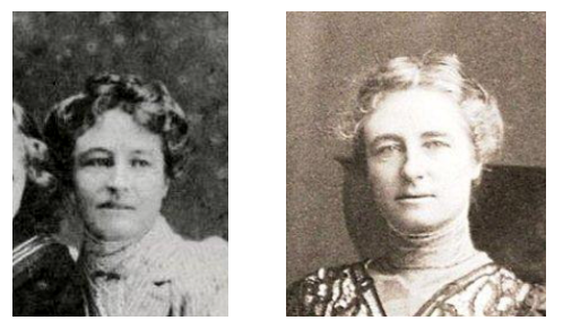

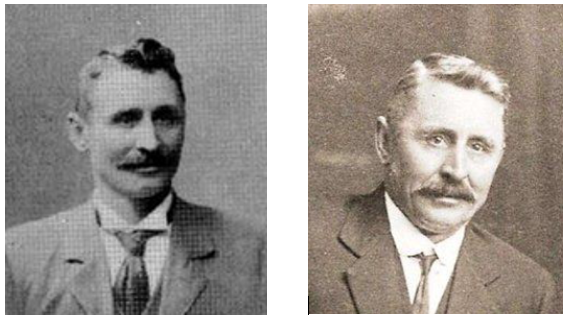

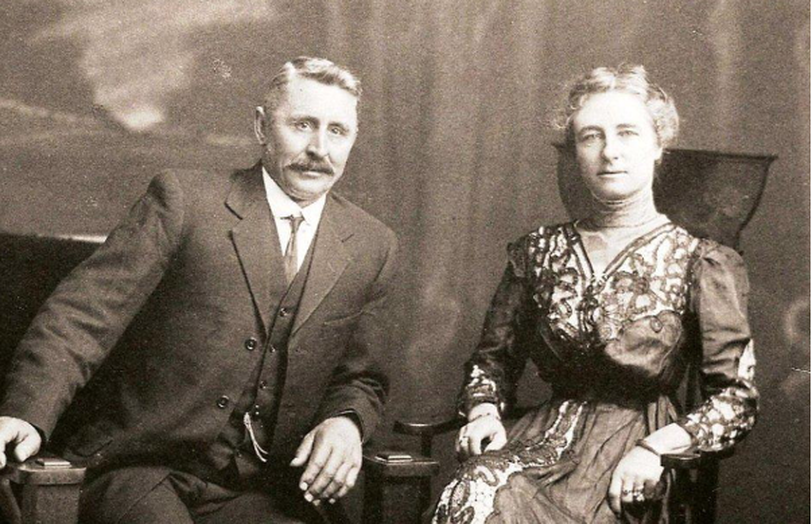

Emily Agnes Callaghan and Arthur Birding

Birth: 12 Oct 1867, Okains Bay, Canterbury, New Zealand

Death: 4 Aug 1943, Totara Valley, Timaru, Canterbury, New Zealand

Burial: Bromley, Christchurch City, Canterbury, New Zealand

Death: 4 Aug 1943, Totara Valley, Timaru, Canterbury, New Zealand

Burial: Bromley, Christchurch City, Canterbury, New Zealand

Spouse: Arthur John Birdling

Birth: 24 Apr 1863, Birdlings Flat, Canterbury, New Zealand

Death: 12 Oct 1962, Halswell, Christchurch City, Canterbury, New Zealand

Father: William Birdling (1822-1902)

Mother: Jane Loveridge (1826-1900)

Marriage: 20 Feb 1890, Christchurch, Canterbury, New Zealand

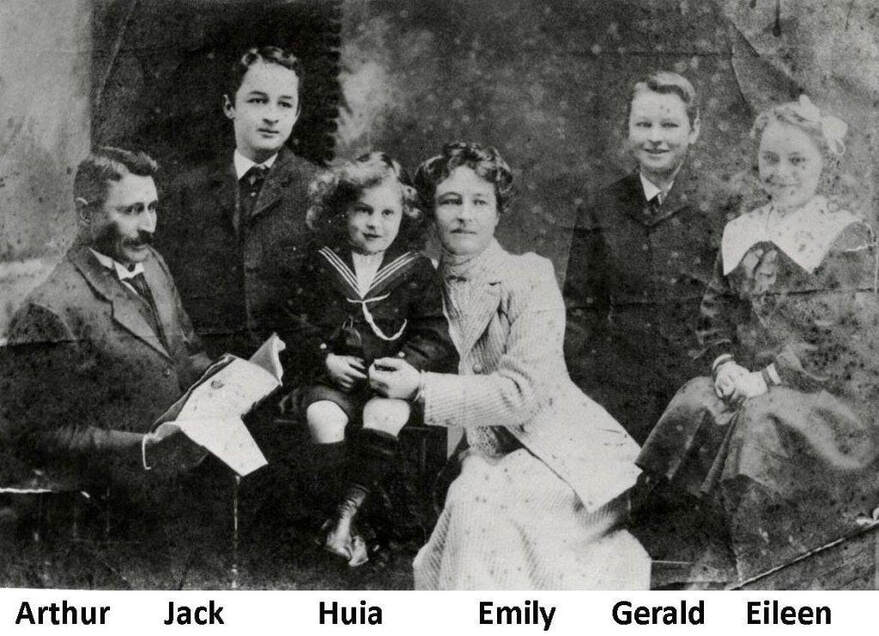

Children: Arthur John (Jack) Ware (1890-1916)

Gerald Edward (1892-1981)

Eileen Anita (1896-1983)

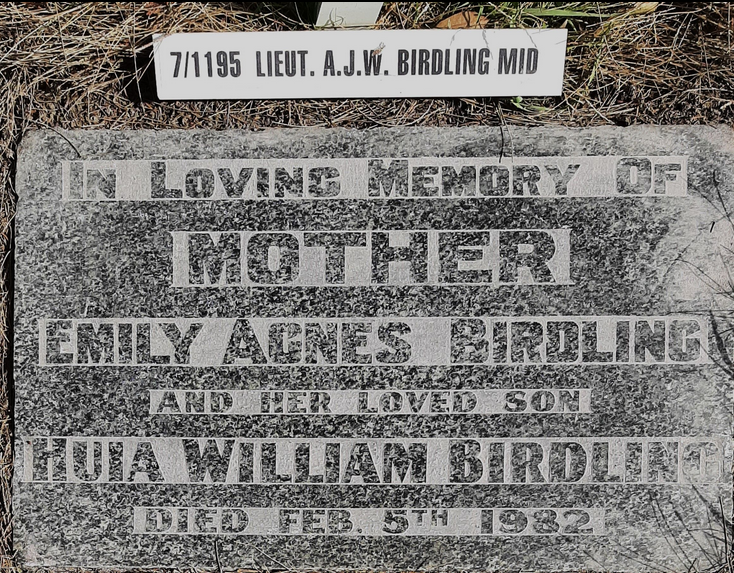

Huia William (1902-1982)

Birth: 24 Apr 1863, Birdlings Flat, Canterbury, New Zealand

Death: 12 Oct 1962, Halswell, Christchurch City, Canterbury, New Zealand

Father: William Birdling (1822-1902)

Mother: Jane Loveridge (1826-1900)

Marriage: 20 Feb 1890, Christchurch, Canterbury, New Zealand

Children: Arthur John (Jack) Ware (1890-1916)

Gerald Edward (1892-1981)

Eileen Anita (1896-1983)

Huia William (1902-1982)

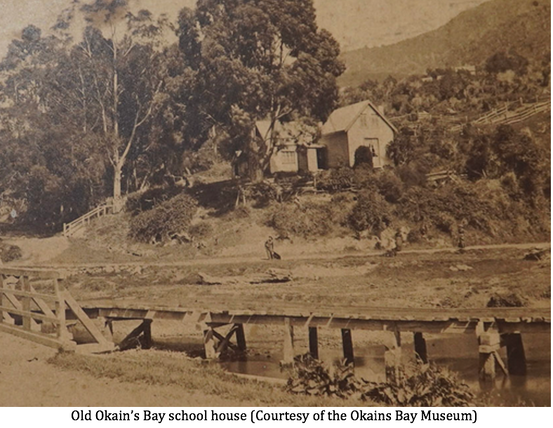

Emily Agnes Callaghan was the only child of Patrick Callaghan and Emma Ware. She was born on October 12, 1867, in Okains Bay, New Zealand. Her father was from Effin, Limerick, and had come to New Zealand by way of South Australia. He settled in Okains Bay and became a cattle rancher. Her mother came to Okains Bay from Devonshire at the age of four with her parents and brother. Her father was a successful millwright and sheep rancher. Emily was baptized into the Roman Catholic faith on November 28, 1867, at the Cathedral of the Blessed Sacrament in Christchurch.

When her mother Emma was growing up, Okains Bay was a pretty wild and wooly place which earned it a reputation that continues until today. Things were more settled during Emily’s childhood. There was a church and a library before she was born. The Okains Bay School opened when Emily was five, and she attended school there. That same year, the road from Akaroa to Christchurch—and its connection to Okains Bay—was completed from a more-or-less bridle path to a full coach road. Her father would drive cattle to market up Old Okains Bay Road to Summit Road and on to Akaroa, a trip of about 11 miles. They likely made frequent trips to Akaroa and attended St. Patrick’s Church there.

Emily was an only child, but she was not completely alone. She was the oldest of 15 cousins, all grandchildren of Thomas Ware and Mary Ann Bond. The closest in age was Thomas ware, who was two years younger than she. But he died at four months. The next closest was Annie Jane Ware, who was five years younger than Emily. The youngest cousin, Freeman Sefton, was the same age as her second son Gerald. Combine the age differences with the fact that she lived on the Ranch up in the hills while the cousins were down in the valley, Emily did grow up in a somewhat isolated manner.

One of Emily’s passions raised its head early in her life: painting. (It was a passion shared by her California cousins Dolores Callaghan Quattrin and Nadine Woods Zlatunich.) In 1877, she came in third in the Okains Bay School in the 3rd grade art contest. In 1883, she won an award Akaroa Horticultural, Industrial, and Pastoral Exhibition for Illumination. According to Akaroa Mail and Banks Peninsula Advertiser,

Miss Emily Callaghan contributed no less than eight drawings of various descriptions, all of them displaying considerable merit and some rising very considerably above mediocrity.”

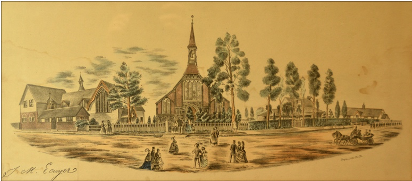

Family lore said that Emily attended the Convent school in Akaroa, but that school did not open until 1898. In fact, she is shown as enrolled in the Convent of the Sacred Heart School in Christchurch in 1882. This later became Catholic Cathedral College. The website (https://www.cathcollege.school.nz/about-us-1/history-tahuhu-korero-1) says:

Catholic Cathedral College is located at the city end of the Ferry Road corridor. In historical times, this was one of many significant travel routes linking permanent or semi-permanent Māori settlements in the now city area, to the Ōpawaho/Heathcote River and adjoining Ihutai/Avon-Heathcote Estuary. The area has a rich history and remains of vital importance for Ngāi Tūāhuriri culture, values and practices including mahinga kai (food gathering) of shellfish, eels, fish, plants and birds. The Ferry Road corridor also linked with the tracks which lay between the largest pā of Ngāi Tahu to the north, in Kaiapoi, to kāinga on Horomaka (Banks Peninsula) and around to Te Waihora (Lake Ellesmere) and the Rāpaki Track, the then principal route from the plains to Whakaraupō (Lyttelton Harbour).

Emily was an only child, but she was not completely alone. She was the oldest of 15 cousins, all grandchildren of Thomas Ware and Mary Ann Bond. The closest in age was Thomas ware, who was two years younger than she. But he died at four months. The next closest was Annie Jane Ware, who was five years younger than Emily. The youngest cousin, Freeman Sefton, was the same age as her second son Gerald. Combine the age differences with the fact that she lived on the Ranch up in the hills while the cousins were down in the valley, Emily did grow up in a somewhat isolated manner.

One of Emily’s passions raised its head early in her life: painting. (It was a passion shared by her California cousins Dolores Callaghan Quattrin and Nadine Woods Zlatunich.) In 1877, she came in third in the Okains Bay School in the 3rd grade art contest. In 1883, she won an award Akaroa Horticultural, Industrial, and Pastoral Exhibition for Illumination. According to Akaroa Mail and Banks Peninsula Advertiser,

Miss Emily Callaghan contributed no less than eight drawings of various descriptions, all of them displaying considerable merit and some rising very considerably above mediocrity.”

Family lore said that Emily attended the Convent school in Akaroa, but that school did not open until 1898. In fact, she is shown as enrolled in the Convent of the Sacred Heart School in Christchurch in 1882. This later became Catholic Cathedral College. The website (https://www.cathcollege.school.nz/about-us-1/history-tahuhu-korero-1) says:

Catholic Cathedral College is located at the city end of the Ferry Road corridor. In historical times, this was one of many significant travel routes linking permanent or semi-permanent Māori settlements in the now city area, to the Ōpawaho/Heathcote River and adjoining Ihutai/Avon-Heathcote Estuary. The area has a rich history and remains of vital importance for Ngāi Tūāhuriri culture, values and practices including mahinga kai (food gathering) of shellfish, eels, fish, plants and birds. The Ferry Road corridor also linked with the tracks which lay between the largest pā of Ngāi Tahu to the north, in Kaiapoi, to kāinga on Horomaka (Banks Peninsula) and around to Te Waihora (Lake Ellesmere) and the Rāpaki Track, the then principal route from the plains to Whakaraupō (Lyttelton Harbour).

Although the Barbadoes Street/Ferry Road site is the historical home of Catholic education in Christchurch, the very first Catholic school in the city was established by a newly arrived young Irishman, Mr. Edward O’Connor who on May 3rd 1865, opened the first Catholic school in Christchurch in a cottage on Lichfield St with just two pupils. However, money was quickly raised to purchase land on Barbadoes Street next to the Church of the Blessed Sacrament, and the O’Connor school shifted there in October 1865 with 86 pupils.

In 1868, the Sisters of Our Lady of the Missions established the Sacred Heart School for Girls on the Ferry Road side of the Church. In 1880, the first Catholic secondary school for girls, Sacred Heart College, was opened on the same site.

Like the Sacred Heart Girls’ Schools around the world, this new school was a finishing school for the daughters of wealth. According to records in archives of the Sisters of Our Lady of the Missions, “Emily O’Callaghan” of Okains Bay became a boarded student on January 19, 1882, when she was 15 years old. The tuition was £43 per year, “music, singing, and washing included.” There were quite a few extra fees for work clothes and dresses, stationery, sheet music, painting supplies, books, and extra classes like flower arranging and calisthenics. Even a fee for staying during the July holidays the first year.

On December 15, 1882, an awards ceremony and evening of entertainment was held for the students and parents. According to articles in The Globe, The Press, and other papers:

The annual distribution of prizes to the pupils of the Sacred Heart High School took place yesterday afternoon at the Convent, Barbadoes street. The ceremony was preceded by an entertainment, consisting of vocal and instrumental music and recitations given by the pupils of the school. There was a large attendance of the parents and friends of the scholars, and the items on the programme which comprised a number of very pretty pieces, were rendered in a manner which, while testifying to the efficiency of the institution, gave great satisfaction to the audience. The young ladies’ work was exhibited in one of the class rooms, and was much admired by a large number of visitors, who had ample opportunities of judging of the proficiency of the pupils in all the different branches of instruction imparted at the school. Some of the specimens of drawing and painting were particularly commendable, and the needlework was most praiseworthy.

After the entertainment, the awards were presented. Emily captured many prizes. She came in first in Music, Singing, Drawing, Plain and Ornamental Writing, and Fancy Needlework. Her great-granddaughter Juliana said, “I do know she was very prolific in needlework and I have several tablecloths etc that she did.” Emily came in second in Composition and letter writing. She received honorable mention in Painting and in Universal History (as opposed to Bible History). She did similarly well in 1883. On the other hand, she is not mentioned among the prize winners for Exemplary Conduct, Deportment and Politeness, or Punctual Attendance.

After graduation in April of 1884, Emily returned to Okains Bay as a polished lady of society. How that would have juxtaposed with her father’s Limerick brogue and Gaelic profanities is anyone’s guess. But Emily was 17 and ready adult society in Akaroa and Okains Bay. Aside from her religion, she would have been a good match for a Birdling.

In 1868, the Sisters of Our Lady of the Missions established the Sacred Heart School for Girls on the Ferry Road side of the Church. In 1880, the first Catholic secondary school for girls, Sacred Heart College, was opened on the same site.

Like the Sacred Heart Girls’ Schools around the world, this new school was a finishing school for the daughters of wealth. According to records in archives of the Sisters of Our Lady of the Missions, “Emily O’Callaghan” of Okains Bay became a boarded student on January 19, 1882, when she was 15 years old. The tuition was £43 per year, “music, singing, and washing included.” There were quite a few extra fees for work clothes and dresses, stationery, sheet music, painting supplies, books, and extra classes like flower arranging and calisthenics. Even a fee for staying during the July holidays the first year.

On December 15, 1882, an awards ceremony and evening of entertainment was held for the students and parents. According to articles in The Globe, The Press, and other papers:

The annual distribution of prizes to the pupils of the Sacred Heart High School took place yesterday afternoon at the Convent, Barbadoes street. The ceremony was preceded by an entertainment, consisting of vocal and instrumental music and recitations given by the pupils of the school. There was a large attendance of the parents and friends of the scholars, and the items on the programme which comprised a number of very pretty pieces, were rendered in a manner which, while testifying to the efficiency of the institution, gave great satisfaction to the audience. The young ladies’ work was exhibited in one of the class rooms, and was much admired by a large number of visitors, who had ample opportunities of judging of the proficiency of the pupils in all the different branches of instruction imparted at the school. Some of the specimens of drawing and painting were particularly commendable, and the needlework was most praiseworthy.

After the entertainment, the awards were presented. Emily captured many prizes. She came in first in Music, Singing, Drawing, Plain and Ornamental Writing, and Fancy Needlework. Her great-granddaughter Juliana said, “I do know she was very prolific in needlework and I have several tablecloths etc that she did.” Emily came in second in Composition and letter writing. She received honorable mention in Painting and in Universal History (as opposed to Bible History). She did similarly well in 1883. On the other hand, she is not mentioned among the prize winners for Exemplary Conduct, Deportment and Politeness, or Punctual Attendance.

After graduation in April of 1884, Emily returned to Okains Bay as a polished lady of society. How that would have juxtaposed with her father’s Limerick brogue and Gaelic profanities is anyone’s guess. But Emily was 17 and ready adult society in Akaroa and Okains Bay. Aside from her religion, she would have been a good match for a Birdling.

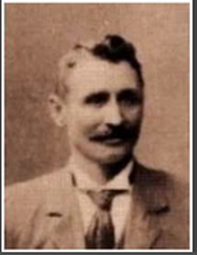

Arthur John Birdling was born on April 24, 1863, in Waikoko Valley, at Birdling’s Flat. He was the sixth child of pioneers William Birdling, a successful sheep farmer from Marston-Bigot, Somerset, England, and Jane Loverage, from Netherbury, West Dorset. William had come to New Zealand in 1842 on the London at the age of 20 with only one sovereign in his pocket. From that beginning, William built a cattle empire of 11,000 acres in Birdling’s Flat, Duvauchelle Bay, Hornby, and Halswell. The family’s original name was Bird (William was the son of Robert Bird and Ann Ashman), but William changed it to Birdling in New Zealand.

In 1843, William Birdling began working as an overseer for Bernard Rhodes on the Akaroa Peninsula. During the first two years, he only earned £20 per year. According to his biography in The Cyclopedia of New Zealand:

In 1852, when, by great self-denial and hard work he had got together a considerable sum of money, Mr. Birdling purchased the first portion of the fine estate now so well known as Birdling's Flat, near Little River. At first, he bought only a small area, but the estate now consists of about 5,000 acres of the choicest and richest land in the district. On this property, as it was increased from time to time, work that was never given up, but was extremely hard and almost herculean, had to be done and was done by Mr Birdling and his family, in order to convert the wilderness of tussock, flax and swamp, into its present state of high cultivation and settled workableness.

http://nzetc.victoria.ac.nz//tm/scholarly/tei-Cyc03Cycl-t1-body1-d6-d7-d3.html#name-422265-mention

In 1843, William Birdling began working as an overseer for Bernard Rhodes on the Akaroa Peninsula. During the first two years, he only earned £20 per year. According to his biography in The Cyclopedia of New Zealand:

In 1852, when, by great self-denial and hard work he had got together a considerable sum of money, Mr. Birdling purchased the first portion of the fine estate now so well known as Birdling's Flat, near Little River. At first, he bought only a small area, but the estate now consists of about 5,000 acres of the choicest and richest land in the district. On this property, as it was increased from time to time, work that was never given up, but was extremely hard and almost herculean, had to be done and was done by Mr Birdling and his family, in order to convert the wilderness of tussock, flax and swamp, into its present state of high cultivation and settled workableness.

http://nzetc.victoria.ac.nz//tm/scholarly/tei-Cyc03Cycl-t1-body1-d6-d7-d3.html#name-422265-mention

Birdling's Flat—originally named Te Mata Hapuku—is at the east end of Kaitorete Spit, close to the shore of Lake Ellesmere. The nearby pebble beach is well known as a place to find small agates and other attractive rounded pebbles. (The local museum is the Birdlings Flat Gemstone and Fossil Museum, where there is a private collection that mainly consists of semi-precious stones and fossils collected over a 50-year period off the beach at Birdlings Flat and other parts of Canterbury.) Hector's dolphins live along the beach in notable numbers, and whales, fur seals, much rarer whales and elephant seals are known to appear. It was a very isolated area and the railroad did not reach there until 1882. The picture below from the Endless video game was created based on Birdling’s Flat. In the Land Notes of the game, Birdling’s Flat is described as

Inspired by a small and isolated coastal settlement in the South Island of New Zealand, Birdlings Flat offers wide vistas, unkempt fields, a pebbled coastline strewn with driftwood, a sprinkling of science, and a chance to find stillness.

Inspired by a small and isolated coastal settlement in the South Island of New Zealand, Birdlings Flat offers wide vistas, unkempt fields, a pebbled coastline strewn with driftwood, a sprinkling of science, and a chance to find stillness.

https://modemworld.me/2022/07/27/an-endless-birdlings-flat-in-second-life/

According to The Cyclopedia of New Zealand, the Birdling’s first house was a simple wattle-and-daub structure with a thatched roof. For thousands of years, houses had been made by putting stakes in the ground, winding branches and saplings (wattle) between them, and smearing mud (daub) over the branches to seal out the wind. Arthur’s oldest brother was born probably there in that house in 1853. A proper stone and wood house would have gone up as soon as the business became profitable. The property was known as Waikoko and would stay in the family for 110 years. The last Birdling to work the farm was Stanley W. Birdling, who had 1450 sheep and 47 head of cattle. The property sold in 1970 for $69,308.

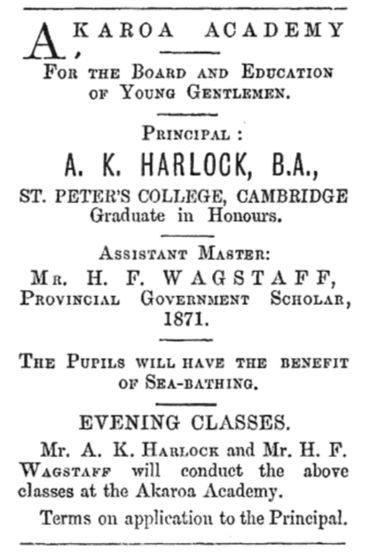

Education was important to the Birdlings. With no schools nearby, one room in their house was dedicated as a school room just for the eight Birdling children, and a private tutor was hired to teach them. Later, Arthur and at least one of his brothers was sent to a private boarding school called the Akaroa Academy, which was established in 1873 and run by Mr. A K Harlock. It is good to know that AJ would have had “the benefit of sea-bathing” at the school.

In 1875, William expanded his enterprises by purchasing 298 acres of land at the head of Robinson Bay. The land included the Onawe Peninsula and the site of the 1838 Maori Massacre. He had a two-story, 12-room house built nearby. He turned the operations of the Birdling’s Flat station over to his two eldest sons and moved the family there by 1877. He became active in the livestock market in Akaroa and would have become acquainted with Emily’s father Patrick Callaghan there. It is likely that Arthur and Emily met as preteens around this time.

In 1881, Arthur was sent to Canterbury Agricultural College, Lincoln, to learn agricultural farming. The school was only in its second year of existence and had 56 students. The director was Mr. W. E. Ivey. According to the 1952 article in The Press, written to commemorate his 89th birthday,

At Lincoln, Mr. Birdling gained his first knowledge of cropping. In his first year at Lincoln, the crops were cut by side delivery, and the harvesters had to tie the sheaves with bands of straw. In his second year, a wire binder was sent to the college, but he did not like it. Mr. Birdling drove the binder into a furrow, and put it out of action. In his final year came the twine binder. The students were paid for their harvesting work at the college. Mr. Birdling gained a diploma at the college, but the document was destroyed in a fire which burnt down his home at “Lansdowne” in 1944. When he was at the college, Mr. Birdling was made a councillor or prefect, a reward for good behavior. He also captained the college Rugby team.

After graduating, Arthur went back to livestock farming.

Emily and Arthur were married on February 20, 1890, at St. John’s Church, Christchurch. The announcement in The Press read:

BIRDLING-CALLAGHAN - On February 20th, at St John's Church, Christchurch, by the Rev J. O'Bryan Hoare, Arthur John, fifth son of William Birdling, Lake View Station, to Emily Agnes, only daughter of P. Callaghan, Duvauchelle's Bay. No cards. No cake.

Like Emily’s parents, Emily and Arthur were not raised in the same faith. Emily was raised Catholic and Arthur Anglican. According to her great granddaughter, Emily left the Church when she married Arthur.

The year before, his father had sold the Onawe property to Emily’s father and went to live at Hornby, where he (William) had 96 acres of freehold land and 40 acres of leasehold. The newlyweds moved into the Hornby property, and William moved to property he owned in Shirley. Hornby is a major suburb of Christchurch, situated on the western edge of the city. At the time when the Birdlings resided there, it was still mostly open farm land. Hornby was originally referred to as Southbridge Junction – with the junction acting as the start of the main road south. Due to rising confusion with the nearby town of Southbridge, a decision was made to rename the area to Hornby in 1878, although the origins of this name are unclear. One explanation holds that the suburb was named after Hornby-with-Farleton in Lancashire by Frederick William Delamain, who came to Christchurch from England in 1852. Delamain owned a nearby homestead and was a prominent figure in the area. Another version suggests that the name refers to Geoffrey Hornby, who was the Admiral of the British flying squadron that visited Christchurch in 1870.

At Hornby, their first child, Arthur John Ware Birdling, was born on November 6, 1890. Known as Jackie, he was everyone’s darling. He was joined two years later by a second son, Gerald Edward, and four years after that by a daughter, Eileen Anita. A final son, Huia William, was born in 1902. There were passings as well. In 1891, Emily’s grandfather Thomas Ware died, followed by her grandmother Mary Ann Bond Ware in 1895. Her other grandfather, John Callaghan, had died in 1890, but she most likely never knew him.

Not only were the Birdlings' lives changing, the world was changing around them. On September 19, 1893, Governor Lord Glasgow signed a new Electoral Act into law, and New Zealand became the first self-governing country in the world to enshrine in law the right for women to vote in parliamentary elections. Thus, Emily became the first Callaghan woman to vote in a government election.

Education was important to the Birdlings. With no schools nearby, one room in their house was dedicated as a school room just for the eight Birdling children, and a private tutor was hired to teach them. Later, Arthur and at least one of his brothers was sent to a private boarding school called the Akaroa Academy, which was established in 1873 and run by Mr. A K Harlock. It is good to know that AJ would have had “the benefit of sea-bathing” at the school.

In 1875, William expanded his enterprises by purchasing 298 acres of land at the head of Robinson Bay. The land included the Onawe Peninsula and the site of the 1838 Maori Massacre. He had a two-story, 12-room house built nearby. He turned the operations of the Birdling’s Flat station over to his two eldest sons and moved the family there by 1877. He became active in the livestock market in Akaroa and would have become acquainted with Emily’s father Patrick Callaghan there. It is likely that Arthur and Emily met as preteens around this time.

In 1881, Arthur was sent to Canterbury Agricultural College, Lincoln, to learn agricultural farming. The school was only in its second year of existence and had 56 students. The director was Mr. W. E. Ivey. According to the 1952 article in The Press, written to commemorate his 89th birthday,

At Lincoln, Mr. Birdling gained his first knowledge of cropping. In his first year at Lincoln, the crops were cut by side delivery, and the harvesters had to tie the sheaves with bands of straw. In his second year, a wire binder was sent to the college, but he did not like it. Mr. Birdling drove the binder into a furrow, and put it out of action. In his final year came the twine binder. The students were paid for their harvesting work at the college. Mr. Birdling gained a diploma at the college, but the document was destroyed in a fire which burnt down his home at “Lansdowne” in 1944. When he was at the college, Mr. Birdling was made a councillor or prefect, a reward for good behavior. He also captained the college Rugby team.

After graduating, Arthur went back to livestock farming.

Emily and Arthur were married on February 20, 1890, at St. John’s Church, Christchurch. The announcement in The Press read:

BIRDLING-CALLAGHAN - On February 20th, at St John's Church, Christchurch, by the Rev J. O'Bryan Hoare, Arthur John, fifth son of William Birdling, Lake View Station, to Emily Agnes, only daughter of P. Callaghan, Duvauchelle's Bay. No cards. No cake.

Like Emily’s parents, Emily and Arthur were not raised in the same faith. Emily was raised Catholic and Arthur Anglican. According to her great granddaughter, Emily left the Church when she married Arthur.

The year before, his father had sold the Onawe property to Emily’s father and went to live at Hornby, where he (William) had 96 acres of freehold land and 40 acres of leasehold. The newlyweds moved into the Hornby property, and William moved to property he owned in Shirley. Hornby is a major suburb of Christchurch, situated on the western edge of the city. At the time when the Birdlings resided there, it was still mostly open farm land. Hornby was originally referred to as Southbridge Junction – with the junction acting as the start of the main road south. Due to rising confusion with the nearby town of Southbridge, a decision was made to rename the area to Hornby in 1878, although the origins of this name are unclear. One explanation holds that the suburb was named after Hornby-with-Farleton in Lancashire by Frederick William Delamain, who came to Christchurch from England in 1852. Delamain owned a nearby homestead and was a prominent figure in the area. Another version suggests that the name refers to Geoffrey Hornby, who was the Admiral of the British flying squadron that visited Christchurch in 1870.

At Hornby, their first child, Arthur John Ware Birdling, was born on November 6, 1890. Known as Jackie, he was everyone’s darling. He was joined two years later by a second son, Gerald Edward, and four years after that by a daughter, Eileen Anita. A final son, Huia William, was born in 1902. There were passings as well. In 1891, Emily’s grandfather Thomas Ware died, followed by her grandmother Mary Ann Bond Ware in 1895. Her other grandfather, John Callaghan, had died in 1890, but she most likely never knew him.

Not only were the Birdlings' lives changing, the world was changing around them. On September 19, 1893, Governor Lord Glasgow signed a new Electoral Act into law, and New Zealand became the first self-governing country in the world to enshrine in law the right for women to vote in parliamentary elections. Thus, Emily became the first Callaghan woman to vote in a government election.

In 1896, William bought the 165-acre the property at Halswell. After he died in 1902, Arthur and Emily moved their family there and would live there for the rest of their lives. The Lansdown estate was established in 1850 by William Guise Brittan, the first man to buy land from the Canterbury Association scheme. The Lansdown-Halswell Run was named after Lansdown Crescent and Lansdown Hill in Bath, the home of William Beckford, author of Vathek, the first Gothic novel written in the English language. Brittan first developed his town sites and home in Fitzgerald Ave before starting on his leasehold land, which reached from Lincoln to Mt Pleasant. It was a huge two-story house, built from the formidable basalt rock of the Halswell Quarry. Brittan bankrupted himself building the house.

The next owner was its most famous: Sir Edward Stafford, three times the New Zealand premier in the 19th century. A well-known landscaper who helped lay out the Auckland Domain, Stafford lived at Lansdown for only five years, but by the time the property was sold after his death, the grounds were referred to as the "Garden of Canterbury".

The spate of losses in the grandparents’ generation in the 1890s was followed by losses among the Callaghan and Birdling parents and siblings in the first decade of the 20th Century. Arthur’s mother Jane Loverage Birdling died in 1900. The Birdlings saw three losses in 1902 with father William in May and brothers Robert and George in August. Two years later, brother Frederick passed. In 1907, Emily lost her father Patrick. This led to her mother Emma moving into Lansdown. Personal losses were about to give way to global losses.

World War I (aka The Great War or the War to End all Wars) broke out in August of 1914 and lasted until November of 1918. It is estimated that 9 million soldiers lost their lives, another 23 million were wounded, and 5 million civilians died from stray fire, disease, and hunger. It was one of the deadliest conflicts in human history.

In response to the Napoleonic Wars a century earlier, the nations of Europe devised a series of non-aggression and mutual support treaties in an attempt to maintain a fragile balance of power that would avoid all-out war. The primary architect of the plan was Klemens von Metternich, a conservative Austro-Hungarian diplomat who was concerned with both France and Russia’s expansionist intentions. The hope was that colonial expansion abroad, especially in Africa, Asia, and the South Pacifica, would redirect expansion away from Central Europe. It worked for quite a while, but nationalist and imperialist sentiments slowly ramped up tensions throughout the region. The unification of Italy in 1866 and of Germany in 1871 added two more strong players to the mix.

The tension had a very personal flavor to it as well. Most of the European monarchs were closely related, being or being married to one of the 42 grandchildren of Queen Victoria. In particular, Kaiser Wilhelm of Germany seems to have had a severe inferiority complex when it came to his cousins George V and Tsar Nicolas II. His personal complex mirrored that of the country’s and was fed by military insecurities that were both person and national.

The first domino among the mutual cooperation pacts was tipped over by the assassination of the Archduke Franz Ferdinand, heir presumptive of the Austro-Hungarian Empire (and one of the few characters involved who was not related to Victoria). Wilhelm was ready and itching for the fight. He put into play the Schlieffen Plan, which called for a fast strike through Belgium to capture Paris before opening a second front against Russia. It might have worked if the Belgians had not put up the fight they did. [For more, read Barbara Tuchman’s The Guns of August. It is excellent.] By Christmas, the German advance had stalled and a stalemate existed across parallel trenches from the Ardenne Forest to the North Sea. By the next year, new fronts were being opened in Greece and the Middle East.

The War immediately became personal for the Birdlings in 1914 when their sons Jack and Gerald and their nephews Reginald, Frank, Percy, Walter, and Ernest all enlisted in the Canterbury Mounted Rifles. Gerald and Reginald went in as troopers and embarked from Lyttleton in October, bound for training in Egypt. Jack, because of his education, was put through officer training and embarked the following August as a 2nd Lieutenant. Reggie was sent to Gallipoli, where he was killed sometime between August 5 and 7, 1915. Gerald and Jack had been promoted during training in Egypt—Gerald to Sergeant and Jackie to 1st Lieutenant. Then they were sent to the Somme River, France.

With a bloody war of attrition going on at Verdun, the British had decided to try and break that stalemate by attacking German-held territory along the River Somme. They first launched a week-long artillery assault. This, they thought, would weaken German lines enough that waves of troops could then march across no-man’s-land to overrun them.

On 1 July 1916, the first wave of eleven British and five French divisions were ordered ‘over the top’. The Germans, however, were still strong (and plans of the offensive had been leaked!), and vast numbers of Allied troops were mown down by machine-gun fire. By the end of the day the British had suffered 60,000 casualties. The British did not give up. Over the following weeks, more troops were sent out and cut down.

The Battle of the Somme was a five-month offensive intended to break the stalemate on the Western Front and end the War quickly. Over 3 million men fought there and over a million died, making it one of the most deadly battles of the War.

On September 15th near the village of Longueval, the New Zealand Division’s turn came. This was to be their first major engagement on the Western Front. Around 6,000 New Zealand soldiers went over the top at 6.20 a.m. By the end of the day, they had achieved their objective and helped take the village of Flers, but 600 of them lay dead. Over the coming days, the New Zealand Division helped capture Morval and Thiepval Ridge. These were small victories, however, and casualties remained horrifically high. Gerald was one of those wounded near Flers, France, on September 16th. He was shipped to London to recuperate before heading back to New Zealand and serving in the Home Guard until 1919.

As a 1st Lieutenant, Jack was at the front of his troops on September 20th, leading the assault that would come to be known as the Battle of Goose Alley. According to a letter to his mother from Lt V.E. McGowan (later published in Jack’s school magazine):

…It was the night of September 20th that Canterbury had to push forward and were getting a sad time. The officers were all killed in this advance…Just as your son was jumping into the German trench, he was shot just below the heart. He got into the trench, gave orders to the men as to what they must do; in fact, he several times said “Bomb them right down the trench, boys.” He was sitting on the first step of the trench. He gradually lost consciousness, and when the stretcher bearers took him out, he was quite unconscious and died just before they reached the field dressing station. He is buried in the soldiers’ cemetery just before going into Flers. On the right side close to the road. There is a little cross with his number and name at his grave.

His name is on the ANZAC Memorial at Caterpillar Valley, Departement de la Somme, Picardie, France.

The Great War ended on November 18, 1918, but life had another blow to land on the Birdlings. In 1919, Emily’s mother contracted a severe illness. She recovered but was suffering from depression. Emily did not think she could continue to provide care and had Emma moved to a private hospital / sanitarium. On November 30, 1920, Emma slipped away from her nurse and threw herself into the nearby Avon River.

The Twenties were a much better decade for the Birdlings than the ‘Teens. Business was booming and the Birdlings were well-off. Arthur had become a successful cattleman like his father. He was a regular attendant at the Addington stock market. His long experience among cattle had earned him a reputation as an authority, and he was called upon to judge the cattle sections at many agricultural and pastoral shows.

Having her own inheritance from her father, Emily began to invest in art. In particular, she purchased three painting by up-and-coming watercolor artist John Haley (1888-1954). Haley was a professional artist from Liverpool who moved with his wife to New Zealand after the war. According to the Auckland Art Gallery website:

The next owner was its most famous: Sir Edward Stafford, three times the New Zealand premier in the 19th century. A well-known landscaper who helped lay out the Auckland Domain, Stafford lived at Lansdown for only five years, but by the time the property was sold after his death, the grounds were referred to as the "Garden of Canterbury".

The spate of losses in the grandparents’ generation in the 1890s was followed by losses among the Callaghan and Birdling parents and siblings in the first decade of the 20th Century. Arthur’s mother Jane Loverage Birdling died in 1900. The Birdlings saw three losses in 1902 with father William in May and brothers Robert and George in August. Two years later, brother Frederick passed. In 1907, Emily lost her father Patrick. This led to her mother Emma moving into Lansdown. Personal losses were about to give way to global losses.

World War I (aka The Great War or the War to End all Wars) broke out in August of 1914 and lasted until November of 1918. It is estimated that 9 million soldiers lost their lives, another 23 million were wounded, and 5 million civilians died from stray fire, disease, and hunger. It was one of the deadliest conflicts in human history.

In response to the Napoleonic Wars a century earlier, the nations of Europe devised a series of non-aggression and mutual support treaties in an attempt to maintain a fragile balance of power that would avoid all-out war. The primary architect of the plan was Klemens von Metternich, a conservative Austro-Hungarian diplomat who was concerned with both France and Russia’s expansionist intentions. The hope was that colonial expansion abroad, especially in Africa, Asia, and the South Pacifica, would redirect expansion away from Central Europe. It worked for quite a while, but nationalist and imperialist sentiments slowly ramped up tensions throughout the region. The unification of Italy in 1866 and of Germany in 1871 added two more strong players to the mix.

The tension had a very personal flavor to it as well. Most of the European monarchs were closely related, being or being married to one of the 42 grandchildren of Queen Victoria. In particular, Kaiser Wilhelm of Germany seems to have had a severe inferiority complex when it came to his cousins George V and Tsar Nicolas II. His personal complex mirrored that of the country’s and was fed by military insecurities that were both person and national.

The first domino among the mutual cooperation pacts was tipped over by the assassination of the Archduke Franz Ferdinand, heir presumptive of the Austro-Hungarian Empire (and one of the few characters involved who was not related to Victoria). Wilhelm was ready and itching for the fight. He put into play the Schlieffen Plan, which called for a fast strike through Belgium to capture Paris before opening a second front against Russia. It might have worked if the Belgians had not put up the fight they did. [For more, read Barbara Tuchman’s The Guns of August. It is excellent.] By Christmas, the German advance had stalled and a stalemate existed across parallel trenches from the Ardenne Forest to the North Sea. By the next year, new fronts were being opened in Greece and the Middle East.

The War immediately became personal for the Birdlings in 1914 when their sons Jack and Gerald and their nephews Reginald, Frank, Percy, Walter, and Ernest all enlisted in the Canterbury Mounted Rifles. Gerald and Reginald went in as troopers and embarked from Lyttleton in October, bound for training in Egypt. Jack, because of his education, was put through officer training and embarked the following August as a 2nd Lieutenant. Reggie was sent to Gallipoli, where he was killed sometime between August 5 and 7, 1915. Gerald and Jack had been promoted during training in Egypt—Gerald to Sergeant and Jackie to 1st Lieutenant. Then they were sent to the Somme River, France.

With a bloody war of attrition going on at Verdun, the British had decided to try and break that stalemate by attacking German-held territory along the River Somme. They first launched a week-long artillery assault. This, they thought, would weaken German lines enough that waves of troops could then march across no-man’s-land to overrun them.

On 1 July 1916, the first wave of eleven British and five French divisions were ordered ‘over the top’. The Germans, however, were still strong (and plans of the offensive had been leaked!), and vast numbers of Allied troops were mown down by machine-gun fire. By the end of the day the British had suffered 60,000 casualties. The British did not give up. Over the following weeks, more troops were sent out and cut down.

The Battle of the Somme was a five-month offensive intended to break the stalemate on the Western Front and end the War quickly. Over 3 million men fought there and over a million died, making it one of the most deadly battles of the War.

On September 15th near the village of Longueval, the New Zealand Division’s turn came. This was to be their first major engagement on the Western Front. Around 6,000 New Zealand soldiers went over the top at 6.20 a.m. By the end of the day, they had achieved their objective and helped take the village of Flers, but 600 of them lay dead. Over the coming days, the New Zealand Division helped capture Morval and Thiepval Ridge. These were small victories, however, and casualties remained horrifically high. Gerald was one of those wounded near Flers, France, on September 16th. He was shipped to London to recuperate before heading back to New Zealand and serving in the Home Guard until 1919.

As a 1st Lieutenant, Jack was at the front of his troops on September 20th, leading the assault that would come to be known as the Battle of Goose Alley. According to a letter to his mother from Lt V.E. McGowan (later published in Jack’s school magazine):

…It was the night of September 20th that Canterbury had to push forward and were getting a sad time. The officers were all killed in this advance…Just as your son was jumping into the German trench, he was shot just below the heart. He got into the trench, gave orders to the men as to what they must do; in fact, he several times said “Bomb them right down the trench, boys.” He was sitting on the first step of the trench. He gradually lost consciousness, and when the stretcher bearers took him out, he was quite unconscious and died just before they reached the field dressing station. He is buried in the soldiers’ cemetery just before going into Flers. On the right side close to the road. There is a little cross with his number and name at his grave.

His name is on the ANZAC Memorial at Caterpillar Valley, Departement de la Somme, Picardie, France.

The Great War ended on November 18, 1918, but life had another blow to land on the Birdlings. In 1919, Emily’s mother contracted a severe illness. She recovered but was suffering from depression. Emily did not think she could continue to provide care and had Emma moved to a private hospital / sanitarium. On November 30, 1920, Emma slipped away from her nurse and threw herself into the nearby Avon River.

The Twenties were a much better decade for the Birdlings than the ‘Teens. Business was booming and the Birdlings were well-off. Arthur had become a successful cattleman like his father. He was a regular attendant at the Addington stock market. His long experience among cattle had earned him a reputation as an authority, and he was called upon to judge the cattle sections at many agricultural and pastoral shows.

Having her own inheritance from her father, Emily began to invest in art. In particular, she purchased three painting by up-and-coming watercolor artist John Haley (1888-1954). Haley was a professional artist from Liverpool who moved with his wife to New Zealand after the war. According to the Auckland Art Gallery website:

"He exhibited with dealer galleries in Auckland and was an exhibiting and working member of the Auckland Society of Arts between 1921 and 1927. Haley is understood to have enjoyed driving around the environs of Auckland in his baby Austin 7, stopping to paint with a watercolour block resting on the steering wheel. He was also known to row around the local coastline sourcing subjects for his paintings.

He later taught art at Takapuna Primary School.

The Birdlings were well-enough off to establish a scholarship in Jack’s a name at their son’s school. According to The Press (1925):

The Canterbury College Board of Governors yesterday accepted a donation of £2OO presented by Mr. and Mrs. Arthur Birdling, of Halswell, for the establishment of a Memorial Prize at the Boys’ High School, in “History of the British Empire, with special reference to foreign relations.” The chairman of the High Schools and Hostels Committee, Mr C. T. Aschman, stated that the gift was a memorial to Jack Birdling, a son of the donors, an Old Boy of the School, who had been killed in France, history being his favorite subject.

Gerald and Eileen had both married in 1920. The birth of Gerald’s daughter Janet Catherine Birdling on September 13, 1921, made Emily and Arthur grandparents. They would have 21 grandchildren over the next 30 years. Emily often traveled to Timaru where her daughter had relocated. Her grandson James Birdling Stewart had very fond memories of “Granny Birdling.”

Bust follows boom follows bust follows boom. The 1929 Stock Market Crash did not immediately affect New Zealand as much as it did elsewhere around the world. But from 1930 export prices began to plummet, falling 45% by 1933. This was devastating to a country dependent on agricultural exports. By the end of 1930, businesses and manufacturers were feeling the effects.

According to The Depression of the Thirties (https://teara.govt.nz/en/1966/history-economic/page-7):

For New Zealand, as for most of the world outside Russia, the great depression of the early 1930s was the most shattering economic experience ever recorded. Exports fell by 45 per cent in two years, national income by 40 per cent in three. The balance of payments was further weakened by the burden of interest on the overseas debt. At the worst point of the depression, the number of unemployed may have exceeded 70,000 – ambiguities of definition make a precise estimate difficult. The sharpest price fall was that of wool, which declined by 60 per cent from 1929 to 1932; meat fell a good deal less. The dairy price index continued to fall until 1934; dairy farmers tried to make ends meet by increasing production during the depression and in doing so forced the export prices of butter and cheese still lower: butter exported rose from 1,654,000 cwt in 1929 to 2,635,000 in 1933; cheese exports also rose, though much less rapidly.

The depression has rightly been described as a traumatic experience; for the second time at least since the founding of the colony, new New Zealanders found themselves disillusioned by the appearance in their adopted country of conditions they thought they had escaped from. As in the late 1880s, there was some net emigration in the early 1930s; as on the earlier occasion, again, most of the would-be emigrants could not afford the fare to leave. Perhaps as well; for this time, at least, they were not justified in thinking they had made the worst of the bargain. Bad as were conditions in New Zealand, they were perhaps less demoralising than those in Jarrow or on Clydeside, and percentages of the labour force unemployed were a good deal higher in many industrial countries, and in Australia.

The depression was, in fact, aggravated by New Zealand's extreme unpreparedness to meet it. Despite New Zealand's early reputation as a “social laboratory”, her social services had in fact fallen behind those of many other countries in the post-1918 years, and the country entered the depression without even the modest provision for unemployment relief by which the British industrial worker was protected. The policy of the Coalition Government formed in September 1931 was on the whole unenterprising and, perhaps inevitably, unenlightened in the Keynesian sense of the word. As elsewhere, the chief concern was to balance the budget, though overseas borrowing continued until 1933. Some of the public works which formed the main relief measure were, however, useful. Especially notable were the schemes for the development of Maori land (conceived before the depression but speeded up essentially as relief work), which accorded well with the marked resurgence of the Maori people since the late nineteenth century, and the planting of exotic trees in the centre of the North Island, which was to lead to a thriving development of forest products.

Most of the positive measures were conceived to help the farm community whose net income, according to one expert calculation, was zero in 1930–31 and a negative quantity in 1931–32. From 1931 the Government adopted a scheme first tried privately on the initiative of the Canterbury Chamber of Commerce, whereby mortgage commitments were scaled down by agreement between the farmer and his mortgagee. In 1933 the New Zealand pound, which had already slipped to a discount of about 10 per cent, was devalued, £125 equalling 100 sterling at the new rate of exchange. The year before, the Imperial Conference at Ottawa had set up the structure of Imperial preference which has since remained the basis of New Zealand's trade with the United Kingdom, though the importance of the concessions, particularly as regards New Zealand exports to Britain, has been somewhat eroded with the passage of time. However, a British proposal to impose quota restrictions on butter imports and an unsuccessful experiment in placing such quotas on meat, shocked New Zealand opinion into its first acquaintance with an idea which has since become only too familiar – that the British market is not a bottomless pit into which anything New Zealand can produce may be profitably poured. Belief that Coates, Minister of Finance in the Coalition Government, had aided and abetted the British government's plan for a butter quota, was one reason for the loss of confidence in the Administration on the part of the dairy farmers, and their readiness to vote for a Labour Party which promised a guaranteed price for their products.

It is hard to measure the effects of the Great Depression on the Birdling family. The blows to investments and agricultural export struck at the heart of the Birdling’s wealth. On the other hand, Arthur was a tough, smart old farmer who was not scared of hard work, even as he got older. Already in their mid- to late- sixties, he and Emily would have been more conservative in their investments. Her last will shows that Emily had a significant estate of her own to leave her children and that she used it during the Depression to help at least one of them to make ends meet. The situation was probably harder on their children, who were in the middle of their earning years and had little children to raise and provide for.

As often happens, war followed Depression and was a major cause to financial recovery. World War II broke out in Europe in 1939. Conscription was instituted throughout the British Empire in June of 1940. Difficulties in filling the Second and Third Echelons for overseas service in 1939–1940, the Allied disasters of May 1940, and public demand led to its introduction. Four members of the cabinet, including Prime Minister Peter Fraser, had been imprisoned for anti-conscription activities in World War I. The Labour Party was traditionally opposed to it. Some members still demanded conscription of wealth before men. From January 1942, workers could be manpowered—that is, directed to essential industries—instead of drafted into the Army. In total, around 140,000 New Zealand personnel served overseas for the Allied war effort, and an additional 100,000 men were armed for Home Guard duty. At its peak in July 1942, New Zealand had 154,549 men and women under arms (excluding the Home Guard) and, by the War's end, a total of 194,000 men and 10,000 women had served in the armed forces at home and abroad. To alleviate manpower shortages in the agricultural sector, the New Zealand Women's Land Army was created in 1940. A total of 2,711 women served on farms throughout New Zealand during the war.

Japanese battleships and economic needs elsewhere in the Empire limited imports severely. In their homes, New Zealanders also learned to do without – or at least with less. From early in 1942, the regular cuppa had to be reconsidered, as first sugar and then tea were rationed. Rubber was also scarce after Malaya and the Dutch East Indies fell to the Japanese, at the beginning of 1942. At that point, 90% of the world's supply of raw rubber was in enemy hands. Tires were reserved for priority use, and private motorists were again the last in line. The rubber shortage affected other daily necessities as well. To get a pair of gumboots, dairy farmers had to prove they owned at least 12 cows.

In New Zealand as elsewhere in the world, industry switched from civilian needs to making war materials on a much larger scale. New Zealand and Australia supplied the bulk of foodstuffs to American forces in the South Pacific, as Reverse Lend-Lease. With earlier commitments to supply food to Britain, this led to both Britain and America complaining about food going to the other ally (and Britain commenting on the much more generous ration allocations for American soldiers).

In 1940, the Birdlings celebrated their 50th Wedding Anniversary. With the War on, it does not seem to have made the papers. Under the circumstances, any celebration would have been understated compared to, say, their 25th Anniversary in 1925.

Emily Callaghan Birding died on August 4, 1943, at her daughter’s home at Clover Hill, Totara Valley, Timaru, New Zealand. She was 75 years old. The cause of death was age-related kidney failure which resulted in a 4 our coma. She was buried at the new Ruru Lawn Cemetery in Bromley, outside of Christchurch City.

He later taught art at Takapuna Primary School.

The Birdlings were well-enough off to establish a scholarship in Jack’s a name at their son’s school. According to The Press (1925):

The Canterbury College Board of Governors yesterday accepted a donation of £2OO presented by Mr. and Mrs. Arthur Birdling, of Halswell, for the establishment of a Memorial Prize at the Boys’ High School, in “History of the British Empire, with special reference to foreign relations.” The chairman of the High Schools and Hostels Committee, Mr C. T. Aschman, stated that the gift was a memorial to Jack Birdling, a son of the donors, an Old Boy of the School, who had been killed in France, history being his favorite subject.

Gerald and Eileen had both married in 1920. The birth of Gerald’s daughter Janet Catherine Birdling on September 13, 1921, made Emily and Arthur grandparents. They would have 21 grandchildren over the next 30 years. Emily often traveled to Timaru where her daughter had relocated. Her grandson James Birdling Stewart had very fond memories of “Granny Birdling.”

Bust follows boom follows bust follows boom. The 1929 Stock Market Crash did not immediately affect New Zealand as much as it did elsewhere around the world. But from 1930 export prices began to plummet, falling 45% by 1933. This was devastating to a country dependent on agricultural exports. By the end of 1930, businesses and manufacturers were feeling the effects.

According to The Depression of the Thirties (https://teara.govt.nz/en/1966/history-economic/page-7):

For New Zealand, as for most of the world outside Russia, the great depression of the early 1930s was the most shattering economic experience ever recorded. Exports fell by 45 per cent in two years, national income by 40 per cent in three. The balance of payments was further weakened by the burden of interest on the overseas debt. At the worst point of the depression, the number of unemployed may have exceeded 70,000 – ambiguities of definition make a precise estimate difficult. The sharpest price fall was that of wool, which declined by 60 per cent from 1929 to 1932; meat fell a good deal less. The dairy price index continued to fall until 1934; dairy farmers tried to make ends meet by increasing production during the depression and in doing so forced the export prices of butter and cheese still lower: butter exported rose from 1,654,000 cwt in 1929 to 2,635,000 in 1933; cheese exports also rose, though much less rapidly.

The depression has rightly been described as a traumatic experience; for the second time at least since the founding of the colony, new New Zealanders found themselves disillusioned by the appearance in their adopted country of conditions they thought they had escaped from. As in the late 1880s, there was some net emigration in the early 1930s; as on the earlier occasion, again, most of the would-be emigrants could not afford the fare to leave. Perhaps as well; for this time, at least, they were not justified in thinking they had made the worst of the bargain. Bad as were conditions in New Zealand, they were perhaps less demoralising than those in Jarrow or on Clydeside, and percentages of the labour force unemployed were a good deal higher in many industrial countries, and in Australia.

The depression was, in fact, aggravated by New Zealand's extreme unpreparedness to meet it. Despite New Zealand's early reputation as a “social laboratory”, her social services had in fact fallen behind those of many other countries in the post-1918 years, and the country entered the depression without even the modest provision for unemployment relief by which the British industrial worker was protected. The policy of the Coalition Government formed in September 1931 was on the whole unenterprising and, perhaps inevitably, unenlightened in the Keynesian sense of the word. As elsewhere, the chief concern was to balance the budget, though overseas borrowing continued until 1933. Some of the public works which formed the main relief measure were, however, useful. Especially notable were the schemes for the development of Maori land (conceived before the depression but speeded up essentially as relief work), which accorded well with the marked resurgence of the Maori people since the late nineteenth century, and the planting of exotic trees in the centre of the North Island, which was to lead to a thriving development of forest products.

Most of the positive measures were conceived to help the farm community whose net income, according to one expert calculation, was zero in 1930–31 and a negative quantity in 1931–32. From 1931 the Government adopted a scheme first tried privately on the initiative of the Canterbury Chamber of Commerce, whereby mortgage commitments were scaled down by agreement between the farmer and his mortgagee. In 1933 the New Zealand pound, which had already slipped to a discount of about 10 per cent, was devalued, £125 equalling 100 sterling at the new rate of exchange. The year before, the Imperial Conference at Ottawa had set up the structure of Imperial preference which has since remained the basis of New Zealand's trade with the United Kingdom, though the importance of the concessions, particularly as regards New Zealand exports to Britain, has been somewhat eroded with the passage of time. However, a British proposal to impose quota restrictions on butter imports and an unsuccessful experiment in placing such quotas on meat, shocked New Zealand opinion into its first acquaintance with an idea which has since become only too familiar – that the British market is not a bottomless pit into which anything New Zealand can produce may be profitably poured. Belief that Coates, Minister of Finance in the Coalition Government, had aided and abetted the British government's plan for a butter quota, was one reason for the loss of confidence in the Administration on the part of the dairy farmers, and their readiness to vote for a Labour Party which promised a guaranteed price for their products.

It is hard to measure the effects of the Great Depression on the Birdling family. The blows to investments and agricultural export struck at the heart of the Birdling’s wealth. On the other hand, Arthur was a tough, smart old farmer who was not scared of hard work, even as he got older. Already in their mid- to late- sixties, he and Emily would have been more conservative in their investments. Her last will shows that Emily had a significant estate of her own to leave her children and that she used it during the Depression to help at least one of them to make ends meet. The situation was probably harder on their children, who were in the middle of their earning years and had little children to raise and provide for.

As often happens, war followed Depression and was a major cause to financial recovery. World War II broke out in Europe in 1939. Conscription was instituted throughout the British Empire in June of 1940. Difficulties in filling the Second and Third Echelons for overseas service in 1939–1940, the Allied disasters of May 1940, and public demand led to its introduction. Four members of the cabinet, including Prime Minister Peter Fraser, had been imprisoned for anti-conscription activities in World War I. The Labour Party was traditionally opposed to it. Some members still demanded conscription of wealth before men. From January 1942, workers could be manpowered—that is, directed to essential industries—instead of drafted into the Army. In total, around 140,000 New Zealand personnel served overseas for the Allied war effort, and an additional 100,000 men were armed for Home Guard duty. At its peak in July 1942, New Zealand had 154,549 men and women under arms (excluding the Home Guard) and, by the War's end, a total of 194,000 men and 10,000 women had served in the armed forces at home and abroad. To alleviate manpower shortages in the agricultural sector, the New Zealand Women's Land Army was created in 1940. A total of 2,711 women served on farms throughout New Zealand during the war.

Japanese battleships and economic needs elsewhere in the Empire limited imports severely. In their homes, New Zealanders also learned to do without – or at least with less. From early in 1942, the regular cuppa had to be reconsidered, as first sugar and then tea were rationed. Rubber was also scarce after Malaya and the Dutch East Indies fell to the Japanese, at the beginning of 1942. At that point, 90% of the world's supply of raw rubber was in enemy hands. Tires were reserved for priority use, and private motorists were again the last in line. The rubber shortage affected other daily necessities as well. To get a pair of gumboots, dairy farmers had to prove they owned at least 12 cows.

In New Zealand as elsewhere in the world, industry switched from civilian needs to making war materials on a much larger scale. New Zealand and Australia supplied the bulk of foodstuffs to American forces in the South Pacific, as Reverse Lend-Lease. With earlier commitments to supply food to Britain, this led to both Britain and America complaining about food going to the other ally (and Britain commenting on the much more generous ration allocations for American soldiers).

In 1940, the Birdlings celebrated their 50th Wedding Anniversary. With the War on, it does not seem to have made the papers. Under the circumstances, any celebration would have been understated compared to, say, their 25th Anniversary in 1925.

Emily Callaghan Birding died on August 4, 1943, at her daughter’s home at Clover Hill, Totara Valley, Timaru, New Zealand. She was 75 years old. The cause of death was age-related kidney failure which resulted in a 4 our coma. She was buried at the new Ruru Lawn Cemetery in Bromley, outside of Christchurch City.

On January 19, 1944, a fire broke out at Lansdown, burning the house to the ground. According to The Press (20 Jan 1944):

Fire completely destroyed the home of Mr A. Birdling, at Lansdown, Halswell, yesterday afternoon. The house was a large two-story building, about 60 or 70 years old, and it was fully furnished when the fire broke out. Little was salvaged from the fire. The alarm was given about 3:30 o’clock, but the property was well beyond the Christchurch Fire Brigade’s district, and it was not long before it looked a hopeless task to save the house. Residents from adjoining properties hurried in cars to assist, but it was impossible to do anything to check the flames. Assistance was also given by men from Wigram, and efforts were concentrated on averting a grass fire on land surrounding the house. As fires broke out in the grass, they were stamped out, and damage to the fine grounds of the property was avoided. By about half-past five the house was burnt to the ground.

Much of Emily’s art collection, including most of her own works, was destroyed. Family photos, needlepoint, keepsakes, all gone. The house was rebuilt and was later sold to Haydn Rawstron who grew up nearby. It is now Lansdown Homestead and Park, a venue for weddings and small concerts and picnics on the homestead lawn beside the banks of the Halswell River.

Arthur survived Emily by 19 years. As a link to the distant past, his story was in the newspapers in 1952 and 1959 for his 89th and 96th birthdays respectively. The Press (1952):

Hard work, which he considers hurts no man, plenty of sleep, the drinking of plenty of water, and moderation in smoking are some of the things that Mr. Birdling thinks contribute to long life. He is critical of the present age and generation. In his view, people are no longer as sociable as formerly and are now “out for their own ends.” He is also perturbed at the tendency to seek more money for less work.

In spite of his age, Mr. Birdling is still wonderfully agile and, until last year, he attended his own vegetable garden. Every morning, Miss B. Noble, who has looked after Mr. Birdling since his wife died nine years ago, reads his newspaper to him.

Arthur died at Halswell on October 12, 1962. He was six months shy of his 100th birthday. He was buried at St. Mary’s Anglican Church Cemetery, Halswell. Why he was not buried with Emily is unknown. Possibly, it was a religious matter.

Fire completely destroyed the home of Mr A. Birdling, at Lansdown, Halswell, yesterday afternoon. The house was a large two-story building, about 60 or 70 years old, and it was fully furnished when the fire broke out. Little was salvaged from the fire. The alarm was given about 3:30 o’clock, but the property was well beyond the Christchurch Fire Brigade’s district, and it was not long before it looked a hopeless task to save the house. Residents from adjoining properties hurried in cars to assist, but it was impossible to do anything to check the flames. Assistance was also given by men from Wigram, and efforts were concentrated on averting a grass fire on land surrounding the house. As fires broke out in the grass, they were stamped out, and damage to the fine grounds of the property was avoided. By about half-past five the house was burnt to the ground.

Much of Emily’s art collection, including most of her own works, was destroyed. Family photos, needlepoint, keepsakes, all gone. The house was rebuilt and was later sold to Haydn Rawstron who grew up nearby. It is now Lansdown Homestead and Park, a venue for weddings and small concerts and picnics on the homestead lawn beside the banks of the Halswell River.

Arthur survived Emily by 19 years. As a link to the distant past, his story was in the newspapers in 1952 and 1959 for his 89th and 96th birthdays respectively. The Press (1952):

Hard work, which he considers hurts no man, plenty of sleep, the drinking of plenty of water, and moderation in smoking are some of the things that Mr. Birdling thinks contribute to long life. He is critical of the present age and generation. In his view, people are no longer as sociable as formerly and are now “out for their own ends.” He is also perturbed at the tendency to seek more money for less work.

In spite of his age, Mr. Birdling is still wonderfully agile and, until last year, he attended his own vegetable garden. Every morning, Miss B. Noble, who has looked after Mr. Birdling since his wife died nine years ago, reads his newspaper to him.

Arthur died at Halswell on October 12, 1962. He was six months shy of his 100th birthday. He was buried at St. Mary’s Anglican Church Cemetery, Halswell. Why he was not buried with Emily is unknown. Possibly, it was a religious matter.

Arthur John and Emily were a well-matched pair. Both were children of immigrants who had made it big through hard work and determination. They were married for 53 years, had 4 children and 21 grandchildren together, and suffered the highs and lows of one of the most tumultuous time periods in human history. Though they had privileged childhoods, they learned the lessons of hard work and self-reliance from their parents and passed those lessons on to their children. They are ancestors of whom anyone can be proud, and they set a high bar for us to achieve. Hopefully when they are looking down on us, they are proud of what they see.