Michael A Callaghan and Johanna McCarthy

Birth: 10 Apr 1838, Effin, Co Limerick, Ireland

Death: 9 Aug 1920, Rio Vista, CA

Burial: St. Joseph's Cemetery, Rio Vista

Father: John Callaghan

Mother: Hanora Carroll

Spouse: Johanna McCarthy

Birth: 29 Sep 1833, Co Limerick, Ireland

Death: 9 Apr 1909, Rio Vista, CA

Father: James McCarthy

Mother: Julia Boland

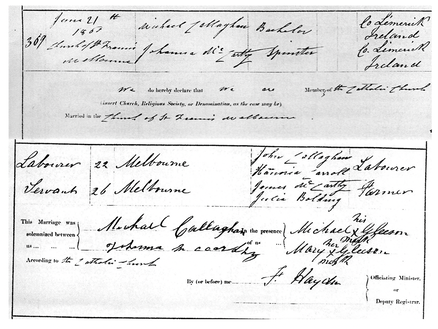

Marriage: 21 Jun 1860, Church of St. Francis, Melbourne, Australia

Children: Honora Mary (1863-1946)

John Francis (1865-1941)

James Michael (1867-1940)

William Aloysius (1869-1951)

The name Callaghan comes from Ceallachain, King of Munster, who was the Eóganachta King of Munster from AD 935 until 954. The personal name Cellach means ‘bright-headed.’ The principal Munster sept of the name Callaghan were lords of Cineál Aodha in South Cork originally. This area is west of Mallow along the Blackwater River valley. The family were dispossessed of their ancestral home and 24,000 acres by the Cromwellian Plantation and settled in East Clare.

The O'Callaghan land near Mallow, forfeited by Donough O'Callaghan after the Irish rebellion of 1641, came into the hands of a family called Longfield or Longueville, who built a 20-bedroom Georgian mansion there. In a twist of history, 500 acres of the ancient O'Callaghan land returned to O'Callaghan hands in the twentieth century, when Longueville House was bought by a descendant of Donough O'Callaghan. The ancestral estate of the O'Callaghans, now a luxury hotel, is owned by William O'Callaghan. In 1994, Don Juan O'Callaghan of Tortosa was recognized by the Genealogical Office as the senior descendant in the male line of the last inaugurated O'Callaghan. The Callaghan family motto is Fidus et Audax—"Faithful and Bold.”

The McCarthy Clan also claims descent from Ceallachain as well, but through his grandson Carthach, who was lord of Eoghannacht and was killed by the Lonergans in the year 1045. The clans had been displaced from Cashel during the Norman invasions and had settled in southwest Ireland, mostly near Mallow, in Cork, in an area known as Pobul I Callaghan. The McCarthy motto is Forti et tibeli nihil difficile, which means “Nothing is difficult to the brave and faithful.”

According to his obituary, Michael A (probably for Aloysius) Callaghan was born in Charleville, Co. Cork. Charleville was a fair town on the Cork/Limerick border. His death certificate and tombstone say his birth date was April 10, 1832, but that is incorrect. According to his baptismal certificate and the ship’s record of his immigration to Australia, he was born and baptized in 1838. His daughter Nora, who gave the information for the death certificate, must have assumed Michael was older than his wife Johanna.

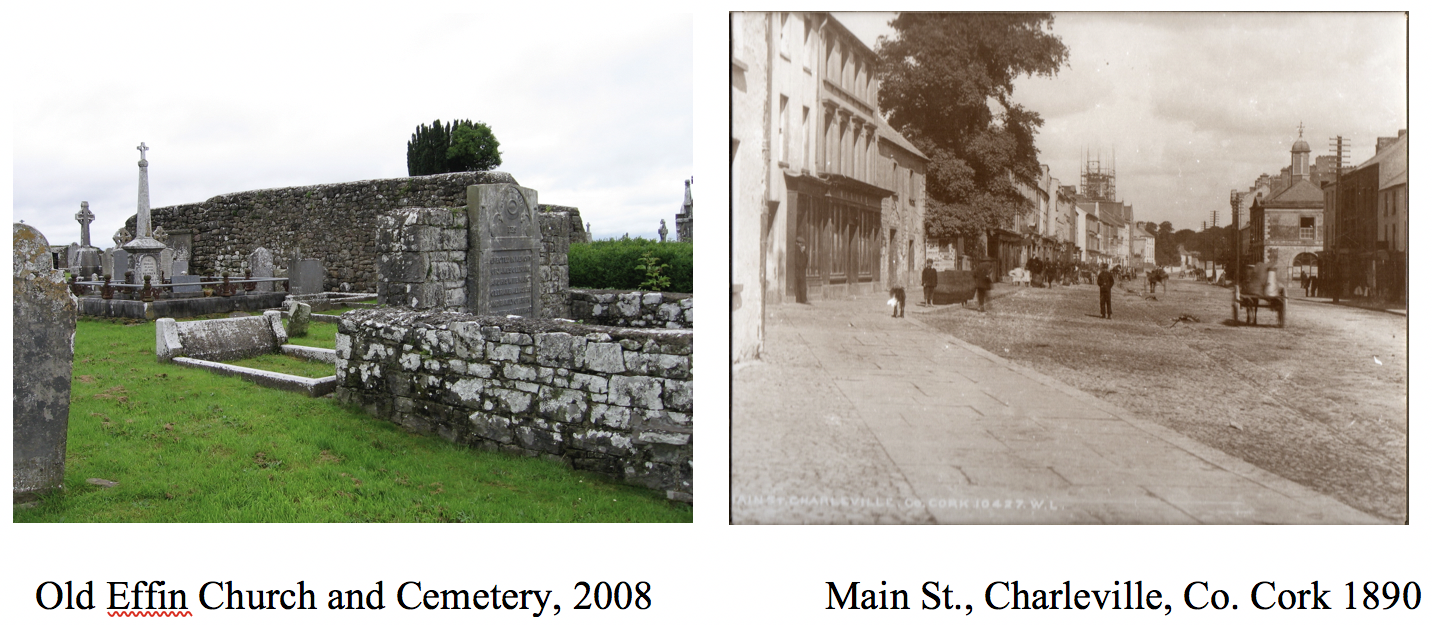

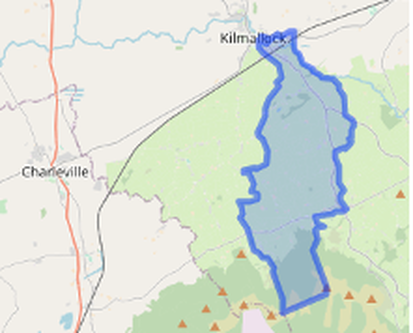

Michael was born on April 10, 1838, to John Callaghan and Honora Carroll. He was the second of seven children, with four brothers and two sisters. He was likely named after his maternal grandfather, Michael Carroll. According to his obituary, he was born in Charleville, Cork, but his marriage certificate says he was baptized in Effin, Limerick. Effin is a small township of 737 acres, halfway between Charleville and Kilmallock. This was likely his mother's home parish as there are several Carrolls buried there. Land records show that Michael was most likely born and raised in nearby Kilbreedy Minor, Mount Blakeney.

Death: 9 Aug 1920, Rio Vista, CA

Burial: St. Joseph's Cemetery, Rio Vista

Father: John Callaghan

Mother: Hanora Carroll

Spouse: Johanna McCarthy

Birth: 29 Sep 1833, Co Limerick, Ireland

Death: 9 Apr 1909, Rio Vista, CA

Father: James McCarthy

Mother: Julia Boland

Marriage: 21 Jun 1860, Church of St. Francis, Melbourne, Australia

Children: Honora Mary (1863-1946)

John Francis (1865-1941)

James Michael (1867-1940)

William Aloysius (1869-1951)

The name Callaghan comes from Ceallachain, King of Munster, who was the Eóganachta King of Munster from AD 935 until 954. The personal name Cellach means ‘bright-headed.’ The principal Munster sept of the name Callaghan were lords of Cineál Aodha in South Cork originally. This area is west of Mallow along the Blackwater River valley. The family were dispossessed of their ancestral home and 24,000 acres by the Cromwellian Plantation and settled in East Clare.

The O'Callaghan land near Mallow, forfeited by Donough O'Callaghan after the Irish rebellion of 1641, came into the hands of a family called Longfield or Longueville, who built a 20-bedroom Georgian mansion there. In a twist of history, 500 acres of the ancient O'Callaghan land returned to O'Callaghan hands in the twentieth century, when Longueville House was bought by a descendant of Donough O'Callaghan. The ancestral estate of the O'Callaghans, now a luxury hotel, is owned by William O'Callaghan. In 1994, Don Juan O'Callaghan of Tortosa was recognized by the Genealogical Office as the senior descendant in the male line of the last inaugurated O'Callaghan. The Callaghan family motto is Fidus et Audax—"Faithful and Bold.”

The McCarthy Clan also claims descent from Ceallachain as well, but through his grandson Carthach, who was lord of Eoghannacht and was killed by the Lonergans in the year 1045. The clans had been displaced from Cashel during the Norman invasions and had settled in southwest Ireland, mostly near Mallow, in Cork, in an area known as Pobul I Callaghan. The McCarthy motto is Forti et tibeli nihil difficile, which means “Nothing is difficult to the brave and faithful.”

According to his obituary, Michael A (probably for Aloysius) Callaghan was born in Charleville, Co. Cork. Charleville was a fair town on the Cork/Limerick border. His death certificate and tombstone say his birth date was April 10, 1832, but that is incorrect. According to his baptismal certificate and the ship’s record of his immigration to Australia, he was born and baptized in 1838. His daughter Nora, who gave the information for the death certificate, must have assumed Michael was older than his wife Johanna.

Michael was born on April 10, 1838, to John Callaghan and Honora Carroll. He was the second of seven children, with four brothers and two sisters. He was likely named after his maternal grandfather, Michael Carroll. According to his obituary, he was born in Charleville, Cork, but his marriage certificate says he was baptized in Effin, Limerick. Effin is a small township of 737 acres, halfway between Charleville and Kilmallock. This was likely his mother's home parish as there are several Carrolls buried there. Land records show that Michael was most likely born and raised in nearby Kilbreedy Minor, Mount Blakeney.

Little is known of Michael's early life. According to the 1900, 1910, and 1920 Censuses, Michael and Johanna immigrated to America in 1854, but this was incorrect. Also incorrect was family lore that Michael and Johanna had sailed from Ireland to America and that their first child, John Francis, had been born aboard ship while passing Australia. In fact, Michael and Johanna did not meet in Ireland, John was not their eldest child, nor was he born aboard ship.

Michael would have had several cousins his own age, especially among the Carrolls. They all would have done work on the farms, but they would have also attended school—though not in the Hedge Schools. That name would have been anachronistic by his father’s time and students would not have been taught hiding among the hedges. The more correct term would be “pay schools,” as the teachers would have been paid a nominal fee by the families. Classes would have been taught in a variety of locations—anywhere from a chapel or stone house to a mud hut, a cow barn, or in a cemetery. There were over 300 pay schools in Limerick by 1823. The curriculum would have included reading, writing, and arithmetic. Reading and writing would usually be in English, but sometimes in Irish, especially in West Limerick and Kerry. Latin and religion would be taught before mass on Sundays. County Kerry was well-known for its Latin school. Limerick was known for its math curriculum, where some of the teachers were also surveyors.

In 1843, when Michael was only five years old, his family was evicted from the land they had lived on for at least a century. His father fought the eviction for two years. Michael saw him go to jail several times and saw his Carroll uncles and cousins come to his father’s defense, sometimes violently. By the end, the family was living in a mud and stick house on a neighbor’s land. Then the Blight struck.

The Great Famine (An Gorta Mor) was the defining event of Michael’s young life. The whole family survived, but just barely. His uncle James Carroll took them in as subtenants in Effin, where they rented a stone house just behind the churchyard and near an ancient holy well. They struggled there for a dozen years. The McCarthys in nearby Ballingaddy were not so lucky.

Michael would have had several cousins his own age, especially among the Carrolls. They all would have done work on the farms, but they would have also attended school—though not in the Hedge Schools. That name would have been anachronistic by his father’s time and students would not have been taught hiding among the hedges. The more correct term would be “pay schools,” as the teachers would have been paid a nominal fee by the families. Classes would have been taught in a variety of locations—anywhere from a chapel or stone house to a mud hut, a cow barn, or in a cemetery. There were over 300 pay schools in Limerick by 1823. The curriculum would have included reading, writing, and arithmetic. Reading and writing would usually be in English, but sometimes in Irish, especially in West Limerick and Kerry. Latin and religion would be taught before mass on Sundays. County Kerry was well-known for its Latin school. Limerick was known for its math curriculum, where some of the teachers were also surveyors.

In 1843, when Michael was only five years old, his family was evicted from the land they had lived on for at least a century. His father fought the eviction for two years. Michael saw him go to jail several times and saw his Carroll uncles and cousins come to his father’s defense, sometimes violently. By the end, the family was living in a mud and stick house on a neighbor’s land. Then the Blight struck.

The Great Famine (An Gorta Mor) was the defining event of Michael’s young life. The whole family survived, but just barely. His uncle James Carroll took them in as subtenants in Effin, where they rented a stone house just behind the churchyard and near an ancient holy well. They struggled there for a dozen years. The McCarthys in nearby Ballingaddy were not so lucky.

Johanna McCarthy was born on September 29, 1833, in Ballingaddy Parish, Grague (or Gragenn) townland. He parents were James McCarthy and Julia Boland (though Julia’s name was reported as Bolyn, Bolding, and Roland in different records). Kilfanane church records indicate that Johanna had a sister named Honora, born in 1835 in Ballinanima, near Grague. James was a small farmer who only tenanted 9 acres on the De Lacy Smith estate. With such a small farm, they likely lived in a bothán and always on the edge of survival. Johanna’s parents were among those who died in the Famine, though we do not know exactly when, and a teenaged Johanna ended up in the Kilmallock Poor Law Union Workhouse.

Workhouse life was difficult and demeaning, and few Irishmen would enter by choice. Here is a description of the daily adult routine from the Irish Family Research Center:

Often children over the age of 12 were boarded out to families within the community, but during the Famine, there were more orphans than boarding families could handle.

With the Workhouses overflowing, the Poor Law Unions had to seek some relief, and emigration seemed to be the way. The Colonial Land and Emigration Commission had run a scheme since 1832 wherein they provided free passage to any British colony. Australia, in particular, had a gender imbalance and needed women. The Workhouses had the opposite imbalance. In 1848, the Children’s Apprenticeship Board was formed to organize and transport any teenage girl orphans in Ireland to Australia to serve as domestic servants. The goal was to emigrate 4000 girls from Ireland to provide economic relief to the Union. Any relief to the girls was a happy (and—as far as the Governance was concerned— unnecessary) coincidence. To be eligible for free fare, the girls had to be famine orphans and have been living in a Workhouse for at least a year. They gathered 20 shiploads of girls. Few of them had any choice about whether they would go or not.

According to Chris O’Mahony’s Emigration from the Workhouses of the Mid-West, 1848-1859,

The first ship, Earl Grey, arrived in Sydney on October 16, 1848. On May 17, 1849, the last of the ships, the 124-foot, 518-ton barque Elgin set sail with 195 of girls—including Johanna McCarthy—plus 30 paying passengers and two dozen crewmen. (The passenger list can be seen at http://www.theshipslist.com/ships/australia/elgin1849.shtml.) They reached Adelaide, South Australia, on September 10th. The trip took over 18 weeks with 250 people packed into a 124-foot ship. The voyage most likely included just a handful of stops, though the girls would not have been allowed off. Despite the rigors of the trip, The South Australian Register reported that “the female orphans on board the Elgin expressed themselves highly satisfied with their treatment, and the captain says he has not a fault to find with the young women.”

Once in Adelaide, there was a significant delay in job placement. According to the report to the Board by M. Moorhouse, the secretary to the Board:

Without job placement, the women would have been housed in another workhouse until employment was arranged. Description of this new “asylum” given in the November 1850 Report to the Children’s Apprenticeship Board as follows:

The Famine Orphan System proved unpopular, and the Australian papers disparaged the new immigrants, describing the orphans as follows:

Workhouse life was difficult and demeaning, and few Irishmen would enter by choice. Here is a description of the daily adult routine from the Irish Family Research Center:

- Inmates were awoken by the sound of the Workhouse bell at 6am each day. The Workhouse Master then took a "roll-call" at 6.30 a.m. just before breakfast. Breakfast usually consisted of a bowl of the cheapest porridge/grain with buttermilk (which was cheaper than normal milk). Work commenced at 7am and inmates were required to work through to noon when they were allowed between 1/2 and one hour for lunch. Lunch usually consisted of a pint of buttermilk and a piece of black bread. Inmates would continue working from 1 p.m. until 6 p.m. Dinner was served between 6.30 and 7 p.m. and often consisted of potatoes and Indian meal. As you may have gathered, buttermilk was given with everything. Soup was also given during the winter months. Fruit may have only been given at Christmas and Easter and was usually a gift from one of the key residents of the local town (e.g., the doctor's wife). Meat was bought, but was usually kept for the Workhouse Master, Matron and his key staff. Lights out at 8 p.m.

- Punishments were very harsh. An inmate who refused to carry out his work duties would be given 24 lashes plus no dinner for one week. An inmate who used abusive language would be put into solitary confinement plus no dinner for one week or longer. Female inmates who breached rules could often be forced to break stones for one week. After all, workhouse life was not meant to be pleasant.

Often children over the age of 12 were boarded out to families within the community, but during the Famine, there were more orphans than boarding families could handle.

With the Workhouses overflowing, the Poor Law Unions had to seek some relief, and emigration seemed to be the way. The Colonial Land and Emigration Commission had run a scheme since 1832 wherein they provided free passage to any British colony. Australia, in particular, had a gender imbalance and needed women. The Workhouses had the opposite imbalance. In 1848, the Children’s Apprenticeship Board was formed to organize and transport any teenage girl orphans in Ireland to Australia to serve as domestic servants. The goal was to emigrate 4000 girls from Ireland to provide economic relief to the Union. Any relief to the girls was a happy (and—as far as the Governance was concerned— unnecessary) coincidence. To be eligible for free fare, the girls had to be famine orphans and have been living in a Workhouse for at least a year. They gathered 20 shiploads of girls. Few of them had any choice about whether they would go or not.

According to Chris O’Mahony’s Emigration from the Workhouses of the Mid-West, 1848-1859,

- Those responsible for this scheme were sensitive to the special features of the undertaking and proceeded with great propriety. They wanted healthy, well- behaved, literate and industrious candidates, and took steps to ensure these standards were observed in selection and maintained later. Thus, an officer was chosen to approve the suitability of candidates proposed by the local boards of guardians. Each applicant was medically examined and vaccinated. Standards were set in food and clothing for the 100-day voyage. Each ship was to have a doctor, a matron and a teacher on board. 'Moral religious superintendence' was stressed, to such an extent that ships chartered to carry the orphans were not allowed to take male passengers.

The first ship, Earl Grey, arrived in Sydney on October 16, 1848. On May 17, 1849, the last of the ships, the 124-foot, 518-ton barque Elgin set sail with 195 of girls—including Johanna McCarthy—plus 30 paying passengers and two dozen crewmen. (The passenger list can be seen at http://www.theshipslist.com/ships/australia/elgin1849.shtml.) They reached Adelaide, South Australia, on September 10th. The trip took over 18 weeks with 250 people packed into a 124-foot ship. The voyage most likely included just a handful of stops, though the girls would not have been allowed off. Despite the rigors of the trip, The South Australian Register reported that “the female orphans on board the Elgin expressed themselves highly satisfied with their treatment, and the captain says he has not a fault to find with the young women.”

Once in Adelaide, there was a significant delay in job placement. According to the report to the Board by M. Moorhouse, the secretary to the Board:

- The October 13th Report of the Board mentioned that "... The orphans per the Elgin arrived on the 10th September last, but are meeting with situations at a slow rate. The vessel has been nearly one month in Port, and there are at this date, 109 unhired. ..."

Without job placement, the women would have been housed in another workhouse until employment was arranged. Description of this new “asylum” given in the November 1850 Report to the Children’s Apprenticeship Board as follows:

- …this asylum by the persons officially connected with its management, shows it to have been most insidiously and improperly conducted and different in all respects from such an institution as might with safety have been opened for the casual reception of these young women in the event of their becoming destitute.

- It is not to be regarded with surprise that the worse disposed among the emigrants should choose to resort to the security of their companions in an asylum of this nature rather than submit to the drudgery and loneliness of a servants life in the family of a settler: that they should refuse eligible situations,[feigning] inability to work, that having gone into service they should behave themselves insolently and disobediently, and show an unwillingness to learn and perform their duty and that on remonstrance from their employers they should throw up their service and repair to the asylum with their wages already earned in their profession. The present dispatch contains much evidence in proof of this nefarious tendency of the depot, in the statements of settlers who were examined by the Apprenticeship Board as to the character and conduct of particular emigrants and the Apprenticeship Board observe in their report that "numberless instances of the same kind might be added" to those accounted.

The Famine Orphan System proved unpopular, and the Australian papers disparaged the new immigrants, describing the orphans as follows:

- It is notorious that when a girl from the age of 14 to 18 is for the first time taken into service in a family in the Mother Country, she has to acquire from teaching a knowledge of her household duties and it was to be hoped that in the state of the demand for female domestics represented as existing in the Australian Colonies, the Irish orphan girls, being naturally quick and apt to learn, would, with patience and forbearance on the part of their employers, acquire a knowledge of their duties and that if left to feel dependent on their own obedience and good behavior, they would hold steadily to their engagements with their employers and so justify the prophecy which suggested this class of emigrants as likely to supply the wants of the settled in the Australian Colonies.

- …the settlers who have engaged Irish orphans have made many complaints of the inconvenience suffered from the girls leaving their situations without the least provocation, some fancied they were too far from town, some who were in town thought they would like the country better, others wished to be nearer those from the same union in Ireland, others would not milk, others again would not wash.

Johanna did find employment. It is not known where Johanna was initially placed or what jobs she might have had, but she was working for the Reverend Thomas Quinton Stow at Felix Stow, Paynham (outside of Adelaide) when Michael arrived nine years later.

Thomas Quinton Stow arrived in South Australia in the Hartley in 1837 and was the first nonconformist minister to take up pastoral duties. He bought land east of Adelaide and is believed to have named it by combining the Latin felix (happy or lucky) with the Anglo-Saxon stow - ‘place’. On a document dealing with the land in 1851, there is the signature ‘Thomas Quinton Stow, Felixstow, May 19th 1851’ and a memorial of a conveyance of portion of section 306 to Rev. T.Q. Stow in July 1851 refers to ‘Rev. Thomas Quinton Stow of Felixstow.’ The domain of the Stow’s (a name that had already become a household word in South Australia) was situated to the left of the road from Adelaide, on the banks of the Torrens, about half a mile beyond the village and not far from the German hamlet of Klemzig.

The vineyard upon the estate was the property of Augustine Stow. The first planting was done in 1852 when 4½ acres were put in. He also has an orangery. In 1854, about 200 trees were planted at 15 feet apart, but in the dry summer, that followed, little progress was made… A creek ran through the western portion of the grounds to the Torrens. This had been diverted from its original tortuous course and straightened. Adjacent to this property was a ten acre block belonging to R.I. Stow and Wycliff Stow, on about eight acres of which vines have been planted.

Thomas Quinton Stow arrived in South Australia in the Hartley in 1837 and was the first nonconformist minister to take up pastoral duties. He bought land east of Adelaide and is believed to have named it by combining the Latin felix (happy or lucky) with the Anglo-Saxon stow - ‘place’. On a document dealing with the land in 1851, there is the signature ‘Thomas Quinton Stow, Felixstow, May 19th 1851’ and a memorial of a conveyance of portion of section 306 to Rev. T.Q. Stow in July 1851 refers to ‘Rev. Thomas Quinton Stow of Felixstow.’ The domain of the Stow’s (a name that had already become a household word in South Australia) was situated to the left of the road from Adelaide, on the banks of the Torrens, about half a mile beyond the village and not far from the German hamlet of Klemzig.

The vineyard upon the estate was the property of Augustine Stow. The first planting was done in 1852 when 4½ acres were put in. He also has an orangery. In 1854, about 200 trees were planted at 15 feet apart, but in the dry summer, that followed, little progress was made… A creek ran through the western portion of the grounds to the Torrens. This had been diverted from its original tortuous course and straightened. Adjacent to this property was a ten acre block belonging to R.I. Stow and Wycliff Stow, on about eight acres of which vines have been planted.

Back in Ireland, the Callaghans survived. But even after the Famine was considered over (1849 or 1852, depending on who you take as the source), the crops were thin of a family of eight. While the potato blight seemed to be under control, crops still occasionally failed and 1858 saw a return to famine levels. The clause in the Poor Law Act which had allowed for the government support of emigration came into effect again, this time to transport men to Australia where they were needed because so many farm hands had left the fields during the Gold Rush of 1852-3. Another round of the crop failures, political unrest, the rise of Irish Republican Brotherhood, and the death of Michael’s mother Nora likely helped his father John decide to emigrate the family.

In July of 1858, a 19-year-old Michael Callaghan boarded the Bee—a 1200-ton ship built in Boston in 1853—with his father and siblings, bound for Australia. They arrived in Adelaide, South Australia, on October 9, 1858, after a journey of 98 days during which six people died (five of them children under 1) and six more were born aboard the ship. While aboard ship, Michael and his brothers took classes in reading, writing and arithmetic from a schoolmaster who had his own emigration subsidized by holding 57 days worth of classes to some 100 children and adults.

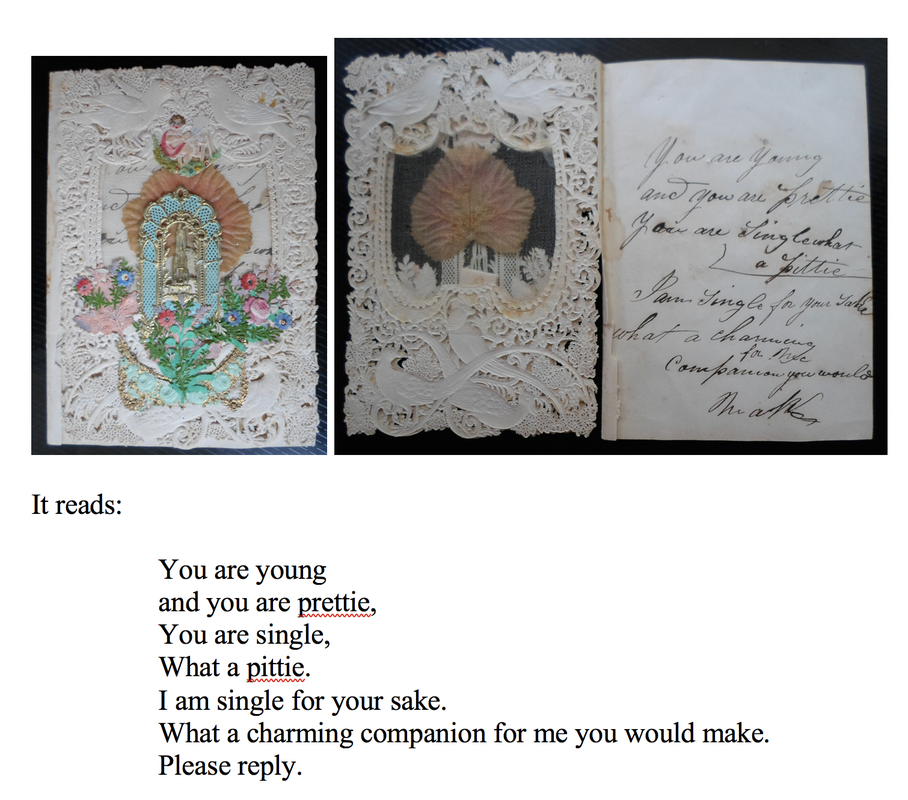

One complaint about the Nominee program to South Australia was that it was hard to keep the immigrants in Adelaide. One employer stated in 1859 that, of the 40 immigrants who had come from England the previous summer, only one remained. The rest had moved to Melbourne. Melbourne had better pay and more employment available. Michael moved to Melbourne to ensure his future and wrote to Johanna to propose marriage. The letter below was kept in the family and was given to Kevin Quattrin by Arlene Callaghan, widow of Michael’s grandson Young Bill.

In July of 1858, a 19-year-old Michael Callaghan boarded the Bee—a 1200-ton ship built in Boston in 1853—with his father and siblings, bound for Australia. They arrived in Adelaide, South Australia, on October 9, 1858, after a journey of 98 days during which six people died (five of them children under 1) and six more were born aboard the ship. While aboard ship, Michael and his brothers took classes in reading, writing and arithmetic from a schoolmaster who had his own emigration subsidized by holding 57 days worth of classes to some 100 children and adults.

One complaint about the Nominee program to South Australia was that it was hard to keep the immigrants in Adelaide. One employer stated in 1859 that, of the 40 immigrants who had come from England the previous summer, only one remained. The rest had moved to Melbourne. Melbourne had better pay and more employment available. Michael moved to Melbourne to ensure his future and wrote to Johanna to propose marriage. The letter below was kept in the family and was given to Kevin Quattrin by Arlene Callaghan, widow of Michael’s grandson Young Bill.

She replied yes, and they married on June 21, 1860, at the Church of St. Francis, Melbourne. Michael and Johanna had two children in Melbourne. Nora was born on Bouverie Street, Carlton, in 1863, and John was born on Leicester Street, North Melbourne, in 1865. According to Johanna’s obituary and the 1900 Census, three other children did not survive childhood, but birth, baptism, or death certificates for them have not be found in Australia or California.

The town of Melbourne was founded by the Port Philip Association in 1835 by treaty with the Wurundjeri elders. That treaty was annulled by the government of New South Wales at the time, but the settlers were allowed to stay. In July 1851, agitation by the Port Phillip settlers led to the establishment of Victoria as a separate colony. At the time, the white population of the whole Port Phillip District was still only 77,000, and only 23,000 people lived in Melbourne. Melbourne had already become a center of Australia's wool export trade. The discovery of gold would change all that.

A huge influx of people flooded Victoria, most of them arriving by sea at Melbourne. The town's population doubled within a year. In 1852, 75,000 people arrived in the colony and this, combined with a very high birthrate, led to rapid population growth. As the easy gold ran out, many of these people flooded into Melbourne or became a pool of unemployed in cities around Ballarat and Bendigo. There arose a huge wave of social unrest urging the opening of the lands in rural Victoria for small yeoman farming. The concurrent dispossession of the Aboriginal populations in those areas of inland Victoria which had not already been cleared for sheep runs was equally rapid, and the lands were opened. Still, by 1857, Melbourne had a population of 500,000.

The accelerated population growth and the enormous wealth of the goldfields fueled a boom which lasted for forty years, and ushered in the era known as “Marvelous Melbourne.” The city spread eastwards and northwards over the surrounding flat grasslands, and southwards down the eastern shore of Port Phillip. Wealthy new suburbs like South Yarra, Toorak, Kew, and Malvern grew up, while the working classes settled in Richmond, Collingwood, and Fitzroy.

The influx of educated gold seekers from England led to rapid growth of schools, churches, learned societies, libraries and art galleries. Australia's first telegraph line was erected between Melbourne and Williamstown in 1853. The first railway in Australia was built in Melbourne in 1854 between the city and Port Melbourne, then known as Sandridge. That same year, the government offered four religious groups land on which to build schools. These included the Wesleyan Methodist Church and the Anglican Church. These resulted in Wesley College and Melbourne Grammar School being built in St Kilda Road a few years later. The University of Melbourne was founded in 1855, and the State Library of Victoria in 1856. The foundation stone of St Patrick's Catholic Cathedral was laid in 1858. The Philosophical Institute of Victoria received a Royal Charter in 1859 and became the Royal Society of Victoria. In 1860, this Royal Society assembled Victoria's only organized attempt at inland exploration, the Burke and Wills expedition, with other exploration being more ad hoc.

Victoria suffered from an acute labor shortage despite its steady influx of migrants, and this pushed up wages until they were the highest in the world. Victoria was known as "the working man's paradise" in these years. The Stonemasons Union won the eight-hour day in 1856 and celebrated by building the enormous Melbourne Trades Hall in Carlton. By the time Michael and Johanna settled in Carlton, Melbourne had become quite the bustling city.

Michael and Johanna had two children in Melbourne. Nora was born on January 3, 1863, on Bouverie Street, in Carlton. John was born on May 21, 1865, on Leicester Street in North Melbourne. According to Johanna’s obituary and the 1900 Census, three other children did not survive childhood, but neither birth, baptism, nor death certificates for them have been found in Australia or California.

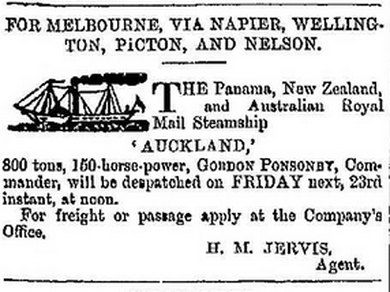

By June of 1865, the family had decided to immigrate to California. Michael and Johanna were probably enticed by the combination of available land through the Homestead Act and the ending of the Civil War. After five years in an expanding Melbourne, they likely preferred farm-living to city-living. Despite having a five-week-old baby, they boarded a steamer for the trans-Pacific crossing to Panama. Michael would never see his father or siblings again. It would not be until 2022—137 years later—that two of the branches would reconnect when Kevin Quattrin found a DNA connection to Virginia Loy, a great-great-granddaughter of Michael's sister Mary Callaghan Burns and reached out through email.

Prior to the 1860s, the Pacific crossing was made by clipper ship and could take as much as ten weeks, depending on the weather. But steamship travel was much more common after 1860. Supposedly, ships of the Pacific Mail Company usually took 45 days for the crossing, with stops in Honolulu, Tahiti, and Panama. From Panama, an immigrant could catch another ship of the Pacific Mail Line up the West Coast to San Diego, San Francisco, and Portland. The name of the ship and the dates of departure and arrival are not known for certain, but a Michael Callaghan is listed in the Victoria Outward Bound Index, on the RMS Auckland, bound for Auckland, New Zealand, on June 23, 1865—two days after John’s baptism. This Michael Callaghan’s age is wrong to be our Michael, but ages were often not well known by Irish immigrants. It was not a priority. The Auckland would have been similar to the reconstructed HMS Warrior, pictured below.

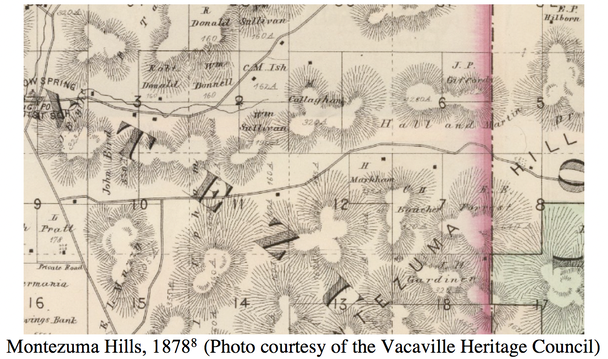

Initially, Michael and family lived at 7th and Minna Streets in San Francisco, where Michael worked as a laborer while Johanna took in washing. Nadine used to say “3rd and Minna” whenever she wanted to refer to the poor, rundown part of town south of Market Street. She did not know at the time that her ancestors had lived in the area. A third child, James (named after his McCarthy grandfather and Callaghan uncle), was born in San Francisco in mid-September 1867. According to the Land Grant records, the family moved two weeks later to the Ranch Montezuma Hills on the Sacramento Delta on October 2, 1867. A fourth child, William, was born there in 1869.

The 1879 History of Solano County reads:

- By far the major portion of this township consists of large steep hills, known as the Montezuma Hills, from which the township derives it name. To one traveling over the level plains of the northern townships, these hills seem like small mountains, and it is a great surprise to strangers to learn that they are cultivated…

- The trade winds sweep over this township with great force, bearing with it more or less dampness. It is very healthful throughout, even on the marsh land. The climate cannot be called delightful, although it is in California, but it is doubtless preferable for many reasons to the warmer sections further north.

The 1912 History of Solano and Napa Counties notes that Montezuma Township comprised a tract of treeless rolling hills for its northern sections and marshlands in the southern. It was rich and verdant, and “a vast sea of green [wild oats] waved in the almost eternal winds that swept and sweep over the country.” Summer temperatures often climb over 100 degrees Fahrenheit , and winters bring heavy rains, which could also fall in the summer. Dolores remembered visiting in the summer and having to stay at the hotel in Rio Vista because the road to the Ranch was impassible due to the mud.

The family homesteaded 160 acres of public land in Montezuma Township. The Homestead Act allowed for people to settle on public land and gain title after a time if they improved the land. They were required to sink a well, build a house, and bring 75 percent of the land under cultivation. According to witnesses William Jubb (a local farmer) and George Smith (a boatman) who filed statements as part of Michael pre-emption proof in 1870, he and the family had lived on the land continuously for three year and he had built a 12-foot by 24-foot house, a 24=foot by36-foot barn, a corral, a granary, and outhouses, as well as sinking a “good well.” The additions were worth $800. They also noted that he had cultivated all 160 acres with wheat and barley.

Because of the climate, the agricultural cycle in California was different than in Ireland or anywhere in the Midwest or East. Elsewhere, winter meant frozen ground, so plowing and planting had to occur in the Spring and harvest happened in August. In California, the ground is hard in the August after being baked all summer. Plowing and planting for wheat and barley happened in September and October once the rains began and softened the ground. Harvest occurred in late June and Early July. This also paired well with sheep rearing. Breeding season is in November, after the sowing of wheat was done. Birthing and shearing occurred in May, before harvest time. Later in Michael’s life, the addition of corn and beans could be added with planting in Spring and harvesting in late August. This allowed for a second growing season.

Alan Freese, a descendant of neighbor Eugene Sullivan, grew up on a farm in the Montezuma Hills. Later, he took over his ancestor’s’ ranch and rented the Upper Ranch from the Callaghans. He described farm life in the area:

The nature of the farming in the Montezuma Hills was and still is not labor intense. The vegetable and fruit crops are labor intense as you well know. My mom said they had a Chinese house boy as well as a choreman. Grain harvest required extra help. The harvest crew consisted of 4 and sometimes 5. A mule skinner, a header tender and two men in the dog house—that is, where they would handle the grain and sack it. They would fill four sacks and then drop them in the field. I remember visiting and riding on the combine in the dog house. It was the worst place, hot and dusty with grain chaff. Probably called that because it was the worst job. When they put engines on the combine they might have another man to lube and tend to the moving parts. The tractor replaced the horses, and the operator was referred to as a Cat Skinner. The tractors were Caterpillars that started in Stockton by the Holt family.

They hired two or three men during harvest and furnished room and board. The crew ate with the family. These men would follow the harvest and were white. There were quite a few men from the dust bowl states. Of course, right after harvesting the field they would pick up the sacked grain and load it on a flatbed truck. A wheat sack could weigh 120 -130 pounds. Now one combine operator can harvest more acres in a day than they could in week. The grain is all bulk. No more sacks

Shearing has always been done by professionals. The system hasn’t changed other than power clippers came in to replace the old hand shears.

Regarding the similarities of Iowa farms, the Montezuma Hills farming would be like Iowa. No irrigation, relying on rainfall. Iowa grows corn, soybeans and these are crops that are summer grown. Cattle feedlots and pork production are prevalent because of corn. So many farm families in that part of the country have other jobs. School teachers and local Civil servant jobs are popular.

Another requirement for Homesteading was that the head of house become naturalized if not already a citizen. Michael carried out all the improvements and became a citizen on June 5, 1871, in the San Francisco District Court. In 1872, he was able to claim the 160 acres from the Illinois Industrial University.

The 1870 non-population census gives a great deal of information about the ranch. It shows that the land was worth $3,200 and housed $300 worth of farm implements. The crop was 25 tons of hay and 1,000 bushels of wheat worth $1,000. They had two horses and two cows worth $500. Total value was $6,200. No wages were paid that year, meaning the family did all the work by themselves. For comparison, the adjacent, 160-acre Sullivan ranch was worth $4,800. William Sullivan had more livestock and paid $8,000 in wages. That ranch’s total value was $16,500.

In 1874, Michael purchased another 160 acres of adjacent land from E. J. Upham for $4,000. He kept accumulating small pieces of land—16 acres here, 40 acres there—until, by 1880, he owned 358 acres worth $10,000 and had $900 worth of livestock. The value of the previous year’s production was $5,500, and he had paid for 18 weeks of hired labor. He had produced 720 tons of hay and cultivated 50 acres of wheat. He now had 10 horses, 20 swine, two cows that produced 250 pounds of butter, 40 chickens that laid 200 eggs, and 7 sheep and 6 lambs that produced 21 pounds of wool.

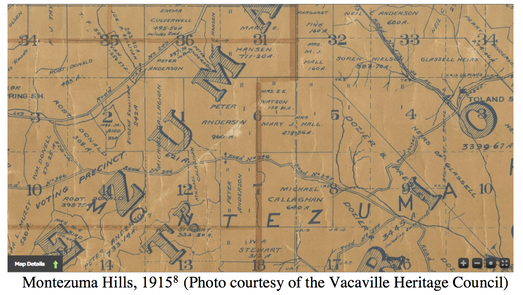

In 1883, Michael purchased the 640-acre Edwin Forrest Ranch and was renting the Stephen Markham Ranch, adjacent to the original Callaghan Ranch to the south. This gave him better road access to County Road #346, which ran from Toland Landing to Birds Landing. County Road #346 is now known as Montezuma Hills Road, but it was known as Callaghan Ranch Road on the 1920 Census. According to McKenney’s Directory of 1884-5, Michael owned or leased a ranch of 1276 acres. In the article about John’s wedding in 1890, Michael was referred to as “Mr. M. Callaghan, Esq., the extensive and well-to-do farmer of the Montezuma Hills” and the Home Ranch house as an “elegant and spacious home.”

The original ranch and the Stephen Markham property, which Michael purchased in May of 1891, were located halfway between Toland and Birds Landings. It became known as the Upper Ranch while the original was referred to as the Home Ranch. In 1897, John built a house on the Markham land, and Jim built a house on west half of the Lower Ranch section, which was at the bottom of Toland Grade. The two parts of the ranch were separated by part of the Peter Anderson Ranch.

Michael and Johanna lived on the Ranch for 40 years and, other than Michael’s trip to San Francisco to become a naturalized citizen on June 5, 1871, his occasional trip to Fairfield on business, and a vacation to St. Paul, Minnesota in September of 1895, they never seem to have gone anywhere else. Michael and Johanna rarely appeared in the local paper, but their children were often there. The family was active in the community, often serving as members of committees for dances and church faires at both St. Joseph’s Church in Rio Vista and St. Charles Borromeo in Collinsville. Michael’s biography does not appear in either of the county histories that were published in his lifetime, but that is not surprising since one had to pay to be in the books.

Michael and Johanna believed in education. Johanna enrolled her sons in St Mary’s College and her daughter in St. Gertrude’s Academy for Women. Michael served as one of three trustees for the Toland School District. In 1891, he was involved in trying to form a unified high school with the other four local school districts. One of the districts already had permission to form a high school, and the county school superintendent and all 15 trustee of the five districts were taken to court for forming another high school by an individual who believed that the change would force him to pay double taxes. The suit was dropped, but another plaintiff brought suit again in 1912. By this time, Michael had retired and his son Jim was on the Board. The plaintiff won and the boards were barred from mentioning a Toland unified high school. The Rio Vista Union High School was established anyway two years later.

Michael and Johanna believed in education. Johanna enrolled her sons in St Mary’s College and her daughter in St. Gertrude’s Academy for Women. Michael served as one of three trustees for the Toland School District. In 1891, he was involved in trying to form a unified high school with the other four local school districts. One of the districts already had permission to form a high school, and the county school superintendent and all 15 trustee of the five districts were taken to court for forming another high school by an individual who believed that the change would force him to pay double taxes. The suit was dropped, but another plaintiff brought suit again in 1912. By this time, Michael had retired and his son Jim was on the Board. The plaintiff won and the boards were barred from mentioning a Toland unified high school. The Rio Vista Union High School was established anyway two years later.

In 1899, Michael built a new two-story, stick-style Victorian house on the east half of the Lower Ranch, across the boundary in the Rio Vista Township. It became known as the Home Ranch thereafter. Michael, Johanna, Nora, and Bill moved in there with four ranch hands and their Japanese cook, Henry Saso. Bill moved back into the old Home Ranch when he married a year later.

No photos of Johanna are known to have survived. The description given of Michael in the 1892 Great Register describes him as 5-feet, 9-inches, with fair complexion, blue eyes, and grey hair. Only two possible photos of Michael have survived. The people in this Home Ranch photo from 1915 are most likely Michael and his daughter Nora Callaghan, but it cannot be confirmed. The photo of the man at the beginning of this biography might be Michael. It is a blow-up of the driver of the McCormack Reaper pictured below. The picture is from the 1890s, and Michael’s grandson Lester Callaghan had it on the wall in his garage for years. The people on the ground appear to be Lester’s parents and his uncle Bill.

Johanna died at the Home Ranch on April 9, 1909. She was 76 years old. Her obituary referred to her as a “highly respected resident of the Montezuma Hills” who died after “an illness of several months” (according to her death certificate, chronic pericarditis) that “the latest attack coupled with her advanced age would not yield to medical skill or the loving care of her husband and children.” She had many mourners, and several of the Andersons were pall-bearers.

Michael continued to live at the Home Ranch house for another ten years. Later in life, besides serving as a trustee of the Toland School District, Michael became more involved in St. Joseph’s Church. In September of 1911, he served as the sponsor to all the St. Gertrude Academy boys who were advanced for confirmation. Lester was one of those boys.

In 1919, with his health failing, Michael moved into Nora’s house in Rio Vista. Over the next year, he spent extended periods of time confined to his bed. On April 4, 1920, John’s daughters Ruth and Madelyn returned to town to celebrate Michael’s birthday. It was the last time they would see him.

Michael continued to live at the Home Ranch house for another ten years. Later in life, besides serving as a trustee of the Toland School District, Michael became more involved in St. Joseph’s Church. In September of 1911, he served as the sponsor to all the St. Gertrude Academy boys who were advanced for confirmation. Lester was one of those boys.

In 1919, with his health failing, Michael moved into Nora’s house in Rio Vista. Over the next year, he spent extended periods of time confined to his bed. On April 4, 1920, John’s daughters Ruth and Madelyn returned to town to celebrate Michael’s birthday. It was the last time they would see him.

Michael died on August 9, 1920, from chronic interstitial nephritis. He was 82 years old. His loving daughter Nora put up one of the largest monuments in the Rio Vista Catholic Cemetery, second only to the statue of Sister Mary Camillus, the founder of St. Gertrude’s Academy. His obituary referred to the “extensive land holdings which he had developed” and “a large circle of friends which was borne out by the representative people who attended his funeral.”

The estate Michael left behind was to be managed by Nora and Jim as his executors. It was worth approximately $80,000, which would be about $1.6 million in 2014 — not bad for a couple of famine refugees. The real estate was essentially divided equally. Nora received the east half of the Lower Ranch, including the 1899 house, and Jim received the east half, where he had built his home. John received the south half of the Upper Ranch, and Bill inherited the original Home Ranch. In accordance with Michael’s 1911 will, instead of direct ownership, John received a life interest in his 317 acres. The actual ownership of the land was in the names of John’s three children. Michael wanted the Ranch to stay in the family, and, since John had remarried after his first wife Ellen had died, Michael was concerned that the new marriage and John’s strained relationship with his children would interfere with that.

John contested Michael’s will—not over ownership of the Ranch, but over some $50,000 in cash, stocks, and bonds that Michael had had in joint accounts with Nora. The Inheritance Tax Appraiser determined that Michael had made a gift of all those funds to Nora because the funds had been moved out of the accounts and into new accounts in Nora’s name only before he died. It was likely done to avoid probate fees and inheritance taxes, but Nora does not seem to have given any of the funds directly to her brothers

Unknown at the time, the Montezuma Hills were situated over the largest natural gas field in California. Mineral rights have yielded millions of dollars in revenue to the family over the past 80 years, though income from this source tailed off significantly into the 21st Century. In the 1990s, Dolores’s share brought in between $1,500 and $2,000 per month. Members of the fourth generation of Anderson descent earned even more. By 2014, earnings had dropped to less than $200.

In 2012, the last fourth of the Ranch still in the family—the original Home Ranch—was leased to NextEra Energy (Florida Power and Light) for windmills to be built. Those windmills, fed by the “almost eternal winds,” yielded over $5 million in energy purchased by PG&E during the first year, with $200,000 of that income going to the family. Callaghan Ranch LLC was formed (with Kevin Quattrin as the managing partner) to handle the income and expenses of the property.

In 2018, an offer was made by the Flannery Associates to buy the property, but the cousins decided not to sell. Flannery Associates were buying up farms Solano County, and no one knew why or who they were. Two years later, Flannery upped their offer. The offer was good—$3 million and the cousins each got to retain the rights to the windmill income. The Woods brothers wanted to sell and forced the dissolution of the LLC. David Quattrin joined them. Soon after the sale, Duncan Moore died and his wife sold his share as well. Kevin and the Chase brothers still retain their ownership of the family ranch, but only time will tell for how long they can holdout. In 2021, Kevin accepted a new offer from Flannery to which it was just too good to say no. He exchanged the property for a house where his son Rudraigh Callaghan Quattrin could move when he married at the end of the year and started to raise the next generation. A year later, the Chase brothers reluctantly sold their share as well. The Ranch was finally gone from the family.

The estate Michael left behind was to be managed by Nora and Jim as his executors. It was worth approximately $80,000, which would be about $1.6 million in 2014 — not bad for a couple of famine refugees. The real estate was essentially divided equally. Nora received the east half of the Lower Ranch, including the 1899 house, and Jim received the east half, where he had built his home. John received the south half of the Upper Ranch, and Bill inherited the original Home Ranch. In accordance with Michael’s 1911 will, instead of direct ownership, John received a life interest in his 317 acres. The actual ownership of the land was in the names of John’s three children. Michael wanted the Ranch to stay in the family, and, since John had remarried after his first wife Ellen had died, Michael was concerned that the new marriage and John’s strained relationship with his children would interfere with that.

John contested Michael’s will—not over ownership of the Ranch, but over some $50,000 in cash, stocks, and bonds that Michael had had in joint accounts with Nora. The Inheritance Tax Appraiser determined that Michael had made a gift of all those funds to Nora because the funds had been moved out of the accounts and into new accounts in Nora’s name only before he died. It was likely done to avoid probate fees and inheritance taxes, but Nora does not seem to have given any of the funds directly to her brothers

Unknown at the time, the Montezuma Hills were situated over the largest natural gas field in California. Mineral rights have yielded millions of dollars in revenue to the family over the past 80 years, though income from this source tailed off significantly into the 21st Century. In the 1990s, Dolores’s share brought in between $1,500 and $2,000 per month. Members of the fourth generation of Anderson descent earned even more. By 2014, earnings had dropped to less than $200.

In 2012, the last fourth of the Ranch still in the family—the original Home Ranch—was leased to NextEra Energy (Florida Power and Light) for windmills to be built. Those windmills, fed by the “almost eternal winds,” yielded over $5 million in energy purchased by PG&E during the first year, with $200,000 of that income going to the family. Callaghan Ranch LLC was formed (with Kevin Quattrin as the managing partner) to handle the income and expenses of the property.

In 2018, an offer was made by the Flannery Associates to buy the property, but the cousins decided not to sell. Flannery Associates were buying up farms Solano County, and no one knew why or who they were. Two years later, Flannery upped their offer. The offer was good—$3 million and the cousins each got to retain the rights to the windmill income. The Woods brothers wanted to sell and forced the dissolution of the LLC. David Quattrin joined them. Soon after the sale, Duncan Moore died and his wife sold his share as well. Kevin and the Chase brothers still retain their ownership of the family ranch, but only time will tell for how long they can holdout. In 2021, Kevin accepted a new offer from Flannery to which it was just too good to say no. He exchanged the property for a house where his son Rudraigh Callaghan Quattrin could move when he married at the end of the year and started to raise the next generation. A year later, the Chase brothers reluctantly sold their share as well. The Ranch was finally gone from the family.

Michael and Johanna had long, adventurous lives. They lived through the Great Famine, dealt with eviction and relocation half way around the world where they found each other, and relocation again. Like the other Patriarch of the Family, Perbacco Quattrin, Michael saw the family transition from tenant farmer to landed gentry. They both experienced death up close—Michael through Famine and Andrea through War.

Michael and Johanna saw the birth of seven children and the loss of three of them in childhood, as well as the births of 12 grandchildren—and the loss of three of them in childhood as well. From Famine Orphan and indentured laborer to wealthy pillars of the community, they clung to each other through thick and thin, building a life for themselves and their children out of death, devastation, and displacement. That life served as a shining example and a beacon of hope through the generations, and Michael’s financial success helped the next six generations survive and thrive, ultimately providing a home for the seventh generation.

Michael and Johanna saw the birth of seven children and the loss of three of them in childhood, as well as the births of 12 grandchildren—and the loss of three of them in childhood as well. From Famine Orphan and indentured laborer to wealthy pillars of the community, they clung to each other through thick and thin, building a life for themselves and their children out of death, devastation, and displacement. That life served as a shining example and a beacon of hope through the generations, and Michael’s financial success helped the next six generations survive and thrive, ultimately providing a home for the seventh generation.