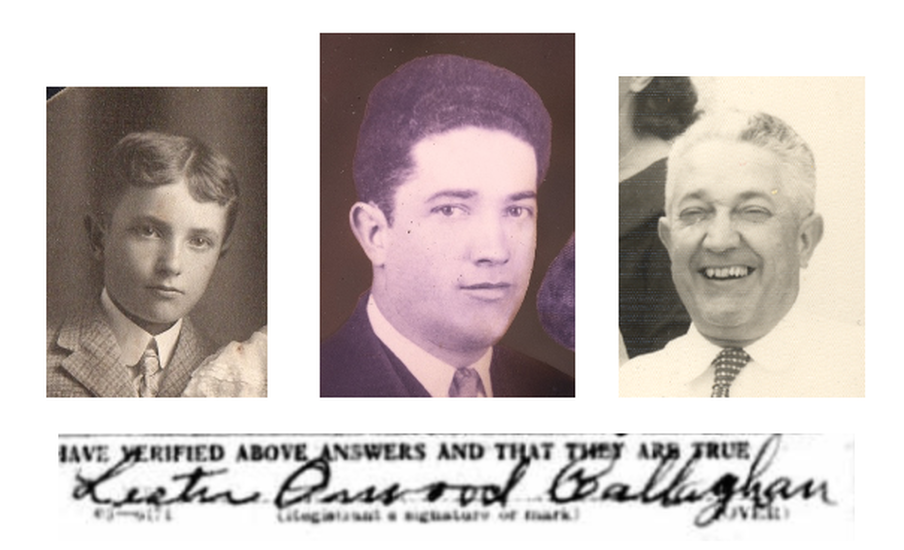

Lester Orwood Callaghan

Birth: 9 May 1898, Rio Vista, CA

Death: 31 Jul 1968, San Francisco, CA

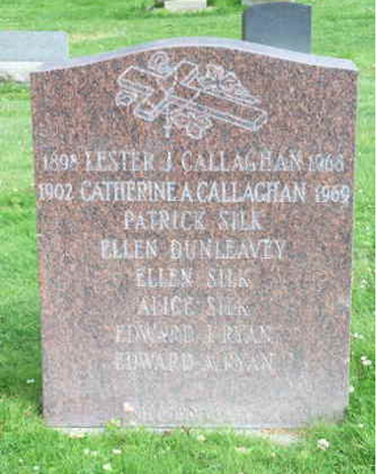

Burial: Holy Cross Cemetery, Colma CA (F19-5)

Occupation: Cable Car Gripman, Fireman at the ship yards during WWII

Education: Willow Spring School (Birds Landing) and St. Gertrude’s Academy (Rio Vista)

Death: 31 Jul 1968, San Francisco, CA

Burial: Holy Cross Cemetery, Colma CA (F19-5)

Occupation: Cable Car Gripman, Fireman at the ship yards during WWII

Education: Willow Spring School (Birds Landing) and St. Gertrude’s Academy (Rio Vista)

Spouse: Catherine Agnes Silk

Birth: 5 Dec 1902, San Francisco, CA

Death: 16 Jun 1969, San Francisco, CA

Father: Patrick Joseph Silk Mother: Ellen Raftery

Education: St. Agnes’s Academy, San Francisco

Marriage: 16 Sep 1928, San Francisco, CA

Children: Dolores Marie Lorraine Veronica (1930-2010)

Birth: 5 Dec 1902, San Francisco, CA

Death: 16 Jun 1969, San Francisco, CA

Father: Patrick Joseph Silk Mother: Ellen Raftery

Education: St. Agnes’s Academy, San Francisco

Marriage: 16 Sep 1928, San Francisco, CA

Children: Dolores Marie Lorraine Veronica (1930-2010)

Lester Orwood Callaghan was born on May 9, 1898, to John Callaghan and Ellen Millerick. He was their fourth child, but two of his older siblings had died young. He grew up as the only son. He was named after a character in a book that his mother was reading. As neither Lester nor Orwood was a saint’s name, he was baptized Lester Joseph, which he used later in life. Like his daughter, Les hated his name and did not want his grandsons named after him.

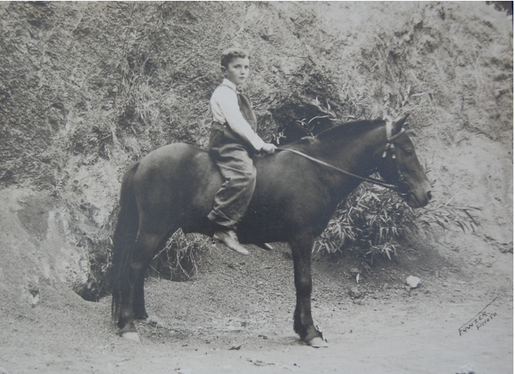

Les’s grandson David Quattrin said Les loved to tell stories of the 1906 Earthquake, riding a horse down Main Street in Rio Vista, and bittersweet memories of his time on the ranch as a child. At age four, he had his picture taken on a pony and, according to a letter from his mother to his sister Ruth, talked of nothing else for months. Later he remembered getting in trouble for lathering his horse Birdie by racing up Kerbie Hill with his cousin Melvin.

In her doctoral dissertation Settling the sunset land: California and its family farmers, (2006) Alexandra Kindell, PhD, uses the John Steinbeck stories in The Red Pony to describe life on a California farm in the late 1880s and early 1900s.

In each of the “Red Pony” stories, Steinbeck focused on one event to make a series of discrete points about rural California and indirectly documented the diurnal patterns of life and work of the Tiflins and their hired hand. In doing this, Steinbeck interwove the gendered divisions of labor on the ranch into his narrative as skillfully as any rural historian. Ruth Tiflin quietly cooked eggs and ham, mended socks, and made cottage cheese. As she spooned clabbered milk into a bag to hang over her sink, she watched the world of men through her window. Her husband, his hired hand, and the Tiflin boy milked the cows, slaughtered pigs, and raked hay. Jody Tiflin went about his daily chores helping his mother in the beginning, feeding chickens and filling the wood box. As he got older, he spent less time helping her, and he spent his free hours away from school with his father and the hired man. Steinbeck defined each character by the nature of his or her work, and as a boy in his early teens, Jody’s rite of passage showed his growth by transitioning from the house to the fields. These are all the same chores that men, women, and children performed in California in 1854, 1884, and even 1924. What might seem banal to modern readers was, in fact, necessary to survival in rural California.

Lester’s experience growing up on the farm would have been similar to that of his father’s. He would have done house chores like collecting eggs, feeding the chickens, milking the cows, and gathering firewood, all under the watchful eye of his mother. He would have begun to shepherd the sheep and maybe help with shearing by the time he was eight. But because of family dynamics, he never got to the fieldhand stage.

Though he never became a full-fledged farmer, Les definitely learned to appreciate growing things. His grandfather had a beautiful rose garden at the house on the Lower Ranch. He and his sisters loved the feel and smell. When he finally was able to own a yard of his own, he planted roses and spent all his spare time caring for them.

Les was one of 12 Callaghan grandchildren, so there were children his age on the Ranch. But three of them died young, including his brother Francis and sister Gertrude. Melvin was the only other boy until Bill came along in 1912. There were 23 Millerick cousins in San Francisco, and he would visit the City or some of them might come up for part of the summer. Since his mother was closest with her sisters Mayme Comisky and Annie Fredricks, Les was close to those cousins. They were also closer to his age than some of the others.

At 5:13 am on April 18,1906, the Earthquake, measuring 8.0 on the Richter scale, stuck San Francisco. The tremors were felt as far away as Sitka, Alaska, Cleveland, Ohio, and Puerto Rico. The ensuing series of Fires did far more damage than the ‘Quake. The Callaghans would have already been up, probably working in the fields. Much less damage was done in Solano County than in The City. According to the Report of the State Earthquake Investigation Committee (1907) found at https://oac.cdlib.org/view?docId=hb1h4n989f&brand=eqf&doc.view=ent,

Rio Vista, Solano County. Population 682. (J. C. Stanton, C.E.) — The character and effects of the shock are described in a note published in the Climatological Report of the U. S. Weather Bureau for April, 1907, as follows:

The shake was very severe. It commenced with a number of quite long vibrations from northwest to southeast and wound up with the figure 8 motion which often accompanies seismic disturbances. It was quite difficult for persons to maintain their footing; but strange to say, nothing was thrown down or overturned, which may be attributed to the gyrating motion. The duration was about 30 seconds, and I am convinced that had it continued 30 seconds longer hardly a house would have been left standing in town. Some lumber piles were thrown down in a lumber yard situated upon a pile wharf, where the disturbance seemed worse than anywhere else; and the water-tower, 60 feet in height, consisting of 2 large tanks containing 100,000 gallons, was seen to sway violently.

Les would later tell his grandsons that Main Street had a lot of damage.

Collinsville, being right on the water and with much of the town on stilts, did not fair quite as well.

Collinsville, Solano County. Population 300. (Joseph Antonini.) — Collinsville is on the peat of the tule land, with hard clay 2 feet below the surface. The largest building in town, a hotel built on piles, was totally wrecked. Chimneys and water-tanks were over-thrown. The movement was east.

One can just picture the hotel bouncing off the stilts and ending up as a pile of kindling in the River.

The Millerick cousins were fairly safe from the Earthquake and Fire. They were living in Bernal Heights, where the ground was solid and the neighborhood was well beyond the southern extent of the fires. Les and his mother went to visit a few weeks later, and he remembered riding the streetcar through an eerily quiet and empty downtown. The South of Market area where his grandparents had first settled was burned to the ground. Some of the cousins moved up to Sonoma because they felt safer. Uncle John Millerick moved his family but stayed in town because, as a carpenter, there was a lot of work available.

On May 9, 1908—Les’s tenth birthday—his mother died. She had been sick for some weeks, but no child expects a parent’s death. Les had always been very close to his mother and loved her dearly. He was grief-stricken. His relationship with his father, which had never been particularly solid, began to worsen. As John handled his grief by becoming more isolated (and drinking more), Aunt Nora stepped in to help raise the Les and his sisters. It was most likely Nora who enrolled Les in St. Joseph’s Academy.

St. Joseph’s Academy in Rio Vista was an offshoot of St. Gertrude’s Academy. St. Gertrude’s was an all-girls boarding school founded in1876 by Gertrude and Joseph Bruning. Mr. Bruning was a large landholder and successful businessman who is considered to be one of the founders of the town. He and his wife were interested in furthering education in the area and established the 35-acre school for $20,000. According to the school handbook, courses included everything a young woman could need at the turn of the century: penmanship, drawing, singing, and elocution. In later years, students learned such things as spelling, oral arithmetic, oral geography, and grammar. All of this for the grand sum of $112.50 per each five-month term. Additional lessons in music could be picked up for $30 a term and singing, painting, or drawing for another $20. It was more expensive than John would have been willing to pay.

Nora had gone to St. Gertrude’s, as had Les’s sister Ruth and several other Callaghan children. May Callaghan was named after Sr. Mary Camillus, Mother-Superior of the Mercy nuns that ran the school. In 1902, the sister of one of the teachers died, and her three young sons came to live with their aunt in the Bruning home. Word spread among the school’s parents that the boys were being taught, and they wanted their sons educated as well. St. Joseph’s (later St. Joseph’s Military) Academy, “a school wherein Christian influences prevail, and where development of character is placed above all considerations,” was founded. After the school closed in 1932, Nora bought the property, and, later, the family sold it to the Rio Vista School District to build Riverview Middle School and installed a baseball diamond.

In 1911, Les received the sacrament of confirmation. His grandfather Michael serving was his sponsor. For his confirmation name he chose Francis, after his deceased older brother.

In 1912, Les’s uncle Bill had a son, whom he also named Bill. Despite their age difference, Young Bill, as he came to be known, and Les were very close. Les considered Bill to be the little brother he never had. They shared a strong common interest in sports, an interest their cousin Mel did not seem to share. They also shared a common strong faith.

Les graduated from St. Joseph’s in 1913. He wanted to go to St. Mary’s like his father and uncles, but his father said no. Tensions between Les and his father rose even more when John began to date Frances Driscoll. Les considered it a betrayal of his mother’s memory. According to Les, he was thrown out of the house and was sent to “the orphanage” where he remembered picking hops in Ukiah. It is unknown which “orphanage” he was in, but it might have been the Albertinum in Ukiah, which was a combination orphanage and boarding school. Or it might have been the Good Templar Orphanage in Vallejo. His name is not listed on the extent rolls of either institution, though. At the orphanage, he met his life-long friends Frank Murphy and Clarence “Brick” Doyle. He left the orphanage when he turned 18. While he was there, in 1914, his father married Frances.

Les was one of 12 Callaghan grandchildren, so there were children his age on the Ranch. But three of them died young, including his brother Francis and sister Gertrude. Melvin was the only other boy until Bill came along in 1912. There were 23 Millerick cousins in San Francisco, and he would visit the City or some of them might come up for part of the summer. Since his mother was closest with her sisters Mayme Comisky and Annie Fredricks, Les was close to those cousins. They were also closer to his age than some of the others.

At 5:13 am on April 18,1906, the Earthquake, measuring 8.0 on the Richter scale, stuck San Francisco. The tremors were felt as far away as Sitka, Alaska, Cleveland, Ohio, and Puerto Rico. The ensuing series of Fires did far more damage than the ‘Quake. The Callaghans would have already been up, probably working in the fields. Much less damage was done in Solano County than in The City. According to the Report of the State Earthquake Investigation Committee (1907) found at https://oac.cdlib.org/view?docId=hb1h4n989f&brand=eqf&doc.view=ent,

Rio Vista, Solano County. Population 682. (J. C. Stanton, C.E.) — The character and effects of the shock are described in a note published in the Climatological Report of the U. S. Weather Bureau for April, 1907, as follows:

The shake was very severe. It commenced with a number of quite long vibrations from northwest to southeast and wound up with the figure 8 motion which often accompanies seismic disturbances. It was quite difficult for persons to maintain their footing; but strange to say, nothing was thrown down or overturned, which may be attributed to the gyrating motion. The duration was about 30 seconds, and I am convinced that had it continued 30 seconds longer hardly a house would have been left standing in town. Some lumber piles were thrown down in a lumber yard situated upon a pile wharf, where the disturbance seemed worse than anywhere else; and the water-tower, 60 feet in height, consisting of 2 large tanks containing 100,000 gallons, was seen to sway violently.

Les would later tell his grandsons that Main Street had a lot of damage.

Collinsville, being right on the water and with much of the town on stilts, did not fair quite as well.

Collinsville, Solano County. Population 300. (Joseph Antonini.) — Collinsville is on the peat of the tule land, with hard clay 2 feet below the surface. The largest building in town, a hotel built on piles, was totally wrecked. Chimneys and water-tanks were over-thrown. The movement was east.

One can just picture the hotel bouncing off the stilts and ending up as a pile of kindling in the River.

The Millerick cousins were fairly safe from the Earthquake and Fire. They were living in Bernal Heights, where the ground was solid and the neighborhood was well beyond the southern extent of the fires. Les and his mother went to visit a few weeks later, and he remembered riding the streetcar through an eerily quiet and empty downtown. The South of Market area where his grandparents had first settled was burned to the ground. Some of the cousins moved up to Sonoma because they felt safer. Uncle John Millerick moved his family but stayed in town because, as a carpenter, there was a lot of work available.

On May 9, 1908—Les’s tenth birthday—his mother died. She had been sick for some weeks, but no child expects a parent’s death. Les had always been very close to his mother and loved her dearly. He was grief-stricken. His relationship with his father, which had never been particularly solid, began to worsen. As John handled his grief by becoming more isolated (and drinking more), Aunt Nora stepped in to help raise the Les and his sisters. It was most likely Nora who enrolled Les in St. Joseph’s Academy.

St. Joseph’s Academy in Rio Vista was an offshoot of St. Gertrude’s Academy. St. Gertrude’s was an all-girls boarding school founded in1876 by Gertrude and Joseph Bruning. Mr. Bruning was a large landholder and successful businessman who is considered to be one of the founders of the town. He and his wife were interested in furthering education in the area and established the 35-acre school for $20,000. According to the school handbook, courses included everything a young woman could need at the turn of the century: penmanship, drawing, singing, and elocution. In later years, students learned such things as spelling, oral arithmetic, oral geography, and grammar. All of this for the grand sum of $112.50 per each five-month term. Additional lessons in music could be picked up for $30 a term and singing, painting, or drawing for another $20. It was more expensive than John would have been willing to pay.

Nora had gone to St. Gertrude’s, as had Les’s sister Ruth and several other Callaghan children. May Callaghan was named after Sr. Mary Camillus, Mother-Superior of the Mercy nuns that ran the school. In 1902, the sister of one of the teachers died, and her three young sons came to live with their aunt in the Bruning home. Word spread among the school’s parents that the boys were being taught, and they wanted their sons educated as well. St. Joseph’s (later St. Joseph’s Military) Academy, “a school wherein Christian influences prevail, and where development of character is placed above all considerations,” was founded. After the school closed in 1932, Nora bought the property, and, later, the family sold it to the Rio Vista School District to build Riverview Middle School and installed a baseball diamond.

In 1911, Les received the sacrament of confirmation. His grandfather Michael serving was his sponsor. For his confirmation name he chose Francis, after his deceased older brother.

In 1912, Les’s uncle Bill had a son, whom he also named Bill. Despite their age difference, Young Bill, as he came to be known, and Les were very close. Les considered Bill to be the little brother he never had. They shared a strong common interest in sports, an interest their cousin Mel did not seem to share. They also shared a common strong faith.

Les graduated from St. Joseph’s in 1913. He wanted to go to St. Mary’s like his father and uncles, but his father said no. Tensions between Les and his father rose even more when John began to date Frances Driscoll. Les considered it a betrayal of his mother’s memory. According to Les, he was thrown out of the house and was sent to “the orphanage” where he remembered picking hops in Ukiah. It is unknown which “orphanage” he was in, but it might have been the Albertinum in Ukiah, which was a combination orphanage and boarding school. Or it might have been the Good Templar Orphanage in Vallejo. His name is not listed on the extent rolls of either institution, though. At the orphanage, he met his life-long friends Frank Murphy and Clarence “Brick” Doyle. He left the orphanage when he turned 18. While he was there, in 1914, his father married Frances.

Les had grown into a thick-set farm boy—5’9” and 180 lbs., with blue eyes and brown hair. Back in Rio Vista, Les moved in with his Aunt Nora, instead of going back to the ranch. He played baseball like his father and uncles had, but he played for the Rio Vistans, archrivals of his father’s Birds Landing team. He was known as a “strong right fielder with a good bat.” He had hopes of getting a rookie contract with the Brooklyn Dodgers, but it never came through. He kept his wool uniform among the other treasures in his cedar chest in the basement of his Capistrano Street house, where he would occasionally take it out to show his grandsons. Dolores later donated it to the Rio Vista Museum. Two years after Less’ death, his grandson Kevin played right field and was also known for his batting.

In 1917, Les moved to San Francisco, and made the transition from rural life to city life which many of his generation had to make. He went to work for his uncle William Millerick as an apprentice printer. Uncle Will was a printer/ compositor/ typesetter who owned his own bookbinding company. Les’s sisters both moved to the City about the same time. In October 1918, he received his selective service notice. With the Great War ending, though, he was mustered in and right back out on November 11, 1918.

Prohibition did not bother Les much, as he was not a heavy drinker. He enjoyed the early 1920s as a bachelor about town with his friends Brick and Murph. He loved football, especially Notre Dame, with his hero Knute Rockne. He was a St. Mary’s football fan as well and often went to the Little-Big Game (St. Mary’s vs. Santa Clara, as opposed to the Big Game, Cal vs. Stanford) with his cousin Bill, who had attended Santa Clara. Needless to say, he was also a Giants a fan after the Dodgers turned him down and love grew when they moved to San Francisco in 1962. Dave remembered him pruning his roses with the game always on in the background.

Les’s sister Ruth worked for the phone company and invited him to a dance they were sponsoring. He and Brick decided to go. There, Les saw Catherine Silk for the first time. When Brick dared him to “go over and make that big blonde smile,” he approached Catherine, and she ultimately did smile.

In 1917, Les moved to San Francisco, and made the transition from rural life to city life which many of his generation had to make. He went to work for his uncle William Millerick as an apprentice printer. Uncle Will was a printer/ compositor/ typesetter who owned his own bookbinding company. Les’s sisters both moved to the City about the same time. In October 1918, he received his selective service notice. With the Great War ending, though, he was mustered in and right back out on November 11, 1918.

Prohibition did not bother Les much, as he was not a heavy drinker. He enjoyed the early 1920s as a bachelor about town with his friends Brick and Murph. He loved football, especially Notre Dame, with his hero Knute Rockne. He was a St. Mary’s football fan as well and often went to the Little-Big Game (St. Mary’s vs. Santa Clara, as opposed to the Big Game, Cal vs. Stanford) with his cousin Bill, who had attended Santa Clara. Needless to say, he was also a Giants a fan after the Dodgers turned him down and love grew when they moved to San Francisco in 1962. Dave remembered him pruning his roses with the game always on in the background.

Les’s sister Ruth worked for the phone company and invited him to a dance they were sponsoring. He and Brick decided to go. There, Les saw Catherine Silk for the first time. When Brick dared him to “go over and make that big blonde smile,” he approached Catherine, and she ultimately did smile.

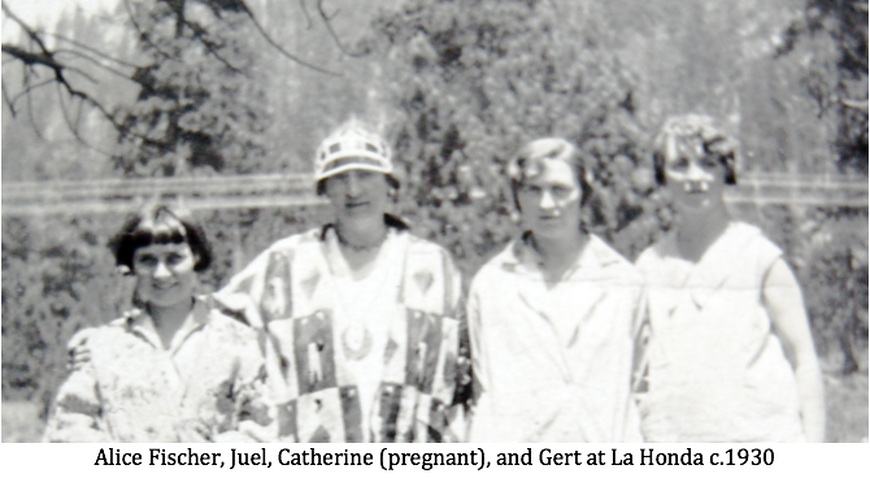

Catherine Agnes Silk was born on December 5, 1902. She was the youngest of the seven children of Patrick Silk and Ellen Raftery, both of Galway. Only two sisters and one brother had survived childhood. Catherine was named after her youngest aunt Kate Silk and her oldest aunt Mary Agnes Silk, but her sisters called her Catty or Kay. She had been baptized in early 1903 at St. Patrick’s Church, but the records were lost in the Fire, so the exact date and the names of her godparents are unknown.

Her father died of pneumonia when she was just six months old. She moved around the City as a child, as her mother Ellen tried to cope with the death of her first and then her second husband. In 1910, Catherine was seven when Ellen died of valvular heart disease, and the family was split up. Catherine was taken in and raised by her Uncle Jim Silk and Aunt Mary (nee Moran) in St. Agnes Parish. She always wanted to be closer to her sisters (who were very close to one another), and Catherine always felt hurt by the fact that Juel had taken Gert in, but not her. It is unknown exactly when Gert moved in with Juel, but she may have already been a teenager at the time. Being younger than Gert by 3 years, the adults probably thought Catherine needed more attention. Why Jim and Mary only took Catherine and not Gert is unknown. Already an introvert, though, this situation added to Catherine’s sense of isolation.

Jim and Mary owned the houses at 720-722 and 717 Clayton Street in the Haight District. Catherine would live there with them until she married. Aunt Mary’s brother lived in 724 Clayton and Catherine grew up with her Moran cousins Adelaide, Marie, and Willie. Though her sisters called her "Catty," the Morans called her Piano Legs. Unlike her aunt and namesake, she never went by Kate or Katie. Catherine was a tomboy who used to go "skitchin'" on the trolley cars, which meant she would grab the back of the car while wearing roller skate to hitch a ride. According to Dolores, she played the piano beautifully but hated it because her aunt had always forced her to get up early before school to practice. After she married, she never had a piano in the house. Years later she remembered that Cousin Willie would sit next to her while she played and “have a feel” on her thigh. Dolores was mortified by the story, but Catherine would just laugh and say, “He’s a priest now. I wonder if he remembers that.” Willie was Fr. Bill Moran who, after a long career as a chaplain in the US Army, was appointed Auxiliary Bishop to the Army by Cardinal Spellman.

Catherine was a devout Catholic. She attended St. Agnes’ Grammar School and she was confirmed at St. Agnes Church on October 25, 1914. Her sponsor was the 7th Grade teacher, Mrs. Delahienty, who sponsored the whole class. Catherine continued at St. Agnes’ Presentation Academy for Young Ladies (later known as Presentation High School). Her high school experiences included lectures in Sacred Heart Hall every Friday during Lent. According a memoir written by a graduating senior in 1918, the lectures were “on our Lord’s Passion. How we did look forward to and enjoy these instructions. On April 23, the Feast of Our Lady of Good Council, we were initiated into the [next] degree of the School Sodality. That also was a memorable day in my life.” School unity was accentuated by an annual school picnic in honor of the graduating class and a “Candy Party” for the younger children in the grammar school.

Her father died of pneumonia when she was just six months old. She moved around the City as a child, as her mother Ellen tried to cope with the death of her first and then her second husband. In 1910, Catherine was seven when Ellen died of valvular heart disease, and the family was split up. Catherine was taken in and raised by her Uncle Jim Silk and Aunt Mary (nee Moran) in St. Agnes Parish. She always wanted to be closer to her sisters (who were very close to one another), and Catherine always felt hurt by the fact that Juel had taken Gert in, but not her. It is unknown exactly when Gert moved in with Juel, but she may have already been a teenager at the time. Being younger than Gert by 3 years, the adults probably thought Catherine needed more attention. Why Jim and Mary only took Catherine and not Gert is unknown. Already an introvert, though, this situation added to Catherine’s sense of isolation.

Jim and Mary owned the houses at 720-722 and 717 Clayton Street in the Haight District. Catherine would live there with them until she married. Aunt Mary’s brother lived in 724 Clayton and Catherine grew up with her Moran cousins Adelaide, Marie, and Willie. Though her sisters called her "Catty," the Morans called her Piano Legs. Unlike her aunt and namesake, she never went by Kate or Katie. Catherine was a tomboy who used to go "skitchin'" on the trolley cars, which meant she would grab the back of the car while wearing roller skate to hitch a ride. According to Dolores, she played the piano beautifully but hated it because her aunt had always forced her to get up early before school to practice. After she married, she never had a piano in the house. Years later she remembered that Cousin Willie would sit next to her while she played and “have a feel” on her thigh. Dolores was mortified by the story, but Catherine would just laugh and say, “He’s a priest now. I wonder if he remembers that.” Willie was Fr. Bill Moran who, after a long career as a chaplain in the US Army, was appointed Auxiliary Bishop to the Army by Cardinal Spellman.

Catherine was a devout Catholic. She attended St. Agnes’ Grammar School and she was confirmed at St. Agnes Church on October 25, 1914. Her sponsor was the 7th Grade teacher, Mrs. Delahienty, who sponsored the whole class. Catherine continued at St. Agnes’ Presentation Academy for Young Ladies (later known as Presentation High School). Her high school experiences included lectures in Sacred Heart Hall every Friday during Lent. According a memoir written by a graduating senior in 1918, the lectures were “on our Lord’s Passion. How we did look forward to and enjoy these instructions. On April 23, the Feast of Our Lady of Good Council, we were initiated into the [next] degree of the School Sodality. That also was a memorable day in my life.” School unity was accentuated by an annual school picnic in honor of the graduating class and a “Candy Party” for the younger children in the grammar school.

St. Agnes Academy also provided an excellent education. The classes were small, only a dozen or so students per graduating class. In 1915, the school moved from its location at 755 Ashbury where it had started in 1907 to the building at 255 Masonic which would serve as its home until closing in 1988. The curriculum included Latin and Spanish, Algebra and Geometry, Ancient and Modern History, English, bookkeeping, typing and short-hand. In 1921, she graduated from the Commercial Institute of St. Agnes Academy. She received national certifications in Palmer Method business writing and in typewriting, the latter awarded by the Underwood Typewriting Company for “speed and accuracy in typewriting 40 words per minute according to the International Contest Rules for ten minutes.” Her piano skills helped her with machines like the typewriter and adding machine. Entering the work force, Catherine obtained a job as a stenographer at Pacific Telephone and Telegraph (PT&T).

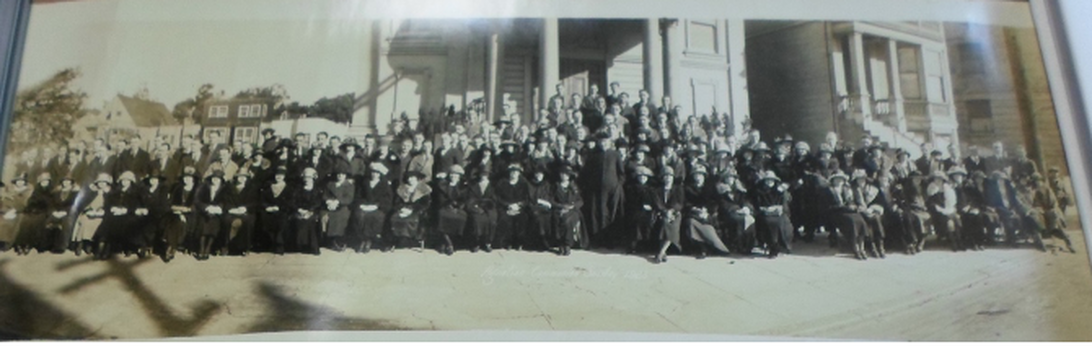

After graduation, Catherine continued her engagement with St. Agnes. She joined the Agnetian Auxiliary of the Agnetian Club. The club had started in 1919 and was confined to young adults over 18. It had an equal number of men and women. The membership grew to 2,000. It was a social club with sports and dramatics, socials, and monthly communions. Catherine is the seventh from the left, front row, in the 1923 Agnetian Communion photo above. The famous San Francisco lawyer Vincent Hallinan was also a member. Their football, basketball and baseball teams competed with some local colleges and did very well. In 1925, Fr. Butler, the pastor who had started the club, was moved to another parish and the society lost steam. Later, she would attend retreats with women from St. Brigid’s parish.

Like many San Francisco middle class families, the Silks and Morans spent summers in cabins on the Russian River. They would hike, swim in the river, and play cards. Catherine grew to enjoy Whist, Pinnacle, and Gin Rummy, the latter of which she taught her grandsons. A 1921 Chronicle article stated, “Arrangements are underway to make the whist [tournament] and dansant (small dance) for the benefit of the churches of the summering places of Guerneville, Monte Rio, and Rio Nido the big pre-Lenten social event.” The article named Catherine and her brother John among those interested in the success of the affair. The affair would take place on February 3, 1921, in the Colonial Ball Room of the St. Francis Hotel.

Like many San Francisco middle class families, the Silks and Morans spent summers in cabins on the Russian River. They would hike, swim in the river, and play cards. Catherine grew to enjoy Whist, Pinnacle, and Gin Rummy, the latter of which she taught her grandsons. A 1921 Chronicle article stated, “Arrangements are underway to make the whist [tournament] and dansant (small dance) for the benefit of the churches of the summering places of Guerneville, Monte Rio, and Rio Nido the big pre-Lenten social event.” The article named Catherine and her brother John among those interested in the success of the affair. The affair would take place on February 3, 1921, in the Colonial Ball Room of the St. Francis Hotel.

Les and Catherine met sometime in the mid-1920s. They were drawn together by their shared loss of parents, heightened in part by their mothers’ sharing of the name Ellen. They married on September 16, 1928, at St. Agnes Church. The best man was Brick Doyle and the maid of honor was Catherine’s best friend Madeline Bennett.

Catherine moved into Les’s apartment at 1174 Sacramento Street, on the east slope of Nob Hill. Shortly after they married, Les lost his job when the print shop closed. Luckily, he was not out of work for long. He had worked as a streetcar conductor in 1920 and had some friends still in the business who helped him get a job as a gripman. Years later, Catherine would tell the story that she had gone to St. Brigid’s Church and prayed before the statue of Our Lady of Dolors for him to get a job and that she promised to name their daughter Dolores if her prayers were answered. They were and she did. Her memory must have been off, though, because Les got the job almost a year before Catherine became pregnant.

Among Catherine and Les’s best friends were Mabel and Augie Muller. Augie was a taxi driver and chauffer (later a truck driver) who had worked in the 1920s with Lester’s brother-in-law Arnold “Trigger” O’Larte. They would have cocktail hour together (“Vodka tonics, all around!”) and played cards weekly. They spent summers together at the River.

Catherine moved into Les’s apartment at 1174 Sacramento Street, on the east slope of Nob Hill. Shortly after they married, Les lost his job when the print shop closed. Luckily, he was not out of work for long. He had worked as a streetcar conductor in 1920 and had some friends still in the business who helped him get a job as a gripman. Years later, Catherine would tell the story that she had gone to St. Brigid’s Church and prayed before the statue of Our Lady of Dolors for him to get a job and that she promised to name their daughter Dolores if her prayers were answered. They were and she did. Her memory must have been off, though, because Les got the job almost a year before Catherine became pregnant.

Among Catherine and Les’s best friends were Mabel and Augie Muller. Augie was a taxi driver and chauffer (later a truck driver) who had worked in the 1920s with Lester’s brother-in-law Arnold “Trigger” O’Larte. They would have cocktail hour together (“Vodka tonics, all around!”) and played cards weekly. They spent summers together at the River.

In early 1930, they moved to 1446 Jackson Street, near Hyde, in St. Brigid’s Parish. On October 1, 1930, their only daughter Dolores was born at St. Mary’s Hospital. Another baby was born on the same day in the same hospital room, to an unwed mother who refused to look at or hold him. When Mabel and Augie visited Catherine, they were touched and adopted the boy, naming him Bob. Dolores and Bob were raised like siblings. That would be the closest Dolores would have to a sibling. After the birth, Catherine and Les were informed that Catherine had a “tipped uterus” which would cause difficulty with getting pregnant in the future and that it would require surgery to resolve. Given the financial situation of the time and the risks of the surgery, they chose not to fix the problem, and dolores remained their only child.

Two years later, they moved into Mayme Millerick Comisky’s big apartment building at 301 Hugo Street on the corner of 4th Avenue, near Kezar Stadium, where they were back in St. Agnes Parish only a few blocks from Uncle Jim’s house. Mayme was Les’s aunt on his mother’s side, and her building was where many of the Millerick cousins (especially the newlyweds) lived during the Depression so they could get their feet back under them financially. Thus, it became known as The Newlywed Apartments.

Two years later, they moved into Mayme Millerick Comisky’s big apartment building at 301 Hugo Street on the corner of 4th Avenue, near Kezar Stadium, where they were back in St. Agnes Parish only a few blocks from Uncle Jim’s house. Mayme was Les’s aunt on his mother’s side, and her building was where many of the Millerick cousins (especially the newlyweds) lived during the Depression so they could get their feet back under them financially. Thus, it became known as The Newlywed Apartments.

In 1935, they moved back to St. Brigid’s Parish to the place Dolores always considered her home—1229 Vallejo Street. Catherine had friends in the neighborhood, including Helen DePalma—the Italian woman who lived upstairs. Helen taught her to make spaghetti gravy that became a family tradition at all holiday dinners. (Kevin still uses the recipe.) The neighborhood had two theatres and the family would go to the movies twice a week, Dolores often riding on Les’s shoulders. They also liked St. Brigid’s community and looked forward to Dolores attending that school the following fall. Also, her uncle Jim had died the year before and Catherine felt less of a tie to the St. Agnes neighborhood.

Summers were spent visiting the ranch in Rio Vista, at the Fischer’s horse ranch in La Honda, or at the Russian River. Dolores remembered that the three of them did everything together. The only time as a child that she spent the night with someone else was when Catherine and Les went out of town for a Gripmans’ Convention in Seattle. She stayed with her Aunt Juel and Uncle Charlie Fischer.

Summers were spent visiting the ranch in Rio Vista, at the Fischer’s horse ranch in La Honda, or at the Russian River. Dolores remembered that the three of them did everything together. The only time as a child that she spent the night with someone else was when Catherine and Les went out of town for a Gripmans’ Convention in Seattle. She stayed with her Aunt Juel and Uncle Charlie Fischer.

Catherine liked to dressing up to go out, whether it was to dinner, or downtown to shop (which was a formal occasion in those days), or to the 1939 World’s Faire on Treasure Island. She loved her wool coat with the fur-lined collar and was jealous when Les bought Dolores a Mouton coat for her graduation. She also liked to where Channel No 5. Years after when Dolores was shopping at Macy’s with her daughter-in-law Kelly and granddaughter Ceri, Kelly wafted some Channel No 5 to see if she liked it. Kelly said, “She stood stock still and almost cried, saying ‘My mother must have used that, because it makes me think of her!’”

On February 5, 1941, Les’s father John died. Les, Catherine, and Dolores took the bus to Rio Vista for the funeral. His older sister Ruth, though not healthy, insisted on going as well and the stress affected her. On February 18, Ruth died of a sudden heart attack at the age of 49. Les was far more strongly hit by losing Ruth than losing his father.

Les and his sisters had inherited those 310 acres from their grandfather Michael at his death in 1920, but they could not do anything with the land because their father had a lifetime right to live on and work the Ranch. With John’s death—and a strong push from Madelyn and Ruth’s widower George—Les agreed to sell the Ranch to their Aunt Louise’s nephew, Neal Anderson, Jr. Les had grown up with Neal, who owned part of his father’s nearby acreage. Les did not really want to let go of the land, but everyone needed the money, and he knew Catherine would never agree to leave the City and enter the rural life. “It was just too damned hot up there!”

The sale did mean turning out their step-mother. She tried to sue, thinking she had a claim to the farm, but, since John had never owned it, she had no claim. George Robinson took his share and left town (“Good riddance to bad rubbish,” Catherine would say), Madelyn bought her daughter Geri a car, and Les put the money in the bank until his daughter Dolores graduated from high school.

According to Dave, Les was extremely saddened about losing the land, and he always wanted to go back to visit. But think he didn't go back because “it would have broken his heart over what was once, and now, not at all.”

As Les entered his 40s, his body began to break down from all the hard work. In 1940, he had to take time off because of a hernia he had gotten from the work. In 1942, he was drafted but was rated 4-H (“registrant exempted because of hardship to dependents”). He took leave from MUNI to serve as a firefighter in the Naval dry docks at Hunters Point. Augie had convinced him it would be easier on him physically than his job as a gripman, but he hated being in the holds of the ships. In June of 1944, he underwent surgery for a second hernia, as well as for varicose veins in his right leg. He had developed phlebitis from his many years of stepping on the cable car brake. That December, he was released from service to the Navy and went back to MUNI, but now as a janitor.

On February 5, 1941, Les’s father John died. Les, Catherine, and Dolores took the bus to Rio Vista for the funeral. His older sister Ruth, though not healthy, insisted on going as well and the stress affected her. On February 18, Ruth died of a sudden heart attack at the age of 49. Les was far more strongly hit by losing Ruth than losing his father.

Les and his sisters had inherited those 310 acres from their grandfather Michael at his death in 1920, but they could not do anything with the land because their father had a lifetime right to live on and work the Ranch. With John’s death—and a strong push from Madelyn and Ruth’s widower George—Les agreed to sell the Ranch to their Aunt Louise’s nephew, Neal Anderson, Jr. Les had grown up with Neal, who owned part of his father’s nearby acreage. Les did not really want to let go of the land, but everyone needed the money, and he knew Catherine would never agree to leave the City and enter the rural life. “It was just too damned hot up there!”

The sale did mean turning out their step-mother. She tried to sue, thinking she had a claim to the farm, but, since John had never owned it, she had no claim. George Robinson took his share and left town (“Good riddance to bad rubbish,” Catherine would say), Madelyn bought her daughter Geri a car, and Les put the money in the bank until his daughter Dolores graduated from high school.

According to Dave, Les was extremely saddened about losing the land, and he always wanted to go back to visit. But think he didn't go back because “it would have broken his heart over what was once, and now, not at all.”

As Les entered his 40s, his body began to break down from all the hard work. In 1940, he had to take time off because of a hernia he had gotten from the work. In 1942, he was drafted but was rated 4-H (“registrant exempted because of hardship to dependents”). He took leave from MUNI to serve as a firefighter in the Naval dry docks at Hunters Point. Augie had convinced him it would be easier on him physically than his job as a gripman, but he hated being in the holds of the ships. In June of 1944, he underwent surgery for a second hernia, as well as for varicose veins in his right leg. He had developed phlebitis from his many years of stepping on the cable car brake. That December, he was released from service to the Navy and went back to MUNI, but now as a janitor.

After renting for years, Les and Catherine reaching into the bank account where he had put the money from the sale of the Ranch and bought the house at 386 Capistrano, in Corpus Christi Parish. The area was known as Mission Terrace back in 1924 when the house was built, but it is now known as Balboa Park. They stayed on Vallejo Street until Dolores graduated from St. Brigid’s High School. Corpus Christi was near City College where Dolores would be attending school that fall. Les switched his janitor shift to the Car Barn on San Jose and Geneva where he worked sweeping up the brick dust of the building his Millerick uncles had built. As an added bonus, the Mullers lived in the neighborhood.

Moving to a new part of town was easier on Lester than Catherine. Les loved his new house, and he especially liked having a garden to work. Being a member of the Knights of Columbus, he also had an immediate source of new friends. Catherine’s friends, on the other hand, were from the old neighborhood and associated with St. Brigid’s. She missed them and it was hard to make new friends. She did not have an automatic connection with Corpus Christi as Dolores was no longer in a school community that included the mothers. There were several neighbors who would become Catherine’s friends, though, including Mrs. Campi and Mrs. Donovan who lived on either side of the new house and Mrs. Wetland who lived across the back alley.

Catherine did enjoy the domestic life of a homeowner, though she would never admit it. She cleaned daily and spent a great deal of time in the kitchen, either cooking or hanging out the back window talking to the neighbors or to Les as he worked on his roses in the yard. Catherine had many, many mason jars that she used for canning, and Les built 30 feet of cabinets in the basement for her to put up fruits. The best were her peaches, though her pickles were also good. And she made an outstanding rhubarb pie.

Les loved his roses. They reminded him of his own grandfather’s rose garden on the Lower Ranch. Kevin remembered that there was a lawn in at the front half and sand in back where he dug holes with a small hammer that had been his great grandfather’s, and that the roses were around the perimeter. Dave remembered the yard layout much better than Kevin:

...front to back, it was calla lilies (ugh, still hate them—snail condos), then yellow, pink and red...all tea garden (small flowers)...there were four bushes down the right side (Donovan's)...can't remember what they were, but don't think they were roses...a small lawn between the walks with a large section that went up to the back walkway before the fence. He never planted anything there...asked him a couple of times why...he said "I want to keep it the way it was when the Cayuga River was there." At other times when I mentioned extending the lawn, he said "I want to remember the sand dunes when I first visited SF."

That was where Les taught Dave about gardening. Dave raised his own roses in Concord later.

and Grandma sticking her head out the kitchen window saying “Lester, what are you doing?” He would turn to me and say “Well, we've stayed away from her too long....she wants to know what we're doing...so much for peace and quiet.” We'd both chuckle and go inside laughing. “WHAT are you laughing about?” We'd just laugh louder.

Les and Catherine hosted great Thanksgiving and Christmas dinners for the family at the new house. Catherine’s informal china (from occupied Japan) and formal Syracuse china are still in the family, and someday her great granddaughters will use them. To this day, her grandson Kevin still uses the milk-glass serving plates and the crystal bowls for olives and pickles for holiday dinners like she did. It is a family tradition.

Moving to a new part of town was easier on Lester than Catherine. Les loved his new house, and he especially liked having a garden to work. Being a member of the Knights of Columbus, he also had an immediate source of new friends. Catherine’s friends, on the other hand, were from the old neighborhood and associated with St. Brigid’s. She missed them and it was hard to make new friends. She did not have an automatic connection with Corpus Christi as Dolores was no longer in a school community that included the mothers. There were several neighbors who would become Catherine’s friends, though, including Mrs. Campi and Mrs. Donovan who lived on either side of the new house and Mrs. Wetland who lived across the back alley.

Catherine did enjoy the domestic life of a homeowner, though she would never admit it. She cleaned daily and spent a great deal of time in the kitchen, either cooking or hanging out the back window talking to the neighbors or to Les as he worked on his roses in the yard. Catherine had many, many mason jars that she used for canning, and Les built 30 feet of cabinets in the basement for her to put up fruits. The best were her peaches, though her pickles were also good. And she made an outstanding rhubarb pie.

Les loved his roses. They reminded him of his own grandfather’s rose garden on the Lower Ranch. Kevin remembered that there was a lawn in at the front half and sand in back where he dug holes with a small hammer that had been his great grandfather’s, and that the roses were around the perimeter. Dave remembered the yard layout much better than Kevin:

...front to back, it was calla lilies (ugh, still hate them—snail condos), then yellow, pink and red...all tea garden (small flowers)...there were four bushes down the right side (Donovan's)...can't remember what they were, but don't think they were roses...a small lawn between the walks with a large section that went up to the back walkway before the fence. He never planted anything there...asked him a couple of times why...he said "I want to keep it the way it was when the Cayuga River was there." At other times when I mentioned extending the lawn, he said "I want to remember the sand dunes when I first visited SF."

That was where Les taught Dave about gardening. Dave raised his own roses in Concord later.

and Grandma sticking her head out the kitchen window saying “Lester, what are you doing?” He would turn to me and say “Well, we've stayed away from her too long....she wants to know what we're doing...so much for peace and quiet.” We'd both chuckle and go inside laughing. “WHAT are you laughing about?” We'd just laugh louder.

Les and Catherine hosted great Thanksgiving and Christmas dinners for the family at the new house. Catherine’s informal china (from occupied Japan) and formal Syracuse china are still in the family, and someday her great granddaughters will use them. To this day, her grandson Kevin still uses the milk-glass serving plates and the crystal bowls for olives and pickles for holiday dinners like she did. It is a family tradition.

Catherine did like to laugh. She loved to watch Red Skelton and Art Carney. She was particularly fond of Ish Kabibble, a comedian on the Kay Kaiser Komedy Hour. Les never missed the Jackie Gleason Show. He also liked westerns, especially The Virginian. In the early 1950s, Les finally bought a car, much to Catherine’s delight. She never learned to drive, but she loved to take Sunday drives after mass with him. They would go to Holy Cross Cemetery to “visit the family.” Sometimes, they would drive down the Peninsula to enjoy the sun and see the scenery on Highway 35. Sometimes they would picnic at the Pulgas Water Temple. She was very disappointed when Les decided to let his drivers’ license lapse when he got older and feeling less healthy.

The mid-1950s were difficult on Catherine in many ways. In 1953, both her brother John and her sister Gertrude passed away. The next year, her daughter became pregnant and married John Quattrin. The newlyweds briefly lived with Les and Catherine until their first grandchild child, David Michael, was born on November 6, 1954. The house became a little too crowded, and the Quattrins found an apartment a few blocks away. In 1960, a second grandson, Kevin Joseph, was born.

The year after Dave was born, Catherine’s sister Juel died. Catherine felt more alone, and her drinking started to get out of hand. After reaching 25 years in the Muni union, Les decided to retire. Part of the reason for retirement was to help Catherine. At one point, she tried to quit drinking, but she started hallucinating, seeing snakes coming out of the walls. At that point, Dolores stopped having her babysit Dave. Though Catherine seemed to get the drinking under control, she would struggle with it on and off for the rest of her life.

Another big struggle Catherine had was with her weight. At 5’7’, she was a tall woman for the time, and so she was not seen as overweight until later in life. She loved her sweets, especially hard candies. She would snack while cleaning the house. Her favorite was bread and butter with sugar sprinkled on it. She was also known to get up in the middle of the night and fry up leftover spaghetti. By the time she was in her late 50s, Catherine had been diagnosed with diabetes. (Unbeknownst to her, diabetes had led to the death of her great uncle William Molloy back in 1910. He had had to have his leg amputated and died of infection.) She tried cutting back on her snacking and replaced her hard candies with black licorice and diabetic candies—which her grandsons often ate, much to her chagrin. No matter where she tried to hide them (and she was a very accomplished stasher), her grandsons would always find and munch on them, even though neither of them particularly liked the taste. Catherine finally just gave up, returning the candy dish back to the end table on the living room.

Les and Catherine loved being grandparents, especially Les. He would build lego towns and play with blocks with Dave. He would lay on the floor and shoot marbles with Dave and Kevin. The house on Capistrano had hardwood floors with a rug in the middle, so there was a strip of wood floor around the room to use as a track. (The noise drove Catherine crazy!) He loved to regale his grandsons with stories of the old days and take them on excursions around the City, showing them all the important sights and introducing them to “the guys” on the Cable Cars. That job (and gardening) gave him the strong, sand-paper-like hands that his grandson David remembers. Les and Catherine both taught the boys to play cards, though Catherine got mad at Les for getting out the poker chips and teaching them how to gamble. (“it’s more fun if you are betting.”). In 1968, Dolores gave birth to a daughter, Laura Ann. Les did not live to meet Laura, though he would have loved having a granddaughter. One of Kevin’s memories of Catherine was of her sitting on the back patio in the sun, holding Laura, and smiling.

The mid-1950s were difficult on Catherine in many ways. In 1953, both her brother John and her sister Gertrude passed away. The next year, her daughter became pregnant and married John Quattrin. The newlyweds briefly lived with Les and Catherine until their first grandchild child, David Michael, was born on November 6, 1954. The house became a little too crowded, and the Quattrins found an apartment a few blocks away. In 1960, a second grandson, Kevin Joseph, was born.

The year after Dave was born, Catherine’s sister Juel died. Catherine felt more alone, and her drinking started to get out of hand. After reaching 25 years in the Muni union, Les decided to retire. Part of the reason for retirement was to help Catherine. At one point, she tried to quit drinking, but she started hallucinating, seeing snakes coming out of the walls. At that point, Dolores stopped having her babysit Dave. Though Catherine seemed to get the drinking under control, she would struggle with it on and off for the rest of her life.

Another big struggle Catherine had was with her weight. At 5’7’, she was a tall woman for the time, and so she was not seen as overweight until later in life. She loved her sweets, especially hard candies. She would snack while cleaning the house. Her favorite was bread and butter with sugar sprinkled on it. She was also known to get up in the middle of the night and fry up leftover spaghetti. By the time she was in her late 50s, Catherine had been diagnosed with diabetes. (Unbeknownst to her, diabetes had led to the death of her great uncle William Molloy back in 1910. He had had to have his leg amputated and died of infection.) She tried cutting back on her snacking and replaced her hard candies with black licorice and diabetic candies—which her grandsons often ate, much to her chagrin. No matter where she tried to hide them (and she was a very accomplished stasher), her grandsons would always find and munch on them, even though neither of them particularly liked the taste. Catherine finally just gave up, returning the candy dish back to the end table on the living room.

Les and Catherine loved being grandparents, especially Les. He would build lego towns and play with blocks with Dave. He would lay on the floor and shoot marbles with Dave and Kevin. The house on Capistrano had hardwood floors with a rug in the middle, so there was a strip of wood floor around the room to use as a track. (The noise drove Catherine crazy!) He loved to regale his grandsons with stories of the old days and take them on excursions around the City, showing them all the important sights and introducing them to “the guys” on the Cable Cars. That job (and gardening) gave him the strong, sand-paper-like hands that his grandson David remembers. Les and Catherine both taught the boys to play cards, though Catherine got mad at Les for getting out the poker chips and teaching them how to gamble. (“it’s more fun if you are betting.”). In 1968, Dolores gave birth to a daughter, Laura Ann. Les did not live to meet Laura, though he would have loved having a granddaughter. One of Kevin’s memories of Catherine was of her sitting on the back patio in the sun, holding Laura, and smiling.

Les, like Catherine, was a devout Catholic, but he had a stronger private prayer life. He knelt by his bed every night and said the Rosary along with the Catholic Radio Network. He was a member of the Knights of Columbus, serving as president of the Corpus Christi Chapter. One of his favorite stories to tell Dave was about marching down Market Street in the Columbus Day Parade.

In early 1968, the doctors diagnosed Les with a rare form of leukemia. He lost weight as well as his hair due to chemotherapy. The disease spread rapidly, within six months, his suffering mercifully ended. On his deathbed, he told Dolores that he had probably spoiled Catherine, but that she needed taking care of. He died on July 31, 1968, at the age of 70. Catherine did not know what to do without him and would pass away in less than a year. Les had wanted to be buried in Rio Vista with his parents, but Catherine said it was too hot and too far for her to visit. After a rosary and wake at Comisky-Roche Funeral Home (owned by the husband of one of his Millerick cousins), there was a Requiem High Mass at Corpus Christi, and he was buried in the Silk plot at Holy Cross. According to his obituary, he was not only a member of the Knights of Columbus (Mission Council No. 2519), he was also a member of the Holy Name Society of Corpus Christi Church, of the Ancient Order of the Hibernians, and the Amalgamated Transit Union. At his funeral, his Millerick cousins remembered him as the kindest, sweetest man among them. “He had a heart of gold and greeted everyone with a warm, open, and genuine smile.”

In early 1968, the doctors diagnosed Les with a rare form of leukemia. He lost weight as well as his hair due to chemotherapy. The disease spread rapidly, within six months, his suffering mercifully ended. On his deathbed, he told Dolores that he had probably spoiled Catherine, but that she needed taking care of. He died on July 31, 1968, at the age of 70. Catherine did not know what to do without him and would pass away in less than a year. Les had wanted to be buried in Rio Vista with his parents, but Catherine said it was too hot and too far for her to visit. After a rosary and wake at Comisky-Roche Funeral Home (owned by the husband of one of his Millerick cousins), there was a Requiem High Mass at Corpus Christi, and he was buried in the Silk plot at Holy Cross. According to his obituary, he was not only a member of the Knights of Columbus (Mission Council No. 2519), he was also a member of the Holy Name Society of Corpus Christi Church, of the Ancient Order of the Hibernians, and the Amalgamated Transit Union. At his funeral, his Millerick cousins remembered him as the kindest, sweetest man among them. “He had a heart of gold and greeted everyone with a warm, open, and genuine smile.”

After Les got sick, she stopped being careful. Losing her lodestone and protector, she rapidly lost interest in everything. Her diet regimen was first on the list to go. The black licorice was still prominently displayed, but the family knew she returned to her favorite sweets and midnight fried spaghetti. In the winter of 1968, she was diagnosed with breast cancer, necessitating a radical mastectomy. Convalescing in her daughter’s house, she soaked her feet and played with her grandchildren. One day, Dolores noticed that Catherine’s left foot was discolored. Her husband was out of town, she had a newborn baby, and another child with the mumps, but she dropped everything and rushed Catherine to St. Mary’s Hospital. With the diabetes out of control, her left foot had become gangrenous. A succession of surgeries ensued, taking first two toes, then half the foot, followed by the rest of the foot, and finally the lower leg. (They family found out later that the exact same thing had happened to her great uncle William Molloy, who had died from gangrene after having his leg amputated in 1910.) Between the surgeries, she returned to Dolores’ house to recuperate and enjoy her grandchildren. But the damage was done.

When losing half the leg turned out not to be enough to halt the progress of the gangrene, Catherine finally relented to the disease taking its course and opted for no further surgeries. Dolores was distraught, but acquiesced to Catherine’s wishes. Catherine died on June 18, 1969, less than eleven months after Les had died. After a rosary and wake at Comisky-Roche, Requiem High Mass was offered at Corpus Christi, and she was interred in the Silk plot at Holy Cross, with her parents and her beloved Lester.

When losing half the leg turned out not to be enough to halt the progress of the gangrene, Catherine finally relented to the disease taking its course and opted for no further surgeries. Dolores was distraught, but acquiesced to Catherine’s wishes. Catherine died on June 18, 1969, less than eleven months after Les had died. After a rosary and wake at Comisky-Roche, Requiem High Mass was offered at Corpus Christi, and she was interred in the Silk plot at Holy Cross, with her parents and her beloved Lester.

Les was an open, welcoming person with a big smile and a hearty laugh. He was also a solid presence upon which everyone could count. Catherine was a loving, caring person whose gruff exterior inadequately hid it from everyone that knew her best. Her grandsons remembered Catherine as an often gregarious and basically good person who had a sharp sense of humor. Dolores remembered her as woman who had a difficult life, but who loved her husband greatly and who was loved in turn. She lived long enough to hold her baby granddaughter, but she could not stay away any longer from the love of her life. Laura lives in the house on Capistrano and knows that Catherine and Les watch over her daily.