James Callaghan

Birth: 29 Aug 1844, Kilbreedy Minor, Mount Blakeny, Limerick, Ireland

Death: 26 Jun 1939, Glen Osmond, South Australia

Burial: Adelaide, Adelaide City, South Australia

Never married, no children

James Callaghan was born on August 29, 1844, in the midst of the family’s eviction proceedings and just before the Great Famine struck. Unlike his siblings, he would never know what it was like to live on the Fitzgerald Estate nor have a connection to the land his father’s family had worked for a century. He would only remember his mother’s property where they rented a house and served as farm laborers to his uncle James Carroll. He was likely named for that uncle.

James was baptized at Effin Church on August 31, 1844. His godparents were William Callaghan (likely his uncle) and Margaret Keefe, possibly the wife of the neighbor in Mountblakeney who temporarily sublet a cottage to the Callaghans after their eviction and before they moved to Effin.

Death: 26 Jun 1939, Glen Osmond, South Australia

Burial: Adelaide, Adelaide City, South Australia

Never married, no children

James Callaghan was born on August 29, 1844, in the midst of the family’s eviction proceedings and just before the Great Famine struck. Unlike his siblings, he would never know what it was like to live on the Fitzgerald Estate nor have a connection to the land his father’s family had worked for a century. He would only remember his mother’s property where they rented a house and served as farm laborers to his uncle James Carroll. He was likely named for that uncle.

James was baptized at Effin Church on August 31, 1844. His godparents were William Callaghan (likely his uncle) and Margaret Keefe, possibly the wife of the neighbor in Mountblakeney who temporarily sublet a cottage to the Callaghans after their eviction and before they moved to Effin.

The house where James grew up was not much. According to the House Book for Coshma Parish, Limerick, his mother Nora had been willed the right to lease one acre of land and the old house upon the death of her father Michael Carroll. The rest of the land around the house was leased to her brother James. Valued at £1 s0 d0, the house was most likely what was known as a bothán (a fourth-class house which was a mere hovel made of mud and sticks with a thatched roof), and a poor, dilapidated one at that. Similar to the house pictured here from Bakers Flat, South Australia, the family of ten would have been squeezed into one or two rooms of about 200 square feet total. Likely the space would have been shared with farm animals at night for the warmth. Living conditions would have been harsh by modern standards, with limited access to amenities like water and privies.

As seen throughout the family’s eviction process, there was a clear social hierarchy in Ireland of the time, with landlords and the British ruling class at the top, followed by farmers and laborers. The move to the Carroll land would have dropped the Callaghans to the bottom of the ladder. Not only were they now laborers instead of tenant farmers, they were beholden to the good will of the Carrolls. Added to that would have been the shame of having lost the century-long tenancy of the Callaghans on the Fitzgerald Estate. But at least the family held together—for the moment.

James would have been raised around many children. Not only did he have seven siblings, there were at least a dozen Carroll cousins nearby and many more in the parish. There was little or no formal education available in Effin, and what was available would have been too expensive for the Callaghans. Their first exposure to formal education would occur aboard ship on their way to Australia. That would make a significant impact on the brothers (the girls did not receive instruction) and William, Michael, and Patrick, in particular, would become involved in local schoolboards when they became successful farmers and businessmen later in life.

The vast majority of the population was Catholic, and religious practices played a significant role in daily life. James and his siblings would demonstrate significant devotion to the Church throughout the rest of their lives.

Farming was a primary occupation for most families in Effin, and small farms were common. Tenants relied on subsistence farming to support their families. Children were expected to contribute to the family's economic well-being from a young age. The Great Famine had devastating effects on the population, leading to widespread hunger, disease, and death. Many families were torn apart, and a significant number of people emigrated in search of a better life. One million people died—mostly in the West—and another million emigrated, slashing the population by nearly 25%. The dates of the Great Famine are usually listed as 1845 – 1849, though some historians stop at 1847 and others view the disaster as continuing to 1852. But the Blight on the potato crop returned repeatedly through the 1850s.

James was only ten when he started losing family members. The Callaghans held out as long as they could, but, in 1854, James’ eldest brother William emigrated to American to find work in Illinois where they had Carroll relatives. In 1855, their sister Mary traveled to South Australia for work. On board the ship South Sea were Carroll cousins as well. Shortly after that, James’ mother Nora died, and his father decided to try his luck in Australia as well.

In July of 1858, fourteen-year-old James and his family boarded the ship Bee, likely in Cobh Harbor, Cork, and set sail for Adelaide, South Australia. Passage was paid by the British government to induce laborers to come to the growing colony. John had signed himself and his sons up for a two-year stint as basically indentured servants.

One advantage to the trip was free education. Patrick, John, and James are listed on the Incoming and Outgoing Passenger Lists as having attended school aboard the Bee. It is noted that none of them had education in reading, writing, nor arithmetic at the start of the journey. After 57 days of schooling under Schoolmaster of the Ship John A. Boyd (himself listed as a General Emigrant), they had progressed through the 3rd book of reading instruction. James was noted as being “most attentive.” James, being younger than his brothers, was still writing “large,” but his brothers had both progressed to “small” writing. They achieved different levels mathematically, but there is no legend explaining the designations of C.M, C.S., and C.A., respectively. William and Michael attended the Men’s school. They progressed from S.A. to S.D., indicating they came aboard with some education in the three R’s.

Arriving in Adelaide on October 9, 1858, the family immediately moved in with their eldest sister, Mary, who had married John Burns in 1857 and was due to give birth to the first member of the next generation within the month. They lived in a house in Hectorville, a mostly Irish town on the northeast outskirts of Adelaide.

James lived for 81 years in Australia but little is known about his personal life. After his two-year service was done in 1860, James moved to Melbourne where his brother Michael had moved and married. We know that, while there, James joined the St Francis Xavier Branch of the Hibernian Australian Catholic Benefit Society (H.A.C.B.S.), probably when it was formed.

As seen throughout the family’s eviction process, there was a clear social hierarchy in Ireland of the time, with landlords and the British ruling class at the top, followed by farmers and laborers. The move to the Carroll land would have dropped the Callaghans to the bottom of the ladder. Not only were they now laborers instead of tenant farmers, they were beholden to the good will of the Carrolls. Added to that would have been the shame of having lost the century-long tenancy of the Callaghans on the Fitzgerald Estate. But at least the family held together—for the moment.

James would have been raised around many children. Not only did he have seven siblings, there were at least a dozen Carroll cousins nearby and many more in the parish. There was little or no formal education available in Effin, and what was available would have been too expensive for the Callaghans. Their first exposure to formal education would occur aboard ship on their way to Australia. That would make a significant impact on the brothers (the girls did not receive instruction) and William, Michael, and Patrick, in particular, would become involved in local schoolboards when they became successful farmers and businessmen later in life.

The vast majority of the population was Catholic, and religious practices played a significant role in daily life. James and his siblings would demonstrate significant devotion to the Church throughout the rest of their lives.

Farming was a primary occupation for most families in Effin, and small farms were common. Tenants relied on subsistence farming to support their families. Children were expected to contribute to the family's economic well-being from a young age. The Great Famine had devastating effects on the population, leading to widespread hunger, disease, and death. Many families were torn apart, and a significant number of people emigrated in search of a better life. One million people died—mostly in the West—and another million emigrated, slashing the population by nearly 25%. The dates of the Great Famine are usually listed as 1845 – 1849, though some historians stop at 1847 and others view the disaster as continuing to 1852. But the Blight on the potato crop returned repeatedly through the 1850s.

James was only ten when he started losing family members. The Callaghans held out as long as they could, but, in 1854, James’ eldest brother William emigrated to American to find work in Illinois where they had Carroll relatives. In 1855, their sister Mary traveled to South Australia for work. On board the ship South Sea were Carroll cousins as well. Shortly after that, James’ mother Nora died, and his father decided to try his luck in Australia as well.

In July of 1858, fourteen-year-old James and his family boarded the ship Bee, likely in Cobh Harbor, Cork, and set sail for Adelaide, South Australia. Passage was paid by the British government to induce laborers to come to the growing colony. John had signed himself and his sons up for a two-year stint as basically indentured servants.

One advantage to the trip was free education. Patrick, John, and James are listed on the Incoming and Outgoing Passenger Lists as having attended school aboard the Bee. It is noted that none of them had education in reading, writing, nor arithmetic at the start of the journey. After 57 days of schooling under Schoolmaster of the Ship John A. Boyd (himself listed as a General Emigrant), they had progressed through the 3rd book of reading instruction. James was noted as being “most attentive.” James, being younger than his brothers, was still writing “large,” but his brothers had both progressed to “small” writing. They achieved different levels mathematically, but there is no legend explaining the designations of C.M, C.S., and C.A., respectively. William and Michael attended the Men’s school. They progressed from S.A. to S.D., indicating they came aboard with some education in the three R’s.

Arriving in Adelaide on October 9, 1858, the family immediately moved in with their eldest sister, Mary, who had married John Burns in 1857 and was due to give birth to the first member of the next generation within the month. They lived in a house in Hectorville, a mostly Irish town on the northeast outskirts of Adelaide.

James lived for 81 years in Australia but little is known about his personal life. After his two-year service was done in 1860, James moved to Melbourne where his brother Michael had moved and married. We know that, while there, James joined the St Francis Xavier Branch of the Hibernian Australian Catholic Benefit Society (H.A.C.B.S.), probably when it was formed.

The Hibernian Australian Catholic Benefit Society (HACBS) was a church-based support network. It was founded in 1868 by a group of Irish immigrants, including Mark Young.

In 1857, Young arrived in the colony of Victoria from Ireland. He moved to Ballarat, where he worked in a variety of occupations, including keeping a store with his brother. In 1861, he joined a gold rush to Otago, New Zealand, returning to Ballarat in 1862. (James’ brother Patrick had also gone to Otego, but he settled on the Banks Peninsula for the rest of his life instead of returning to Australia.) Young ran the White Hart Hotel in Sturt Street and became very active in local affairs. He assisted other Irishmen in the foundation of the Ballarat Hibernian Benefit Society and later worked to achieve the amalgamation of that society with the Australian Catholic Benefit Society to form the Hibernian Australian Catholic Benefit Society. He was elected as its first president. The Society supported St Patrick's Day parades. In 1953, sixty of its branches marched in the Melbourne parade.

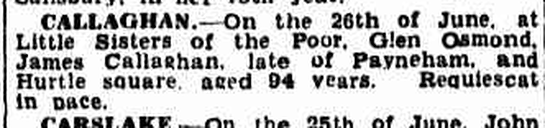

According to his obituary, James moved back to Adelaide in 1887 and transferred his H.A.C.B.S. membership to Cathedral Branch, Adelaide. It is unknown where he lived or worked there. In 1924, he is mentioned in his brother William’s will as living in Salisbury, South Australia. Later, he lived in Hurtle Square, North Adelaide, and Payneham, near Hectorville. As far as is known, James never married nor had any children.

In 1857, Young arrived in the colony of Victoria from Ireland. He moved to Ballarat, where he worked in a variety of occupations, including keeping a store with his brother. In 1861, he joined a gold rush to Otago, New Zealand, returning to Ballarat in 1862. (James’ brother Patrick had also gone to Otego, but he settled on the Banks Peninsula for the rest of his life instead of returning to Australia.) Young ran the White Hart Hotel in Sturt Street and became very active in local affairs. He assisted other Irishmen in the foundation of the Ballarat Hibernian Benefit Society and later worked to achieve the amalgamation of that society with the Australian Catholic Benefit Society to form the Hibernian Australian Catholic Benefit Society. He was elected as its first president. The Society supported St Patrick's Day parades. In 1953, sixty of its branches marched in the Melbourne parade.

According to his obituary, James moved back to Adelaide in 1887 and transferred his H.A.C.B.S. membership to Cathedral Branch, Adelaide. It is unknown where he lived or worked there. In 1924, he is mentioned in his brother William’s will as living in Salisbury, South Australia. Later, he lived in Hurtle Square, North Adelaide, and Payneham, near Hectorville. As far as is known, James never married nor had any children.

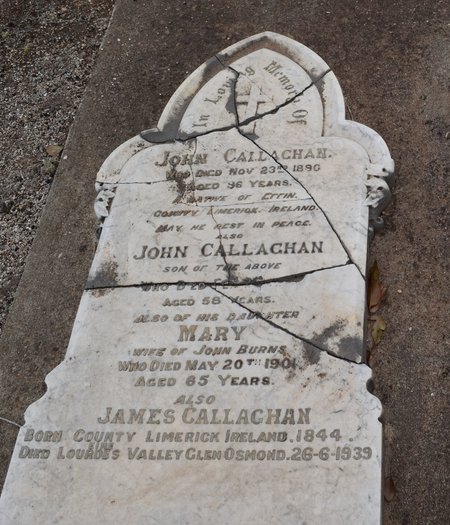

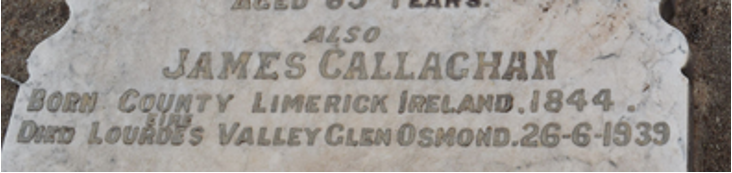

James Callaghan died of old age on June 26, 1939, at the hospital of the Little Sisters of the Poor, Glen Osmond, South Australia. He was 94 years old. He was buried with his father, his brother John, and his sister Mary in West Terrace Cemetery, Adelaide.

It is a shame that such a long life has left so few echoes down the years. As a member of the H.A.C.B.S. for 70 years, he must have touched many people’s lives. But how, we may never know.