Michael Millerick and Marry Taaffe

Husband: Michael Millerick

Birth: 10 May 1836, Balynona North, Co Cork, Ireland

Father: John Millerick Mother: Mary Connell

Death: 4 Jan 1892, San Francisco, CA

Wife: Mary Taaffe

Birth: 1841, Shanballysallagh, Co Clare, Ireland

Father: George Taaffe, Jr Mother: Mary Murphy

Death: 31 Dec 1891, San Francisco, CA

Marriage: 11 May 1868, St. Vincent’s Church, Petaluma, CA

Children: John Millerick (1869-1951)

George Millerick (1870-1951)

Mary (Mame) Millerick (1871-1948)

Ellen Millerick (1873-1908)

Hannah (Annie) Millerick (1874-1969)

Phillip Millerick (1875-1918)

Katherine (Kate) Millerick (1880-1916)

Thomas Millerick (1881-1946)

Margaret Theresa Millerick (1883-1919)

William Steven Millerick (1887-1965)

Birth: 10 May 1836, Balynona North, Co Cork, Ireland

Father: John Millerick Mother: Mary Connell

Death: 4 Jan 1892, San Francisco, CA

Wife: Mary Taaffe

Birth: 1841, Shanballysallagh, Co Clare, Ireland

Father: George Taaffe, Jr Mother: Mary Murphy

Death: 31 Dec 1891, San Francisco, CA

Marriage: 11 May 1868, St. Vincent’s Church, Petaluma, CA

Children: John Millerick (1869-1951)

George Millerick (1870-1951)

Mary (Mame) Millerick (1871-1948)

Ellen Millerick (1873-1908)

Hannah (Annie) Millerick (1874-1969)

Phillip Millerick (1875-1918)

Katherine (Kate) Millerick (1880-1916)

Thomas Millerick (1881-1946)

Margaret Theresa Millerick (1883-1919)

William Steven Millerick (1887-1965)

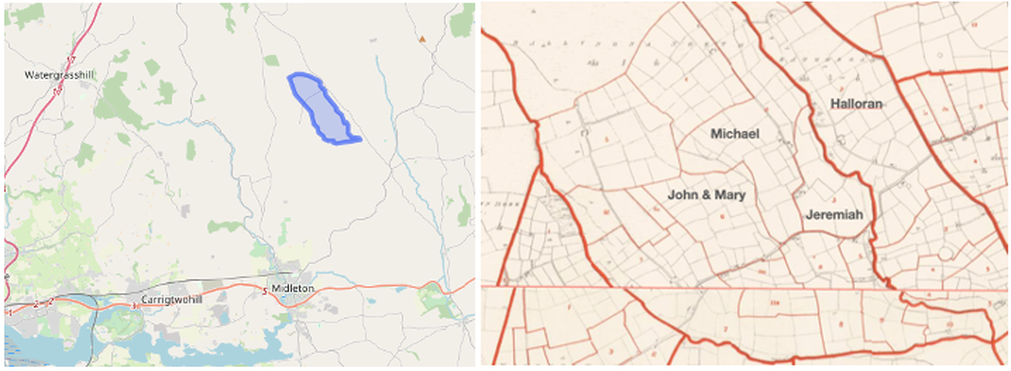

Michael Millerick was born on May 10, 1836, in Ballynona North, to John Millerick and Mary Connell. He seems to have been the oldest of seven—or possibly ten—children. We say “seems” because the baptismal records indicate so, but Michael’s daughter Annie Fredericks said there were three other brothers—John, William, and Patrick—of which no baptismal or travel record have been found. John and Mary were married in 1832 in Rathcormac, Cork, Ireland. Given that all their documented children were born about two years apart, it is odd that they did not have a child for the first four years of their marriage. It would not have been surprising for the first son to be named after the father or paternal grandfather, so a John or William might have preceded Michael.

Michael’s grandfather and uncles were likely involved in the Tithe War. The Tithe War (Irish: Cogadh na nDeachúna) was a reaction to the enforcement of tithes on the Roman Catholic majority for the upkeep of the Church of Ireland. Tithes were payable in cash or kind and payment was compulsory, irrespective of an individual's religious adherence. It was much less a war than a series of incidents of nonviolent civil disobedience with the occasional violent episode. One such incident occurred near Rathcormac on December 18, 1834.

Since 1830, Catholic tenant farmers across much of Ireland had been withholding the tithes they were obliged to pay to the vicar of the local Church of Ireland parish. Archdeacon William Ryder was the rector of the parish of Gortroe (Gurtroe), and also a resident magistrate. His tithes fell due on November 1, 1834, a distraining party set out led by Archdeacon Ryder and Captain Richard Boyle Bagley, RM, and William Cooke Collis, a Justice of the Peace. The party was met at Bartlemy, a crossroads hamlet, by a military escort of approximately 100 men. The escort comprised 12 mounted troops of the 4th Royal Irish Dragoon Guards under Major Waller, two companies of the 29th (Worcestershire) Regiment of Foot under Lieutenant Tait, and “a very small part” of the Irish Constabulary under Captain Pepper. A crowd of approximately 250 locals began pelting the party with stones before retreating to the plot of Widow Ryan where a barricade had been built. Ryan owed 40 shillings in arrears and the party advanced to collect either the money or produce of equal value. The Riot Act was read and the soldiers advanced but were beaten back by “spades, sticks, and stones” and sustained injuries for 45 minutes. Waller ordered them to open fire. Nine were killed at the scene and 45 injured, with at least 3 dying later from their wounds. None of the distraining party or escort were killed, though many were injured by rocks, cudgels and pikes. The crowd dispersed, and Ryan paid her tithe.

The conflict had the support of the Roman Catholic clergy, and a letter written by the Bishop of Kildare became the rallying cry:

There are many noble traits in the Irish character, mixed with failings which have always raised obstacles to their own well-being; but an innate love of justice, and an indomitable hatred of oppression, is like a gem upon the front of our nation which no darkness can obscure. To this fine quality I trace their hatred of tithes; may it be as lasting as their love of justice!

Things seem to have been more quiet in Ballynona North, Dungourney, where Michael was growing up. According to Lewis’ A Topological Map of Ireland (1837),

DUNGOURNEY, a parish, partly in the barony of Imokilly, but chiefly in that of Barrymore, county of Cork, and province of Munster, 4½ miles (N.) from Castlemartyr, on the road from Cork to Youghal; containing 2640 inhabitants. This parish comprises 8991 statute acres, of which 5925 are applotted under the tithe act, and valued at £4529 per annum; about 70 acres are woodland, nearly one-fourth of the land is waste, and the remainder is arable and pasture. The soil is generally good, but the system of agriculture is in an unimproved state; there are some quarries of common red stone, which is worked for various purposes, and there is a moderate supply of turf for fuel. The Dungourney river rises in the neighbouring hills of Clonmult, and flows through a deep glen in the parish, assuming near the church a very romantic appearance, and towards the southern boundary adding much beauty to the highly cultivated and richly wooded demesne of Brookdale, the seat of A. Ormsby, Esq. The other seats are Ballynona, that of R. Wigmore, Esq.; Ballynona Cottage, of H, Wigmore, Esq.; and Young Grove, of C.

The current Ballynona House was built around 1900 and serves as a Bed & Breakfast. A number of Millerick descendants have stayed there.

Michael’s grandfather and uncles were likely involved in the Tithe War. The Tithe War (Irish: Cogadh na nDeachúna) was a reaction to the enforcement of tithes on the Roman Catholic majority for the upkeep of the Church of Ireland. Tithes were payable in cash or kind and payment was compulsory, irrespective of an individual's religious adherence. It was much less a war than a series of incidents of nonviolent civil disobedience with the occasional violent episode. One such incident occurred near Rathcormac on December 18, 1834.

Since 1830, Catholic tenant farmers across much of Ireland had been withholding the tithes they were obliged to pay to the vicar of the local Church of Ireland parish. Archdeacon William Ryder was the rector of the parish of Gortroe (Gurtroe), and also a resident magistrate. His tithes fell due on November 1, 1834, a distraining party set out led by Archdeacon Ryder and Captain Richard Boyle Bagley, RM, and William Cooke Collis, a Justice of the Peace. The party was met at Bartlemy, a crossroads hamlet, by a military escort of approximately 100 men. The escort comprised 12 mounted troops of the 4th Royal Irish Dragoon Guards under Major Waller, two companies of the 29th (Worcestershire) Regiment of Foot under Lieutenant Tait, and “a very small part” of the Irish Constabulary under Captain Pepper. A crowd of approximately 250 locals began pelting the party with stones before retreating to the plot of Widow Ryan where a barricade had been built. Ryan owed 40 shillings in arrears and the party advanced to collect either the money or produce of equal value. The Riot Act was read and the soldiers advanced but were beaten back by “spades, sticks, and stones” and sustained injuries for 45 minutes. Waller ordered them to open fire. Nine were killed at the scene and 45 injured, with at least 3 dying later from their wounds. None of the distraining party or escort were killed, though many were injured by rocks, cudgels and pikes. The crowd dispersed, and Ryan paid her tithe.

The conflict had the support of the Roman Catholic clergy, and a letter written by the Bishop of Kildare became the rallying cry:

There are many noble traits in the Irish character, mixed with failings which have always raised obstacles to their own well-being; but an innate love of justice, and an indomitable hatred of oppression, is like a gem upon the front of our nation which no darkness can obscure. To this fine quality I trace their hatred of tithes; may it be as lasting as their love of justice!

Things seem to have been more quiet in Ballynona North, Dungourney, where Michael was growing up. According to Lewis’ A Topological Map of Ireland (1837),

DUNGOURNEY, a parish, partly in the barony of Imokilly, but chiefly in that of Barrymore, county of Cork, and province of Munster, 4½ miles (N.) from Castlemartyr, on the road from Cork to Youghal; containing 2640 inhabitants. This parish comprises 8991 statute acres, of which 5925 are applotted under the tithe act, and valued at £4529 per annum; about 70 acres are woodland, nearly one-fourth of the land is waste, and the remainder is arable and pasture. The soil is generally good, but the system of agriculture is in an unimproved state; there are some quarries of common red stone, which is worked for various purposes, and there is a moderate supply of turf for fuel. The Dungourney river rises in the neighbouring hills of Clonmult, and flows through a deep glen in the parish, assuming near the church a very romantic appearance, and towards the southern boundary adding much beauty to the highly cultivated and richly wooded demesne of Brookdale, the seat of A. Ormsby, Esq. The other seats are Ballynona, that of R. Wigmore, Esq.; Ballynona Cottage, of H, Wigmore, Esq.; and Young Grove, of C.

The current Ballynona House was built around 1900 and serves as a Bed & Breakfast. A number of Millerick descendants have stayed there.

When Michael was nine, the potato blight struck the crops throughout Ireland and An Gort Mor (The Great Famine) began. Not a single district in the country was unscathed. In Castlemartyr (the town nearest Ballynona North), the baptismal figures prior to the famine indicate a young and expanding population with an average of 238 baptisms per year in the 1830s. After the Famine, that dropped to 100, and, by the 1880s, the average was 60 per annum. Similarly, the effects of starvation and emigration in the area can be detected in the marriage records. In the years up to and including 1844, there were an average of 55 marriages per year in the parish. In the decade immediately after 1847, the figure had been halved, and, by the late 19th century, the figures had dropped still further to an all-time low of two weddings for the parish of Imogeela in the year 1888. Ballynona South landlord Henry Wigmore did what he could to help his tenants. He reduced rents and allowed them to keep some of the excess grain. For his kindnesses, he went bankrupt and lost his estate in 1854.

The family survived and did not appear to lose any of the children, but their father, John, seems to have died around 1848, when Michael was only 12 years old. By 1853, there were three Millericks in Ballynona North, all renting from John Courtney —Michael, Jeremiah, and Mary. Michael was renting 63 acres in Section 4 and he was living in house A. Next door on one side, Jeremiah was renting 83 acres in section 5 (house A), and, on other side, Mary was renting 53 acres in section 6 (house A). Mary’s second house was unoccupied, but it had been rented by a Pat Connell—possibly her brother—in 1847. The House Books for Ballynona North in 183 still show John Millerick’s name as the renter, so this Mary was almost defintely the mother of our Michael. According to the Tithe Applotments, the land was being rented to William Millerick in 1824 by Robert Courtney. William was Jeremiah’s father and likely to have been Michael’s grandfather, but the latter has not been proven. The Griffith’s Valuation House Books show Jeremih’s name written above a crossed-out William, who was in turn written above a crossed-out Darby Millerick. Jeremiah had sons named William, John, and Patrick, and this may be the source of the names of the “missing brothers.”

In the mid-1850s, the Potato Blight returned, though not as virulently as before. By 1857, it was clear that the future in Ballynona North was bleak. Michael and two of his sisters—Bridget and Johannah—boarded the ship John Bright, bound for America. They arrived in New York on April 24, 1858, and then made their way to Connecticut. The 1860 US Census lists them in Hartford County, Connecticut, where Michael was a farmhand on the Goodrich farm in Rocky Hill and Bridget was a servant on the Wolcott farm in Wethersfield. Johannah, who went by Hannah, is not in the Census and seems to have married Tom Healion about this time. It is unknown when Michael’s mother and the other four siblings came over, but Ellen’s 1900 Census record indicates they came in 1861. No ship’s manifest has been found, though.

The one Connecticut newspaper reference for Michael is from the Hartford Courant, 3 Feb 1863, when he was arrested with his friend Mike Ryan for “breech of the peace.” They were fined $2 each, which they paid. Around this time, the family decided to immigrate to California. The Civil War had been going for over a year, and conscription was about to be implemented in the North. Bridget and Hannah had both married and each given birth to her first child. California must have seemed a safer place to raise a family. Descendants were told they had come west to search for gold, but this seems a little unlikely as the Rush had been over for more than a decade and there had been no miners in the family. They decided to take two different routes, with the men going overland and the women and children taking a ship around Cape Horn. On board, the sisters befriended a fellow Irishwoman named Mary Taaffe and told her about their handsome brother to whom they would introduce her in California.

In the mid-1850s, the Potato Blight returned, though not as virulently as before. By 1857, it was clear that the future in Ballynona North was bleak. Michael and two of his sisters—Bridget and Johannah—boarded the ship John Bright, bound for America. They arrived in New York on April 24, 1858, and then made their way to Connecticut. The 1860 US Census lists them in Hartford County, Connecticut, where Michael was a farmhand on the Goodrich farm in Rocky Hill and Bridget was a servant on the Wolcott farm in Wethersfield. Johannah, who went by Hannah, is not in the Census and seems to have married Tom Healion about this time. It is unknown when Michael’s mother and the other four siblings came over, but Ellen’s 1900 Census record indicates they came in 1861. No ship’s manifest has been found, though.

The one Connecticut newspaper reference for Michael is from the Hartford Courant, 3 Feb 1863, when he was arrested with his friend Mike Ryan for “breech of the peace.” They were fined $2 each, which they paid. Around this time, the family decided to immigrate to California. The Civil War had been going for over a year, and conscription was about to be implemented in the North. Bridget and Hannah had both married and each given birth to her first child. California must have seemed a safer place to raise a family. Descendants were told they had come west to search for gold, but this seems a little unlikely as the Rush had been over for more than a decade and there had been no miners in the family. They decided to take two different routes, with the men going overland and the women and children taking a ship around Cape Horn. On board, the sisters befriended a fellow Irishwoman named Mary Taaffe and told her about their handsome brother to whom they would introduce her in California.

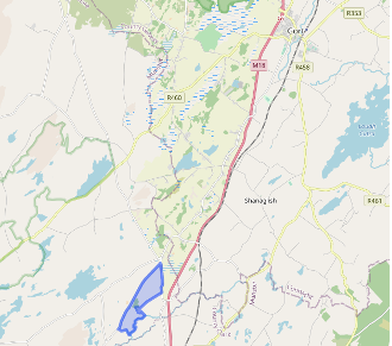

Mary Taaffe was the eldest of three daughters born to George Taaffe, Jr., and Mary Murphy. She was born in 1841 in Shanballysallagh (“the old muddy homestead”), just southwest of the town of Tubber on the Clare-Galway border. The family name is actually Welsh and is a derivative of the personal name David. The Taaffes came to Ireland with the Norman army in 1169 and were initially found in County Louth. How they got to Kilkeedy Parish, County Clare, is unknown.

Clare was a difficult place even before the Famine. Never having great soil for farming, the land was overcrowded with more than 280,000 people. The Napoleonic Wars had brought some economic prosperity because of the demand for supplies. As usual, a depression followed the end of the war. Unemployment in Clare was rampant and prices for crops dropped while rents remained at the wartime high. Famine status was reached at least four times between 1820 and 1835. Many men joined a secret society known as the Terry Alts that terrorized the landowners in the hopes of getting fair rents. In 1931, there were 19 murders in one month. 119 men were arrested, and 21 were hanged. The rest were transported to the Penal Colonies in Australia. There was no land reform, though unemployment was somewhat addressed by building and road projects. Then the Great Famine happened.

In 1841, when Mary was born, Kilkeedy Parish had almost 4000 people. By 1951, that number had dropped to 2100. In Griffith’s Valuation of 1853, there were only two Taaffes in the whole parish and none in Shanballysallagh. George appears to have died. Where his wife and daughters went is unknown, though Mary Murphy had a brother named Patrick who might have taken them in. The fates of the two sisters, Bridget and Ann, are completely unknown. The next reference we have to Mary is as a passenger aboard the SS Edinburgh.

Mary entered New York Harbor on September 29, 1860, and headed to Hartford, where she was hired by the Knapp family as a nanny. There were two Knapp families with children in Hartford in 1960. Edwin Knapp had a nine-year-old son and an infant daughter. John D Knapp had four daughters and a niece, ages 11 to 1. It likely was the JD Knapp family that hired Mary. Years later, Mary told her daughter Annie that the job was difficult because the children were unruly and rude to her. Mary decided to quit her job and seek new employment in the West.

The Healion family gives a good timeline for the cross-country travel. The oldest daughter, Maria, was born in November 11, 1862, in Hartford. Their second child, Julia, was born in 1864 in California. With Michael’s newspaper reference, it seems likely that the Millericks traveled during the Spring or Summer of 1963, though there is some evidence that Tom Healion may have gone to California the previous summer. Family lore says that the men came overland and the women came by ship, but it might not have been that simple. There is some evidence that Kate Millerick came overland and that Philip did not come west until after the Transcontinental Railroad was complete.

The most likely land route was on the Overland Trail. The Overland Trail followed the historic Ben Holladay route along several well-travelled rivers, including the Big Blue River in Nebraska, the Platte in Nebraska and Wyoming, the Sweetwater and Green Rivers in Wyoming, the Great Salt Lake in Utah, and the Thousand Springs Valley and Humboldt Rivers in Nevada. The Overland Trail overlapped with the old Oregon Trail. Those that could walk on the Trail did so to avoid weighing down the wagons, which required constant maintenance to fix wheels, axles, and tarps. Wooden wheels expanded or contracted in extreme weather, causing more headaches. Indian attacks were few in comparison to what later settlers experienced since the wagon trains were only passing through. There were several Pony Express stations along the way, which could serve as rest and repair stops. Trips lasted around five to six months, with wagon trains leaving late enough in the year for the grasses on the Plains to feed their draft animals, and early enough (hopefully) to avoid winter storms in the Cascades and the Sierras. The Sierras can experience dramatic weather fluctuations regardless of season as storms from the Pacific collide with the mountains. Kate Millerick Carsin used to tell her grandchildren stories about crossing the High Desert of Utah, so she may have been with the wagon train instead of on the ship.

During that same spring and summer, 1863, the George Hamrick family crossed the plains and he kept a journal, which was published as “The Overland Trail Journal of an American Emigrant and His Family.” It can be found at http://www.ronsattic.com/journal.htm, and it gives a good account of a 28-wagon train that left Missouri in April and arrived at in California of August in 1863. The advertising summary said,

Accidental shootings! Broken ox wagons! Indians on the trail! Bad water! Crippling wagon wheels! Mountain fever! Abandoned children! Lost cattle! Baby's Born! Beautiful scenery! Triumph at the End of the trail! All this and more in George's Journal from the Trail!

Their trip would have been very similar to that taken by the Millericks.

The trip around the Horn took even longer than the trip overland. The 16,000-mile trip usually took an average of 120 days. The fastest trip was made in 89 days and 13 hours by the Flying Cloud. The trip could be shortened by getting off the ship in Panama, going overland and catching another ship on the other side, but that cost twice as much money as the longer version. A good description of the trip can be found in Boston to San Francisco in Winter of 1862-1863, by A. N. Drown. (A pdf is downloadable at https://archive.org/details/bostontosanfranc00drow.) What stands out is how boring the trip was. On Day 6 already, Drown says, “I am so tired of doing nothing, or rather of doing nothing but read and sit about.” Dealing with the storms around Tierra del Fuego was more exciting—and terrifying—but, for the most part, there was a lot of waiting. On the ship, Mary Taaffe met some of the Millerick sisters. They told her about a brother to whom they wished to introduce her.

Finally, both parties reached California, and Mary and Michael met. They knew each other for as much as four years before they married. Where exactly they were, what they did, and whether they were together or apart during those years is completely unknown. They finally married in May 11, 1868, at St. Vincent’s Church in Petaluma. Michael’s sister Ellen was the maid-of-honor and her brother-in-law Daniel O’Keefe was the best man. One week earlier, Kate Millerick had married John Carsin at St. Vincent’s.

Michael and Mary’s family began to grow. They had a son, John Francis (named after Michael’s father), on February 22, 1869, on Dutton Island near Petaluma. Their second son, George Michael (named after Mary’s father), was born in Petaluma on May 4, 1870.

By 1870, the siblings were beginning to scatter a little bit. According to the 1870 US Census, Michael was living in Vallejo Township, Petaluma, with his wife, their first two children, and both his mother and mother-in-law. When the two Marys (nee Connell and nee Murphy) came to America is unknown, but they were with their children by 1870. Bridget and the Murphy family lived on the next farm over in Petaluma. Kate and John Carsin were in Salt Point near Table Mountain, and Hannah and Tom Healion were in Nicasio. Mary and James O’Keefe were in Sacramento and their niece Maria Healion was living with them and going to school. Philip may have been back East at school, studying to be a priest. There was a Philip Millerick of the right age in the Census at a boarding school, likely St. Mary’s College and Seminary in Ellicott City, Maryland. Ellen could not be found in the Census, but she would marry Patrick Henley in Petaluma that December, so she was likely living in town. The Census also showed that, while Mary Taaffe Millerick could read, she could not write. She likely learned to write as her children learned to write. Michael could both read and write and their mothers could do neither.

The new year of 1871 saw three changes for the family. Early in the year, Michael moved the family to Salt Point, where his sister Kate Carsin was living. His mother stayed in Olema with Hannah. Salt Point is about 4 miles north of Fort Ross, and it had been a center for lumber operations. In the 1850s, Hedley and Sam Duncan had a lumber mill in Salt Point. Another one had opened at Timber Cove in 1860, but it burned down in 1864. After that, Alexander Duncan moved his mill down to Duncans Mill on the Russian River, but Timber Cove and Salt Point still had coves that served as shipping points for the lumber industry.

Salt Point, also known as Louisville, is described in Lynn Hay Rudy’s The Old Salt Point Township in the following way:

This bare and windswept peninsula acknowledges the rocky mineral pools of great value to the native Kashaya. The “town” laid out there in 1871 was named for the Kentucky city were one of the investors had lived…

About 1870, Salt Point began to come back to life again when the Alaska Fur Company, tanning and fur entrepreneurs, bought the land grant from [Alexander] Duncan for $15,780. The new owners, Frederick Funcke, A Wasserman, Louis Sloss, and Louis Gerstle planned to harvest tan oak for their leather processing operation in San Francisco…

The investors also plotted a town, Louisville, whose straight streets were laid out over the narrow bumpy terrace with no regard for the buildings already there. None of their roads were ever built; even the town name did not last. It is not certain why they made the effort to set it up. But a village grew up along Miller’s horse railroad, as loggers and laborers swarmed in during the early 1870s. Brothers William and Walter Dibble ran a general store. Grocer F Helmke of Fisks Mill, a blacksmith, and a butcher (DH Jewell) were among the small tradesmen established there.

Funke and Wasserman built a hotel as part of their new settlement of Louisville, not long after 1871. An ad in Paulson’s Handbook calls it the “largest hotel on the coast” and places it on the stagecoach itinerary.

The Millericks were among those Anglos that “swarmed in” for the economic opportunities. According to his daughter Annie, Michael went to work for the lumber companies in tanning and cordwood for the next five years or so years. Later, he would switch to dairy farming. He worked in Salt Point, Stewart’s Point, Valley Ford, and Cazadero, among other places.

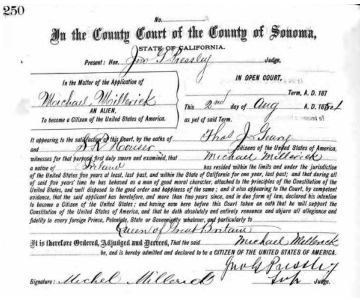

The second change occurred in 1871 when Michael traveled back down to Petaluma where, on August 16, 1871, he renounced his allegiance to Queen Victoria and became a naturalized US citizen. He voted in all elections after that and appeared in The Great Register of California Voters, usually listing his home as Salt Point. Unfortunately, he did not survive into the late 1890s when a physical description would have been given. If his sons were anything like him, though, he would have been about 5’9” with brown hair, a fair complexion, and either hazel or blue eyes.

The third change was the birth of the Millerick’s third child and first daughter Mary Agnes, called Mame, who was born on August 1st. It is unclear whether Mame was born in Salt Point or Cazadero. The birth may even have been in Petaluma as she was baptized by the same priest as her older brothers. Or perhaps the family traveled back to Petaluma for the baptism. Her sister Ellen was born in Cazadero, according to her obituary. Cazadero was not even known as “Cazadero” back then, but was called Austin, after the creek that had carved out the valley. The town was a hunting resort bought by Silas Ingram in 1869. He tried to name it Ingrams, but the federal government named the post office Austin. It was finally renamed Ingrams in 1886 after Silas convinced the Northern Pacific Railroad to extend the line from Duncans Mills. But then George Simpson Montgomery, a wealthy businessman from San Francisco, purchased the town in January 1888 and changed its name to "Cazadero" (Spanish for "The Hunting Place").

The family did not stay in Cazadero for long. Paulson’s Directory of 1874 listed “M Milrick” in Stewarts Point as a general farmer who also sold butter. Hannah, who was always known as Annie, was mostly likely born there in 1874. The next child, Philip, was born in 1875, but it is not known exactly where (possibly Valley Ford). The priests who baptized Annie and Philip, Fr. Clary and Fr. Cullen, were not the same as those who baptized any of their siblings. The closest Catholic Church at the time was in Bodega, a day’s ride away.

Lynn Hay Rudy’s The Old Salt Point Township is an excellent resource for a description of farm life. Suffice it to say that it was hard work with little free time, and the geography of the area could be isolating. An effort was made to create social experiences. There were work-related social occasions, like barn-raisings, quilting and pig scalding (an alternative way to skin the butcher animal). One of the most common social occasions was the family picnic, especially at the beach, where the children could play in the water and build sand castles. It was common enough that the food was never described in the social papers because “everyone knows what a picnic lunch is like.” One wonders if the Millerick Family Picnic has its source here.

Clare was a difficult place even before the Famine. Never having great soil for farming, the land was overcrowded with more than 280,000 people. The Napoleonic Wars had brought some economic prosperity because of the demand for supplies. As usual, a depression followed the end of the war. Unemployment in Clare was rampant and prices for crops dropped while rents remained at the wartime high. Famine status was reached at least four times between 1820 and 1835. Many men joined a secret society known as the Terry Alts that terrorized the landowners in the hopes of getting fair rents. In 1931, there were 19 murders in one month. 119 men were arrested, and 21 were hanged. The rest were transported to the Penal Colonies in Australia. There was no land reform, though unemployment was somewhat addressed by building and road projects. Then the Great Famine happened.

In 1841, when Mary was born, Kilkeedy Parish had almost 4000 people. By 1951, that number had dropped to 2100. In Griffith’s Valuation of 1853, there were only two Taaffes in the whole parish and none in Shanballysallagh. George appears to have died. Where his wife and daughters went is unknown, though Mary Murphy had a brother named Patrick who might have taken them in. The fates of the two sisters, Bridget and Ann, are completely unknown. The next reference we have to Mary is as a passenger aboard the SS Edinburgh.

Mary entered New York Harbor on September 29, 1860, and headed to Hartford, where she was hired by the Knapp family as a nanny. There were two Knapp families with children in Hartford in 1960. Edwin Knapp had a nine-year-old son and an infant daughter. John D Knapp had four daughters and a niece, ages 11 to 1. It likely was the JD Knapp family that hired Mary. Years later, Mary told her daughter Annie that the job was difficult because the children were unruly and rude to her. Mary decided to quit her job and seek new employment in the West.

The Healion family gives a good timeline for the cross-country travel. The oldest daughter, Maria, was born in November 11, 1862, in Hartford. Their second child, Julia, was born in 1864 in California. With Michael’s newspaper reference, it seems likely that the Millericks traveled during the Spring or Summer of 1963, though there is some evidence that Tom Healion may have gone to California the previous summer. Family lore says that the men came overland and the women came by ship, but it might not have been that simple. There is some evidence that Kate Millerick came overland and that Philip did not come west until after the Transcontinental Railroad was complete.

The most likely land route was on the Overland Trail. The Overland Trail followed the historic Ben Holladay route along several well-travelled rivers, including the Big Blue River in Nebraska, the Platte in Nebraska and Wyoming, the Sweetwater and Green Rivers in Wyoming, the Great Salt Lake in Utah, and the Thousand Springs Valley and Humboldt Rivers in Nevada. The Overland Trail overlapped with the old Oregon Trail. Those that could walk on the Trail did so to avoid weighing down the wagons, which required constant maintenance to fix wheels, axles, and tarps. Wooden wheels expanded or contracted in extreme weather, causing more headaches. Indian attacks were few in comparison to what later settlers experienced since the wagon trains were only passing through. There were several Pony Express stations along the way, which could serve as rest and repair stops. Trips lasted around five to six months, with wagon trains leaving late enough in the year for the grasses on the Plains to feed their draft animals, and early enough (hopefully) to avoid winter storms in the Cascades and the Sierras. The Sierras can experience dramatic weather fluctuations regardless of season as storms from the Pacific collide with the mountains. Kate Millerick Carsin used to tell her grandchildren stories about crossing the High Desert of Utah, so she may have been with the wagon train instead of on the ship.

During that same spring and summer, 1863, the George Hamrick family crossed the plains and he kept a journal, which was published as “The Overland Trail Journal of an American Emigrant and His Family.” It can be found at http://www.ronsattic.com/journal.htm, and it gives a good account of a 28-wagon train that left Missouri in April and arrived at in California of August in 1863. The advertising summary said,

Accidental shootings! Broken ox wagons! Indians on the trail! Bad water! Crippling wagon wheels! Mountain fever! Abandoned children! Lost cattle! Baby's Born! Beautiful scenery! Triumph at the End of the trail! All this and more in George's Journal from the Trail!

Their trip would have been very similar to that taken by the Millericks.

The trip around the Horn took even longer than the trip overland. The 16,000-mile trip usually took an average of 120 days. The fastest trip was made in 89 days and 13 hours by the Flying Cloud. The trip could be shortened by getting off the ship in Panama, going overland and catching another ship on the other side, but that cost twice as much money as the longer version. A good description of the trip can be found in Boston to San Francisco in Winter of 1862-1863, by A. N. Drown. (A pdf is downloadable at https://archive.org/details/bostontosanfranc00drow.) What stands out is how boring the trip was. On Day 6 already, Drown says, “I am so tired of doing nothing, or rather of doing nothing but read and sit about.” Dealing with the storms around Tierra del Fuego was more exciting—and terrifying—but, for the most part, there was a lot of waiting. On the ship, Mary Taaffe met some of the Millerick sisters. They told her about a brother to whom they wished to introduce her.

Finally, both parties reached California, and Mary and Michael met. They knew each other for as much as four years before they married. Where exactly they were, what they did, and whether they were together or apart during those years is completely unknown. They finally married in May 11, 1868, at St. Vincent’s Church in Petaluma. Michael’s sister Ellen was the maid-of-honor and her brother-in-law Daniel O’Keefe was the best man. One week earlier, Kate Millerick had married John Carsin at St. Vincent’s.

Michael and Mary’s family began to grow. They had a son, John Francis (named after Michael’s father), on February 22, 1869, on Dutton Island near Petaluma. Their second son, George Michael (named after Mary’s father), was born in Petaluma on May 4, 1870.

By 1870, the siblings were beginning to scatter a little bit. According to the 1870 US Census, Michael was living in Vallejo Township, Petaluma, with his wife, their first two children, and both his mother and mother-in-law. When the two Marys (nee Connell and nee Murphy) came to America is unknown, but they were with their children by 1870. Bridget and the Murphy family lived on the next farm over in Petaluma. Kate and John Carsin were in Salt Point near Table Mountain, and Hannah and Tom Healion were in Nicasio. Mary and James O’Keefe were in Sacramento and their niece Maria Healion was living with them and going to school. Philip may have been back East at school, studying to be a priest. There was a Philip Millerick of the right age in the Census at a boarding school, likely St. Mary’s College and Seminary in Ellicott City, Maryland. Ellen could not be found in the Census, but she would marry Patrick Henley in Petaluma that December, so she was likely living in town. The Census also showed that, while Mary Taaffe Millerick could read, she could not write. She likely learned to write as her children learned to write. Michael could both read and write and their mothers could do neither.

The new year of 1871 saw three changes for the family. Early in the year, Michael moved the family to Salt Point, where his sister Kate Carsin was living. His mother stayed in Olema with Hannah. Salt Point is about 4 miles north of Fort Ross, and it had been a center for lumber operations. In the 1850s, Hedley and Sam Duncan had a lumber mill in Salt Point. Another one had opened at Timber Cove in 1860, but it burned down in 1864. After that, Alexander Duncan moved his mill down to Duncans Mill on the Russian River, but Timber Cove and Salt Point still had coves that served as shipping points for the lumber industry.

Salt Point, also known as Louisville, is described in Lynn Hay Rudy’s The Old Salt Point Township in the following way:

This bare and windswept peninsula acknowledges the rocky mineral pools of great value to the native Kashaya. The “town” laid out there in 1871 was named for the Kentucky city were one of the investors had lived…

About 1870, Salt Point began to come back to life again when the Alaska Fur Company, tanning and fur entrepreneurs, bought the land grant from [Alexander] Duncan for $15,780. The new owners, Frederick Funcke, A Wasserman, Louis Sloss, and Louis Gerstle planned to harvest tan oak for their leather processing operation in San Francisco…

The investors also plotted a town, Louisville, whose straight streets were laid out over the narrow bumpy terrace with no regard for the buildings already there. None of their roads were ever built; even the town name did not last. It is not certain why they made the effort to set it up. But a village grew up along Miller’s horse railroad, as loggers and laborers swarmed in during the early 1870s. Brothers William and Walter Dibble ran a general store. Grocer F Helmke of Fisks Mill, a blacksmith, and a butcher (DH Jewell) were among the small tradesmen established there.

Funke and Wasserman built a hotel as part of their new settlement of Louisville, not long after 1871. An ad in Paulson’s Handbook calls it the “largest hotel on the coast” and places it on the stagecoach itinerary.

The Millericks were among those Anglos that “swarmed in” for the economic opportunities. According to his daughter Annie, Michael went to work for the lumber companies in tanning and cordwood for the next five years or so years. Later, he would switch to dairy farming. He worked in Salt Point, Stewart’s Point, Valley Ford, and Cazadero, among other places.

The second change occurred in 1871 when Michael traveled back down to Petaluma where, on August 16, 1871, he renounced his allegiance to Queen Victoria and became a naturalized US citizen. He voted in all elections after that and appeared in The Great Register of California Voters, usually listing his home as Salt Point. Unfortunately, he did not survive into the late 1890s when a physical description would have been given. If his sons were anything like him, though, he would have been about 5’9” with brown hair, a fair complexion, and either hazel or blue eyes.

The third change was the birth of the Millerick’s third child and first daughter Mary Agnes, called Mame, who was born on August 1st. It is unclear whether Mame was born in Salt Point or Cazadero. The birth may even have been in Petaluma as she was baptized by the same priest as her older brothers. Or perhaps the family traveled back to Petaluma for the baptism. Her sister Ellen was born in Cazadero, according to her obituary. Cazadero was not even known as “Cazadero” back then, but was called Austin, after the creek that had carved out the valley. The town was a hunting resort bought by Silas Ingram in 1869. He tried to name it Ingrams, but the federal government named the post office Austin. It was finally renamed Ingrams in 1886 after Silas convinced the Northern Pacific Railroad to extend the line from Duncans Mills. But then George Simpson Montgomery, a wealthy businessman from San Francisco, purchased the town in January 1888 and changed its name to "Cazadero" (Spanish for "The Hunting Place").

The family did not stay in Cazadero for long. Paulson’s Directory of 1874 listed “M Milrick” in Stewarts Point as a general farmer who also sold butter. Hannah, who was always known as Annie, was mostly likely born there in 1874. The next child, Philip, was born in 1875, but it is not known exactly where (possibly Valley Ford). The priests who baptized Annie and Philip, Fr. Clary and Fr. Cullen, were not the same as those who baptized any of their siblings. The closest Catholic Church at the time was in Bodega, a day’s ride away.

Lynn Hay Rudy’s The Old Salt Point Township is an excellent resource for a description of farm life. Suffice it to say that it was hard work with little free time, and the geography of the area could be isolating. An effort was made to create social experiences. There were work-related social occasions, like barn-raisings, quilting and pig scalding (an alternative way to skin the butcher animal). One of the most common social occasions was the family picnic, especially at the beach, where the children could play in the water and build sand castles. It was common enough that the food was never described in the social papers because “everyone knows what a picnic lunch is like.” One wonders if the Millerick Family Picnic has its source here.

The other important community social events, like Independence Day, were celebrated with a parade, horse racing, and a dance. Plantation had a Druids’ Lodge with a dance hall upstairs. No alcohol was allowed inside, but men often had to “go out for fresh air.” Horse racing was very popular among the Irish and Southern settlers and was very competitive. It usually involved heavy wagering. The Petaluma Millericks were well known as a “horsey people” and an Art Rosebaum sports article said of Buster Millerick, “Horses hear him.”

In 1877, Michael’s mother Mary Connell Millerick passed away. She was in Olema at the time and is buried in the Olema Cemetery. Mary’s mother must have also passed away in the 1870s, but no record or grave has been found. There are reports of burials at Salt Point, but no formal cemeteries have been found.

Also, some time in the 1870s, Philip left seminary school for health reasons and came to live with the Millericks. Whether this was his first trip out West or he had come to California in 1863 and went back for school is not known, but he was naturalized in Hartford Connecticut in November of 1868 and lived, according to the 1870 US Census, in Maryland. He would live the rest of his life with Michael’s family. Apparently, he tried to raise turkeys, but the wild animals got them. Philip died “near Duncans Mill,” on April 9, 1880, of consumption. He left land and cash in the amount of $2300 to his nephews, John and George Millerick. According to the Russian River News, “P Henley sued Millerick” over the probate. Which Millerick this was or whether it was over Philip’s will is not known.

On November 3, 1879, Michael traveled to San Francisco, where he went to the land management office and put down $16 to begin the process of homesteading a160-acre ranch near Table Mountain in Ocean Township at Section 35, Township 9 North, Range 12 West. As witnesses, he had his first cousin Michael Joseph Millerick (son of Jeremiah Millerick) and his neighbor Patrick Gibbon. Interestingly, neither of them nor Michael gave any details about house or land improvements, which were supposed to have been made in order for the Homestead Act to apply. In 1884, the homesteading was complete with an additional payment of $184, which included the purchase of 40 more acres in section 27, which was homesteaded by 1887. As his address, Michael listed Timber Cove, likely because it was the closest post office. On the 1879 California Register, he listed his home as Ocean.

Below is the 1898 map of Salt Point, with Michael’s ranch marked in red. In 1898, George still owned the 40 acres in Section 27, but the origin ranch had been sold to HW Hardt and the William Hill Company (when is unknown), and George had bought 160 acres to the east in a less hilly area. Notice that the farm adjacent to George on the west was the Katherine Carsin ranch. The Carsins had been living on the dairy farm since 1870 and had finished their homestead by 1881, meaning they might have bought the property in 1876. Their ranches were two of over one hundred ranches in Salt Point Township alone.

In 1877, Michael’s mother Mary Connell Millerick passed away. She was in Olema at the time and is buried in the Olema Cemetery. Mary’s mother must have also passed away in the 1870s, but no record or grave has been found. There are reports of burials at Salt Point, but no formal cemeteries have been found.

Also, some time in the 1870s, Philip left seminary school for health reasons and came to live with the Millericks. Whether this was his first trip out West or he had come to California in 1863 and went back for school is not known, but he was naturalized in Hartford Connecticut in November of 1868 and lived, according to the 1870 US Census, in Maryland. He would live the rest of his life with Michael’s family. Apparently, he tried to raise turkeys, but the wild animals got them. Philip died “near Duncans Mill,” on April 9, 1880, of consumption. He left land and cash in the amount of $2300 to his nephews, John and George Millerick. According to the Russian River News, “P Henley sued Millerick” over the probate. Which Millerick this was or whether it was over Philip’s will is not known.

On November 3, 1879, Michael traveled to San Francisco, where he went to the land management office and put down $16 to begin the process of homesteading a160-acre ranch near Table Mountain in Ocean Township at Section 35, Township 9 North, Range 12 West. As witnesses, he had his first cousin Michael Joseph Millerick (son of Jeremiah Millerick) and his neighbor Patrick Gibbon. Interestingly, neither of them nor Michael gave any details about house or land improvements, which were supposed to have been made in order for the Homestead Act to apply. In 1884, the homesteading was complete with an additional payment of $184, which included the purchase of 40 more acres in section 27, which was homesteaded by 1887. As his address, Michael listed Timber Cove, likely because it was the closest post office. On the 1879 California Register, he listed his home as Ocean.

Below is the 1898 map of Salt Point, with Michael’s ranch marked in red. In 1898, George still owned the 40 acres in Section 27, but the origin ranch had been sold to HW Hardt and the William Hill Company (when is unknown), and George had bought 160 acres to the east in a less hilly area. Notice that the farm adjacent to George on the west was the Katherine Carsin ranch. The Carsins had been living on the dairy farm since 1870 and had finished their homestead by 1881, meaning they might have bought the property in 1876. Their ranches were two of over one hundred ranches in Salt Point Township alone.

The 1880 Non-Population Census showed that only 5 acres of the land was under tillage. It was a dairy farm, with 12 milk cows and 11 other cows, 5 horses, 5 pigs, and 50 chickens. One hundred eggs were gathered and 2000 pounds of butter had been made on the ranch in 1879, at a value of $510. There must have been a house, as the family lived there with two Irish farm hands, Alex and John Herbert. By comparison, the Carsins, who had had the dairy ranch next door for ten years, had 12 acres of the land under tillage, 47 cows and 25 calves, 20 pigs, and 24 chickens. They had produced 3000 pounds of butter and gathered 50 eggs in 1879.

There were plenty of families in the area and the children would have gone to school at the Creighton Ridge Schoolhouse (formerly the King’s Ridge school). The school was established in 1879 and their uncle John Carsin was the clerk for the school board. John’s daughter Josie would be the teacher in 1908, long after the Millerick children had grown and moved away.

According to Lynn Hay Rudy, after the lumber mills closed down and moved north, the cash crop for dairy farmers was butter because there was not a population to support milk sales. Michael must have expected his new ranch to be the beginning of a sustainable economic endeavor. Even though the homesteading had not been completed, the family moved to a dairy farm in Nicasio by 1883. Most likely, a small operation such as theirs in Salt Point could not compete with the larger farms and dairies when the coastal schooners stopped visiting Salt Point following the move of the lumber mills further north into Mendocino County. It is unknown if the death of Michael’s sister Bridget Murphy in Novato at the end of 1881 played into the decision. They must have rented a local farm, since there is no record of any purchase or homesteading.

Like most small towns, Nicasio was centered on the General Store, which was built in 1867 by landowner and developer William Miller. The store was leased to a number of managers over the years, and the upper floor was used by the Nicasio Grange, No. 155 Patrons of Husbandry. In 1885, the Nicasio Druids Grove No. 42 purchased the entire building, using the top floor as meeting rooms and leasing the store to a series of operators. The store is remembered as the commercial and social hub of the growing town as it sold a large assortment of dry and canned goods, and housed a Wells Fargo office, the post office, and a saloon with large kegs of beer on tap. There was even a bocce ball court on one side of the store that was always swept and ready for players. As a center for West Marin, there was an early push to make Nicasio the county seat, but it lost out to San Raphael because of its remoteness.

There were both better economic conditions and more social opportunities for the children in Marin. The daughters later joked that the family moved around to help them find husbands. As was said in Claire Villa’s book:

The children were enrolled in the one-room Nicasio School. It must have been a happy time in their lives. In later years, several of the children, Annie and John in particular, revisited the area to see the old school, which had become a landmark. It was a six-mile walk from their home to the school but four or five of the Millerick children were school age at the time so they had plenty of company to walk with and friendly neighbors to greet along the way. The school teacher lived with the family for a time. In those days, this was quite an honor for the family.

The youngest of Michael and Mary’s children was born that year as Margaret joined the family on December 29, 1883. Her godparents were her cousins William and Julia Healion. Just as the Carsins were close in Cazadero, the Healions were just ten miles away from Nicasio in Olema. Again, from Claire’s book:

The Millerick and Healion families were close in those days. Many years later, Annie recalled Christmas spent with the Healions. It must have been quite a trip. She remembered that the roads were poor at best, but they were even worse in the winter. When you visited someone, it took several days—a day to get there, a day or so to visit and celebrate the occasion (Christmas or, perhaps, a christening), and a day to return home. Imagine doing all this with ten children and a horse and buggy!

While they were in Nicasio, Gregory Millerick’s son Jeremiah lived with them and worked on the ranch as a farm hand. He was one of the Petaluma Millericks, a cousin, but it is not known what the exact relationship to Michael was.

Surprisingly, the family did not stay all that long in Nicasio. Michael may have heard about an opportunity in Solano County from the wife of his cousin, the other Michael Millerick. The timing coincided with the death of Bridget’s husband James Murphy and the struggle of his children to get released from their being tied to his dairy farm in Novato. Whether that had an affect or not is unknown.

Michael’s family moved to Grizzley Island, Solano County, in 1887. Grizzley Island was just across the Montezuma Slough from Birds Landing and the Montezuma Hills. On the island, their second daughter, Ellen (known as Nellie), fell in love with and married a handsome young rancher named John Callaghan. The Callaghans owned 1210 acres just east of Birds Landing. To compare to the Millerick’s dairy farm in Salt Point, his future in-law Michael Callaghan’s 160-acre ranch, which was a wheat and sheep ranch that had been in operation for 3 years by the time of the 1870 Non-Population Census, brought in a crop of 25 tons of hay and 1,000 bushels of wheat worth $1,000. They also had two horses and two milch cows, but he had not gotten any pigs or sheep yet. Ten years later, the Callaghans had added another 160 acres, a dozen sheep, two more cows that produced 250 pounds of butter, 40 chickens that produced 200 eggs, and 20 swine.

There are clear similarities between a dairy farm and a wheat ranch. Alan Freese, the grandson of the owner of the Sullivan ranch in the Montezuma Hills, said that all the old ranches had cows, chickens, and horses, as well as raising grain. Because of the need for feed for the animals, all ranches had to do some cultivation of the land. Dairy ranchers tended to cultivate less land and tended to allow their cattle to roam free in the fields. Wheat ranchers cultivated more land and had a few cows for self-sufficiency, but kept them penned to preserve the crops. Excess production on either kind of ranch would be traded for needs with neighbors. For instance, the Millericks might provide milk and/or butter to wheat farmers in exchange for alfalfa for their cows. The Callaghans might provide grain or fleeces in exchange for the loan of horses during the harvest. Often the local general store served as the place of exchange, giving credit until whichever crop or production came in.

Nellie and John were married on September 3, 1890, at St. Joseph’s Church in Rio Vista. The headline of the newly published River News read, “A Society Event in the Shape of a Wedding.” John’s brother Jim served as best man and Ellen’s sister Mame was maid-of-honor. The article even included a list of some of the wedding gifts. Michael and Mary gave them a set of oil paintings and a silver butter dish and knife. Mame gave them an album and a spoon holder, and Miss Ellen O’Keefe gave them a “handsome lamp.”

While in Solano, Annie finished school at the Denverton school district and went on her own overnight to Fairfield to take the exam to qualify as a teacher. Michael was planning to move the family yet again, this time to San Francisco where he would give up farming and decided to “make a go of it” as a laborer. According to an October 3, 1890, article in the River News, Ellen “spent a few days last week with her parents in Denverton, who were on the eve of moving to San Francisco.” Initially, they lived to 726 Fulton, and John and George got jobs as a carpenter and teamster, respectively, and Michael worked as a laborer. There were still active farms in the City, and, into the 20th century, Bernal Heights still had cows and goats. After establishing themselves, the family bought a house at 385 Gates Street, as well as the lots on either side of it and four more lots two blocks further down the hill. Michael and Mary had a new house built at 508 (later 512) Gates. The water was turned on at the new house on December 21, 1891.

There were plenty of families in the area and the children would have gone to school at the Creighton Ridge Schoolhouse (formerly the King’s Ridge school). The school was established in 1879 and their uncle John Carsin was the clerk for the school board. John’s daughter Josie would be the teacher in 1908, long after the Millerick children had grown and moved away.

According to Lynn Hay Rudy, after the lumber mills closed down and moved north, the cash crop for dairy farmers was butter because there was not a population to support milk sales. Michael must have expected his new ranch to be the beginning of a sustainable economic endeavor. Even though the homesteading had not been completed, the family moved to a dairy farm in Nicasio by 1883. Most likely, a small operation such as theirs in Salt Point could not compete with the larger farms and dairies when the coastal schooners stopped visiting Salt Point following the move of the lumber mills further north into Mendocino County. It is unknown if the death of Michael’s sister Bridget Murphy in Novato at the end of 1881 played into the decision. They must have rented a local farm, since there is no record of any purchase or homesteading.

Like most small towns, Nicasio was centered on the General Store, which was built in 1867 by landowner and developer William Miller. The store was leased to a number of managers over the years, and the upper floor was used by the Nicasio Grange, No. 155 Patrons of Husbandry. In 1885, the Nicasio Druids Grove No. 42 purchased the entire building, using the top floor as meeting rooms and leasing the store to a series of operators. The store is remembered as the commercial and social hub of the growing town as it sold a large assortment of dry and canned goods, and housed a Wells Fargo office, the post office, and a saloon with large kegs of beer on tap. There was even a bocce ball court on one side of the store that was always swept and ready for players. As a center for West Marin, there was an early push to make Nicasio the county seat, but it lost out to San Raphael because of its remoteness.

There were both better economic conditions and more social opportunities for the children in Marin. The daughters later joked that the family moved around to help them find husbands. As was said in Claire Villa’s book:

The children were enrolled in the one-room Nicasio School. It must have been a happy time in their lives. In later years, several of the children, Annie and John in particular, revisited the area to see the old school, which had become a landmark. It was a six-mile walk from their home to the school but four or five of the Millerick children were school age at the time so they had plenty of company to walk with and friendly neighbors to greet along the way. The school teacher lived with the family for a time. In those days, this was quite an honor for the family.

The youngest of Michael and Mary’s children was born that year as Margaret joined the family on December 29, 1883. Her godparents were her cousins William and Julia Healion. Just as the Carsins were close in Cazadero, the Healions were just ten miles away from Nicasio in Olema. Again, from Claire’s book:

The Millerick and Healion families were close in those days. Many years later, Annie recalled Christmas spent with the Healions. It must have been quite a trip. She remembered that the roads were poor at best, but they were even worse in the winter. When you visited someone, it took several days—a day to get there, a day or so to visit and celebrate the occasion (Christmas or, perhaps, a christening), and a day to return home. Imagine doing all this with ten children and a horse and buggy!

While they were in Nicasio, Gregory Millerick’s son Jeremiah lived with them and worked on the ranch as a farm hand. He was one of the Petaluma Millericks, a cousin, but it is not known what the exact relationship to Michael was.

Surprisingly, the family did not stay all that long in Nicasio. Michael may have heard about an opportunity in Solano County from the wife of his cousin, the other Michael Millerick. The timing coincided with the death of Bridget’s husband James Murphy and the struggle of his children to get released from their being tied to his dairy farm in Novato. Whether that had an affect or not is unknown.

Michael’s family moved to Grizzley Island, Solano County, in 1887. Grizzley Island was just across the Montezuma Slough from Birds Landing and the Montezuma Hills. On the island, their second daughter, Ellen (known as Nellie), fell in love with and married a handsome young rancher named John Callaghan. The Callaghans owned 1210 acres just east of Birds Landing. To compare to the Millerick’s dairy farm in Salt Point, his future in-law Michael Callaghan’s 160-acre ranch, which was a wheat and sheep ranch that had been in operation for 3 years by the time of the 1870 Non-Population Census, brought in a crop of 25 tons of hay and 1,000 bushels of wheat worth $1,000. They also had two horses and two milch cows, but he had not gotten any pigs or sheep yet. Ten years later, the Callaghans had added another 160 acres, a dozen sheep, two more cows that produced 250 pounds of butter, 40 chickens that produced 200 eggs, and 20 swine.

There are clear similarities between a dairy farm and a wheat ranch. Alan Freese, the grandson of the owner of the Sullivan ranch in the Montezuma Hills, said that all the old ranches had cows, chickens, and horses, as well as raising grain. Because of the need for feed for the animals, all ranches had to do some cultivation of the land. Dairy ranchers tended to cultivate less land and tended to allow their cattle to roam free in the fields. Wheat ranchers cultivated more land and had a few cows for self-sufficiency, but kept them penned to preserve the crops. Excess production on either kind of ranch would be traded for needs with neighbors. For instance, the Millericks might provide milk and/or butter to wheat farmers in exchange for alfalfa for their cows. The Callaghans might provide grain or fleeces in exchange for the loan of horses during the harvest. Often the local general store served as the place of exchange, giving credit until whichever crop or production came in.

Nellie and John were married on September 3, 1890, at St. Joseph’s Church in Rio Vista. The headline of the newly published River News read, “A Society Event in the Shape of a Wedding.” John’s brother Jim served as best man and Ellen’s sister Mame was maid-of-honor. The article even included a list of some of the wedding gifts. Michael and Mary gave them a set of oil paintings and a silver butter dish and knife. Mame gave them an album and a spoon holder, and Miss Ellen O’Keefe gave them a “handsome lamp.”

While in Solano, Annie finished school at the Denverton school district and went on her own overnight to Fairfield to take the exam to qualify as a teacher. Michael was planning to move the family yet again, this time to San Francisco where he would give up farming and decided to “make a go of it” as a laborer. According to an October 3, 1890, article in the River News, Ellen “spent a few days last week with her parents in Denverton, who were on the eve of moving to San Francisco.” Initially, they lived to 726 Fulton, and John and George got jobs as a carpenter and teamster, respectively, and Michael worked as a laborer. There were still active farms in the City, and, into the 20th century, Bernal Heights still had cows and goats. After establishing themselves, the family bought a house at 385 Gates Street, as well as the lots on either side of it and four more lots two blocks further down the hill. Michael and Mary had a new house built at 508 (later 512) Gates. The water was turned on at the new house on December 21, 1891.

In November of 1891, Michael and Mary became grandparents for the first time. Ellen and John Callaghan had their first daughter, Ruth B. (no one knows what the B. stands for), on November 8th. Ellen came to town to be with her mother and sisters for the birth, and Ruth was born in Bernal Heights at the Gates Street house. Ellen’s other four children would also be born on Gates Street.

Michael and Mary would have 30 grandchildren. Unfortunately, Ruth would be the only one they had the chance to hold. After Nellie and Ruth went back to the ranch near Rio Vista, an influenza epidemic swept through the City, and the new grandparents both became ill. Mary died on December 31, 1891, and Michael died just four days later on January 4, 1892. Mary was only 50 and Michael only 57 years old. The funerals took place at St. Paul’s Church on Church Street, after which they were interred in a newly purchased family plot in Holy Cross Cemetery in Colma.

Michael and Mary would have 30 grandchildren. Unfortunately, Ruth would be the only one they had the chance to hold. After Nellie and Ruth went back to the ranch near Rio Vista, an influenza epidemic swept through the City, and the new grandparents both became ill. Mary died on December 31, 1891, and Michael died just four days later on January 4, 1892. Mary was only 50 and Michael only 57 years old. The funerals took place at St. Paul’s Church on Church Street, after which they were interred in a newly purchased family plot in Holy Cross Cemetery in Colma.

Michael and Mary were a hardworking couple who would do anything for their children. They were flexible and adaptive in their willingness to move on to the next best option. Unfortunately, they seemed to have been burdened with bad timing. They came to America just in time for the Civil War. They went to California too late for the Gold Rush and moved to Northern Sonoma too late for the big Timber Rush. They homesteaded a ranch almost 20 years after the Homestead Act came into law and left the land before the five years needed to establish occupancy. They went to Nicasio in time for a tuberculosis epidemic and came to San Francisco in time for the influenza epidemic that killed them.

But their resilience and strength of will gave their children the foundation needed to make successful lives of their own. Each was successful and they all clung together as a family. Annie became the Grande Dame of the family and began the annual Millerick Family Picnic, which continues today, over 100 years later. Family meant everything to Michael and Mary, and they passed that value down to their descendants.

Post Script: The family always thought of 527 Gates Street as the family home. This house was not built until 1896, when George finally turned on the water. In fact, 385 had been the family home for more Millericks and more years, but they sold it in 1896 after they moved into 527 Gates. And they only lived there for five years, until William sold the house in 1901. Until 2017, no one in the family even knew of the existence of 508 Gates as the house that Michael built. But, the Millericks built well. The houses at 508 (now 512) and 527 (now 559) Gates are the only ones on the block which were built before the Earthquake and still exist.

But their resilience and strength of will gave their children the foundation needed to make successful lives of their own. Each was successful and they all clung together as a family. Annie became the Grande Dame of the family and began the annual Millerick Family Picnic, which continues today, over 100 years later. Family meant everything to Michael and Mary, and they passed that value down to their descendants.

Post Script: The family always thought of 527 Gates Street as the family home. This house was not built until 1896, when George finally turned on the water. In fact, 385 had been the family home for more Millericks and more years, but they sold it in 1896 after they moved into 527 Gates. And they only lived there for five years, until William sold the house in 1901. Until 2017, no one in the family even knew of the existence of 508 Gates as the house that Michael built. But, the Millericks built well. The houses at 508 (now 512) and 527 (now 559) Gates are the only ones on the block which were built before the Earthquake and still exist.