker claimed the road was not public and put up a gate, which Patrick tore down. This went to court as well and Patrick won out. But the problem festered. Four years later, Thacker tried to take advantage of Patrick being in Australia and asked the Road Board to declare the road on his land closed. Patrick had rotated off the Board by then. His old Barracouta Boy compatriot John Duxbury delivered Patrick’s petition with 70 signatures to stop it. Patrick won again.

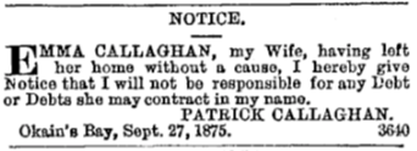

At the end of 1878, Patrick and John Thacker were in court before the resident magistrate. Patrick sued John for assault (John countersued for assault) and Patrick sued MRS. Thacker for threatening language. The assault charges were thrown out as each seems to had struck the other. The threatening language charge was dismissed after Mrs Thacker testified that she advised Patrick to “go home and look after his wife.” The Court’s response was “Neither Bench nor counsel could quite see how this excellent advice could be said to be contrary to the statute in such case made and provided as in the information it was alleged to be.” Given the events of three years earlier (Emma had run away for a short time), Patrick probably took this as a low blow.

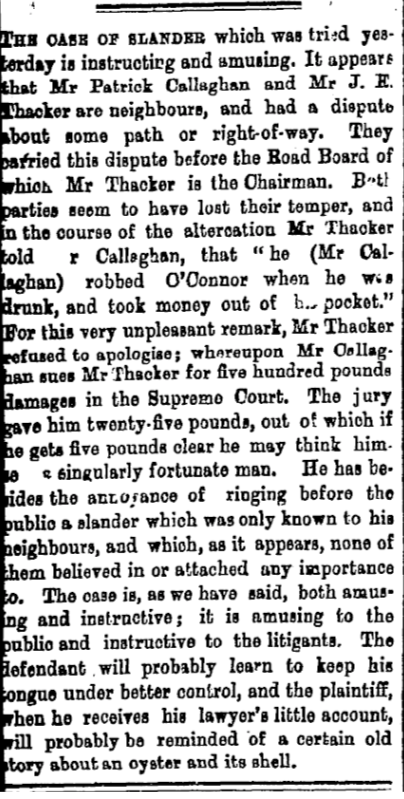

In 1883, Thacker again brought the road closure to the Road Board Office again. This time Patrick and Thacker got into a heated argument that ended in a £500 slander charge by Patrick against Thacker which went to court on April 17, 1883:

Patrick Callaghan, the plaintiff: I am a cattle-dealer. I have resided at Okain's Bay 18 years. Mr Thacker is a sheep farmer, and has from 3000 to 4000 acres. In August last, he was Chairman of the Road Beard. On August 28, I went to the Road Board Office in consequence of a notice re the opening of some road. A dispute arose between me and defendant about a road that he said went through my land. I have about 190 acres. There were present Messrs Ware, James, John Batter, a member of the Board, and Mr Charles Moore, Clerk to the Board. There was also Mr William Thacker, defendant's son, a member of the Board. We talked about some obstructions to a road, and then about a road going through my land. I told him there was no such thing as a road through my land. He called me a liar, and said there was. I thanked him, and still persisted that there was no road. He said he would bet me either £5 or £10, I don't know exactly which, that there was. I said I would take up the bet. He asked the Clerk for a blank cheque. The Clerk had not one, so I gave him one, and took out of my pocket some money, I don't know how much, and put it on the table. He declined to take up the bet. He said he did not carry money about with him like that. I wanted him to put the money into the bands of Mr Barker, a member of the Board. He said I might do the same with him as I did with O'Connor. He said I robbed him, and took the money out of his pocket when he was drunk. This is the book he referred to (producing a pocket-book). I told him he had gone too far with me this time, and I turned to the witnesses, and called them one after the other to witness what Mr Thacker had said, as I intended making him prove it. Some 13 years previously there was a difference between O'Connor and me about a partnership business. It was after our partnership was dissolved. I told defendant the circumstances of the case. O'Connor had taken this pocket-book, containing some £130, out of the bedroom where I was sleeping. He acknowledged that he had taken it, and claimed to be entitled to a portion of it. I did not take anything out of O'Connor's pocket. Defendant advised me to take proceedings in the Akaroa R.M. Court.

Cross-examined: I don't feel any animosity towards defendant. I have always spoken to him when I met him except yesterday. There has been a squabble between us, as to the road through my section, but there has been no other squabble between us. It first arose on August 26. Before then we were on good terms, and since. On the boat yesterday, he was on one part of it and I on another. Mr Thacker was in the chair at the Road Board. He stood up, but no one else acted as Chairman. We argued the thing before the members. The argument may have lasted half an hour to an hour or a little more. There was one thing I forgot. Mr W. Thacker told me if I had not come to the Board, there would not have been the squabble. Defendant first offered to bet. The bet was to be determined by some surveyor. I did not intend to leave it to the Board, for defendant was all the Board on that occasion. (Laughter). I have known all the members of the Board for about 18 years. It is a small place, and we are pretty well known to one another. The words I complain of were uttered just after I had taken out the blank cheque. I did not jump about the room, or clap my hands. I don't remember saying, "Now I have got you at last, I will have you for defamation." I was more excited than I am now. I gave him to understand that I would pull him for defamation, or make him prove what he had said. I repeated the words afterwards to several of my neighbours. About fourteen years ago I took defendant's advice as to laying an information against O'Connor.

Re-examined: Defendant never made any attempt to apologise. I called upon him by my solicitor to apologise in the Akaroa Mail.