William Callaghan and Mary Condon

No photos available

Birth: Jun 1836, Kilbreedy Minor, Limerick

Death: 17 Feb 1924, Inver Grove, Dakota, Minnesota

Burial: Vermillion Township, Dakota, Minnesota

Spouse: Mary Condon

Birth: 1838, Limerick, Ireland

Death: 24 Oct 1898, Inver Grove, Dakota, Minnesota

Father: Patrick Condon

Mother: Ellen

Marriage: 1861

Children: John Joseph (1862-1862)

Patrick H (1864-1916)

Ellen Elizabeth (1868-1954)

Mary Ann (1868-1962)

Catherine (Kate) (1870-1958)

Nora A (1872-1916)

William Edward (1873-1958)

Margaret (Maggie) (1877-1945)

James Stephen (1877-1971)

William Callaghan was born in June of 1836. The exact day is as not known. He was the first of the eight children of John Callaghan and Nora Carroll. William was born in Kilbreedy Minor, Mount Blakeney, Limerick, on land rented from the Blakeneys and worked by the Callaghans for 100+ years. The farm was half was between Kilmallock, Limerick, and Charleville, Cork. Named after his paternal grandfather, in America William began using a middle initial M, but it was never revealed what middle name he chose. One might assume Michael.

In 1844, when William was eight, his family was evicted. As the oldest son, he would have had a front row view of the following year of threats, arrests, and outright fighting that occurred. At one point, a large number of his Carroll uncles and cousins showed up with pitch forks and threw rocks at the land agent and constables who tried to move the Callaghans. Finally, the family was pushed out of their home. They lived for a short time on a neighbor’s property in a mud hut. Then the Blight struck.

In the Autumn of 1845, a blight appeared unexpectedly among the potatoes. It was a black mold or fungus that caused much of the crop to rot in the fields, marking the beginning of the Great Famine (An Gorta Mor). The unique feature of the potato blight was the speed with which it spread. Eye witnesses said that a crop of potatoes in a field would be perfect in the morning time and by evening would be a rotting mass.

Four successive blighted harvests followed. Connacht and Munster were hit worst, where entire populations of towns had to abandon their homes and take to the road, searching for food. Bodies littered the countryside. Many died trying to eat weeds and any plants they could find, giving rise to a medical condition called “green mouth” from the stains. Many more died of typhus or dysentery. Between 1846 and 1849, over a million people died and another million emigrated, causing a population drop of almost 25 percent on the island. Mass graves appeared everywhere, and churches and towns could not properly update the death records. Nine-year-old William would have seen people dying all around him daily for years.

East Limerick, like East Galway and Roscommon, suffered slightly less than some other areas nearby because the land was more fertile and were planted with grains like wheat, barley, and oats, as well as potatoes. The famine was particularly bad in the west Cork area and in Kerry, but it was also bad in and around Charleville town. 72% of the people living in bothán (sod huts) near Charleville were wiped out by the famine. But not all people suffered during these years as some wealthy Irish Catholic middle-class farmers did very well buying land from tenants whose small holdings had been affected by the blight. With their potato crop failing, they had to sell their plot of land to buy food for their family and/or their passage out of the country. Mount Blakeney was devastated. In 1841, there were 40 houses and 336 people living there. By 1851, only 55 people were left in 15 houses. By 1881, there were only 61 people in seven houses.

The family survived intact, but they had to move onto one acre of land sublet to them by William’s uncle John Carroll, near the holy well behind the old Effin Church yard. GoogleEarth shows the plot as the square surrounded by hedges in the top right. The Holy Well is the circle on the top left. They eked out a living as best they could.

William would have grown up with several Carroll cousins his own age. They all would have done work on the farms, but they would have also attended school—though not in the Hedge Schools. That name would have been anachronistic by his father’s time, and students would not have been taught hiding among the hedges. The more correct term would be “pay schools,” as the teachers would have been paid a nominal fee by the families. Classes would have been taught in a variety of locations—anywhere from a chapel or stone house to a mud hut, a cow barn, or in even in the cemetery. There were over 300 pay schools in Limerick by 1823. The curriculum would have included reading, writing, and arithmetic. Reading and writing would usually be in English, but sometimes in Irish, especially in West Limerick and Kerry. Limerick was known for its math curriculum, where some of the teachers were also surveyors. Latin and religion would be taught before mass on Sundays.

When he turned 18 in 1854, it was decided that William would go to America to seek his fortune and hopefully send money back to the family. Based on DNA matches various branches of the family have had in recent years, there seem to have been Carroll cousins in New York and Illinois. Before he left, though, William probably experienced the American Wake.

According to Encyclopedia.com,

The American wake—sometimes called the live wake, farewell supper, or bottle night—was a unique leave-taking ceremony for emigrants from rural Ireland to the United States. American wakes took place prior to the Great Famine, but most evidence survives from the late 1800s and early 1900s, when the custom prevailed among Catholics, especially in western Ireland where traditional customs remained potent. Usually held on the evening prior to an emigrant's departure, the American wake resembled its ceremonial model, the traditional wake for the dead, and its most common name signified that many Catholic country people still regarded emigration as death's equivalent—a permanent breaking of earthly ties. Usually hosted by the emigrant's parents, the American wake, like a traditional wake, was attended by kinfolk and neighbors, featured the liberal consumption of food and drink, and exhibited a seemingly incongruous mixture of grief and gaiety, expressed in lamentations, prayers, games, singing, and dancing.

Although its format was archaic, the American wake was an adaptation to post famine Ireland's social, cultural, and political exigencies. Because emigration was potentially threatening to communal loyalties and values, the leave-taking ceremony interpreted Irish emigration so as to ensure that the emigrants overseas would remain dutiful to the community left behind. The songs, ballads, and other rituals enacted during the American wakes represented a stylized dialogue between the emigrants and the parents, priests, and nationalist politicians who governed Irish Catholic society. Songs that expressed the latter's perspective often ignored the economic causes of emigration and accused the allegedly “selfish,” “hard-hearted” emigrants of “abandoning” their aged mothers and fathers and, by extension, “holy Ireland” itself. In response, the ballads sung from the emigrants' perspective portrayed them not as eager, ambitious, or alienated from Irish poverty or from parental and clerical repression, but as sorrowing “exiles,” victims of British or landlord oppression, who would be miserably homesick overseas until they returned as promised to their parents' hearths. Such songs also excused the emigrants' departures and expiated their guilt by pledging that they would send their parents money from the United States and would remain loyal to their religion and to the cause of Irish freedom. Arguably, then, the harrowing effects of the American wake on young emigrants, at the moment they were leaving home and hence were psychologically most vulnerable, helped to ensure their unusually high levels of remittances, religious fidelity, and nationalist fervor in the New World.

https://www.encyclopedia.com/international/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/american-wakes

In a brilliant performance by an Irish traditional (sean nós) singer Joe Heaney from County Galway, he explained the tradition this way:

What I’m trying to do tonight, in the space I have, is to give you a bit of everything. And the next thing I’m going to do — maybe some of you heard about it, I don’t know — is called The American Wake. Now it’s nothing to do, directly, it’s nothing to do with America. But long ago, when people were going to America and emigrating, their parents knew they’d never see that particular person in this life again.

And the night before they left, the woman or the man who was leaving — It wasn’t so easy then to come home as it is now. They settled down more or less when they went to America, and they got married, and their parents died, meantime they could never see them. But anyway, the man or the woman who was going away visited all the old people in the village, invited them to have a dance that night in the house. And those that weren’t able to go, they gave them a bottle of something as a remembrance.

And they invited the people — Now I’m talking about a time when there was no musical instruments. And of course, long ago, musical instruments were barred, because some of the clergy reckoned that if you played music you were a druid or something — something pagan about you. So maybe it was a good thing, too. But anyway — there was somebody, always, who lilted a tune, and somebody danced to that tune.

Now, in the old country houses they had what was known as a half-door. And sometimes when somebody was dancing on a concrete kitchen floor, they lifted off the half-door, and danced on top of the half-door. Now two of the tunes they used to play was a reel, My Love She’s in America, and a hornpipe, Off to California. This was during the night; and in the morning, of course, the song — the lament — was sung by always — nearly always — the woman. But this is somebody lilting a tune for somebody dancing. My Love She’s in America went something like this:

After lilting the music for the aforementioned, he went on to sing the lament, A stór mo chroí (Treasure of my Heart):

A stór mo chroí, when you’re far away from the home you’ll soon be leaving

And it’s many a time by night and day your heart will be sorely grieving.

Though the stranger’s land might be rich and fair, and riches and treasure golden

You’ll pine, I know, for the long, long ago and the love that’s never olden.

A stór mo chroí, in the stranger’s land there is plenty of wealth and wearing

Whilst gems adorn the rich and the grand there are faces with hunger tearing.

Though the road is dreary and hard to tread, the lights of their city may blind you

You’ll turn, a stór, to Erin’s shore and the ones you left behind you.

A stór mo chroí, when the evening sun over the mountain and meadow is falling

Won’t you turn away from the throng and listen and maybe you’ll hear me calling.

The voice that you’ll hear will be surely mine of somebody’s speedy returning

A rún, a rún, will you come back soon to the one who will always love you.

https://www.joeheaney.org/en/american-wake-the-and-a-stor-mo-chroi/

This link has an audio recording. It is worth a listen.

The next morning, the immigrant(s), most likely accompanied by relatives and neighbors, would have traveled on foot to Charleville to purchase a train ticket to Queenstown (now Cobh), Cork, to board a ship bound for New York City. It is possible William was the laborer from Ireland named W. Callaghan who was on the passenger list of the ship States Rights which entered New York on October 22, 1853, but that cannot be verified. According to his biography in The History of Dakota County (1910), William came to New York in 1854 and stayed for three months before moving on to St. Louis. He quickly moved northeast across the Mississippi River and settled in Alton, Illinois, where he had family in Fr. Michael Carroll, the parish priest at Sts. Peter and Paul Church. Michael had actually been responsible for building the church in 1843.

William would have grown up with several Carroll cousins his own age. They all would have done work on the farms, but they would have also attended school—though not in the Hedge Schools. That name would have been anachronistic by his father’s time, and students would not have been taught hiding among the hedges. The more correct term would be “pay schools,” as the teachers would have been paid a nominal fee by the families. Classes would have been taught in a variety of locations—anywhere from a chapel or stone house to a mud hut, a cow barn, or in even in the cemetery. There were over 300 pay schools in Limerick by 1823. The curriculum would have included reading, writing, and arithmetic. Reading and writing would usually be in English, but sometimes in Irish, especially in West Limerick and Kerry. Limerick was known for its math curriculum, where some of the teachers were also surveyors. Latin and religion would be taught before mass on Sundays.

When he turned 18 in 1854, it was decided that William would go to America to seek his fortune and hopefully send money back to the family. Based on DNA matches various branches of the family have had in recent years, there seem to have been Carroll cousins in New York and Illinois. Before he left, though, William probably experienced the American Wake.

According to Encyclopedia.com,

The American wake—sometimes called the live wake, farewell supper, or bottle night—was a unique leave-taking ceremony for emigrants from rural Ireland to the United States. American wakes took place prior to the Great Famine, but most evidence survives from the late 1800s and early 1900s, when the custom prevailed among Catholics, especially in western Ireland where traditional customs remained potent. Usually held on the evening prior to an emigrant's departure, the American wake resembled its ceremonial model, the traditional wake for the dead, and its most common name signified that many Catholic country people still regarded emigration as death's equivalent—a permanent breaking of earthly ties. Usually hosted by the emigrant's parents, the American wake, like a traditional wake, was attended by kinfolk and neighbors, featured the liberal consumption of food and drink, and exhibited a seemingly incongruous mixture of grief and gaiety, expressed in lamentations, prayers, games, singing, and dancing.

Although its format was archaic, the American wake was an adaptation to post famine Ireland's social, cultural, and political exigencies. Because emigration was potentially threatening to communal loyalties and values, the leave-taking ceremony interpreted Irish emigration so as to ensure that the emigrants overseas would remain dutiful to the community left behind. The songs, ballads, and other rituals enacted during the American wakes represented a stylized dialogue between the emigrants and the parents, priests, and nationalist politicians who governed Irish Catholic society. Songs that expressed the latter's perspective often ignored the economic causes of emigration and accused the allegedly “selfish,” “hard-hearted” emigrants of “abandoning” their aged mothers and fathers and, by extension, “holy Ireland” itself. In response, the ballads sung from the emigrants' perspective portrayed them not as eager, ambitious, or alienated from Irish poverty or from parental and clerical repression, but as sorrowing “exiles,” victims of British or landlord oppression, who would be miserably homesick overseas until they returned as promised to their parents' hearths. Such songs also excused the emigrants' departures and expiated their guilt by pledging that they would send their parents money from the United States and would remain loyal to their religion and to the cause of Irish freedom. Arguably, then, the harrowing effects of the American wake on young emigrants, at the moment they were leaving home and hence were psychologically most vulnerable, helped to ensure their unusually high levels of remittances, religious fidelity, and nationalist fervor in the New World.

https://www.encyclopedia.com/international/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/american-wakes

In a brilliant performance by an Irish traditional (sean nós) singer Joe Heaney from County Galway, he explained the tradition this way:

What I’m trying to do tonight, in the space I have, is to give you a bit of everything. And the next thing I’m going to do — maybe some of you heard about it, I don’t know — is called The American Wake. Now it’s nothing to do, directly, it’s nothing to do with America. But long ago, when people were going to America and emigrating, their parents knew they’d never see that particular person in this life again.

And the night before they left, the woman or the man who was leaving — It wasn’t so easy then to come home as it is now. They settled down more or less when they went to America, and they got married, and their parents died, meantime they could never see them. But anyway, the man or the woman who was going away visited all the old people in the village, invited them to have a dance that night in the house. And those that weren’t able to go, they gave them a bottle of something as a remembrance.

And they invited the people — Now I’m talking about a time when there was no musical instruments. And of course, long ago, musical instruments were barred, because some of the clergy reckoned that if you played music you were a druid or something — something pagan about you. So maybe it was a good thing, too. But anyway — there was somebody, always, who lilted a tune, and somebody danced to that tune.

Now, in the old country houses they had what was known as a half-door. And sometimes when somebody was dancing on a concrete kitchen floor, they lifted off the half-door, and danced on top of the half-door. Now two of the tunes they used to play was a reel, My Love She’s in America, and a hornpipe, Off to California. This was during the night; and in the morning, of course, the song — the lament — was sung by always — nearly always — the woman. But this is somebody lilting a tune for somebody dancing. My Love She’s in America went something like this:

After lilting the music for the aforementioned, he went on to sing the lament, A stór mo chroí (Treasure of my Heart):

A stór mo chroí, when you’re far away from the home you’ll soon be leaving

And it’s many a time by night and day your heart will be sorely grieving.

Though the stranger’s land might be rich and fair, and riches and treasure golden

You’ll pine, I know, for the long, long ago and the love that’s never olden.

A stór mo chroí, in the stranger’s land there is plenty of wealth and wearing

Whilst gems adorn the rich and the grand there are faces with hunger tearing.

Though the road is dreary and hard to tread, the lights of their city may blind you

You’ll turn, a stór, to Erin’s shore and the ones you left behind you.

A stór mo chroí, when the evening sun over the mountain and meadow is falling

Won’t you turn away from the throng and listen and maybe you’ll hear me calling.

The voice that you’ll hear will be surely mine of somebody’s speedy returning

A rún, a rún, will you come back soon to the one who will always love you.

https://www.joeheaney.org/en/american-wake-the-and-a-stor-mo-chroi/

This link has an audio recording. It is worth a listen.

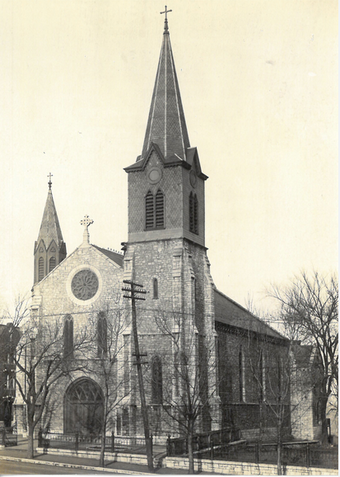

The next morning, the immigrant(s), most likely accompanied by relatives and neighbors, would have traveled on foot to Charleville to purchase a train ticket to Queenstown (now Cobh), Cork, to board a ship bound for New York City. It is possible William was the laborer from Ireland named W. Callaghan who was on the passenger list of the ship States Rights which entered New York on October 22, 1853, but that cannot be verified. According to his biography in The History of Dakota County (1910), William came to New York in 1854 and stayed for three months before moving on to St. Louis. He quickly moved northeast across the Mississippi River and settled in Alton, Illinois, where he had family in Fr. Michael Carroll, the parish priest at Sts. Peter and Paul Church. Michael had actually been responsible for building the church in 1843.

According to The Telegraph.com (https://www.thetelegraph.com/news/article/Saint-Peter-and-Paul-Church-in-need-of-renovation-17277299.php):

In 1843 the Rev. Michael Carroll, who had succeeded Hamilton, built a stone church on the north side of 3rd Street between Alby and Easton streets. In 1853 a fire destroyed the building. For the next three years, services were held in a large hall over Harts Livery Stable at 310 State St., blocks from the recently abandoned state penitentiary. Carroll received $5,000 from fire insurance and $4,000 for the lot and the ruins, leaving an indebtedness of $1,800. The site was purchased by the Unitarians and a church was rebuilt.

On April 7, 1854, a purchase agreement was signed between Peter and Harriet Wise and the Most Rev. Peter Richard Kenrick of St. Louis for a parcel of land. The purchase price was $600.

The church building was started in 1855 and completed in 1857.

William found work at the rock and lime quarry there. In Alton, he met Mary Condon.

Not much is known about Mary’s early life. She was born in 1838 in County Limerick, but the exact date and place is unknown. Her parents were Patrick and Ellen Condon, and she had at least two brothers. In 1852, when she was 14, she, her widowed mother, and her two brothers came to America. By 1860, 22-year-old Mary was living in Alton, Illinois, just across the Mississippi River from St. Louis. She was a domestic servant working for Samuel and Susan Connor. Samuel was a bookkeeper from Maine.

William and Mary married on April 30, 1861, at Sts. Peter and Paul Church in Alton. Their first child, a boy they named John Joseph after William’s father, was born on May 11, 1862, and was baptized at Sts. Peter and Paul Church. Unfortunately, he survived less than three weeks. He was buried from Sts. Peter and Paul on June 1st. Their other eight children would survive and grow to adulthood in Minnesota.

Their second son, Patrick Henry (named for Mary’s father) was born in April of 1864 and baptized in Alton on May 1st. A daughter, Ellen Elizabeth (after her maternal grandmother), was born in 1866, either in Rosemount, Minnesota, or Alton. The 1865 Minnesota Territorial Census shows the family living in Rosemount by June 1st, but Ellen was baptized at Sts. Peter and Paul in Alton on July 22, 1866. Rosemount was where Mary’s brother Michael and her mother Ellen were living. Ellen was not well and would die there in 1865. It is unclear if the permanent move was made in November of 1864 as stated in Mary’s obituary or in 1866 as was stated in William’s biography. Likely the former. Whenever it was, according to William’s biography, the family came to Hastings by boat in order to take up farming. Their fourth child, Mary Ann, was born there in 1868. In 1869, the family moved to Empire Township, where William bought a farm to carry on general farming, stock raising, dairying, and selling cream in Farmington. The rest of the children—Kate (1870), Nora A (1872), William Edward (1973), Maggie E (1875), and James Stephen (1877) —were born in Empire Township.

Dakota County is 587 square miles in area, originally covered with oak prairie savannas. It lies within the confluence of three of the four major rivers draining from the State of Minnesota—the Minnesota and Mississippi Rivers along the northern border and the Mississippi and St. Croix Rivers on the eastern border. Previous to European settlement, Dakota County was part of an expansive territory of the Dakota Sioux tribe.

According to The History of Dakota County (Curtiss-Wedge, 1910), Empire Township received its name from Empire, N. Y., the native place of the wife of one of the early settlers. As early as 1854, claims were staked by the Amidon brothers on the Vermillion river, and two hotels were opened in 1855, one on each side of the river. Called Empire City, a post office was established there, and a store was opened two years later. Alidon Amidon erected his house on the north side of the river, which he opened as another hotel in 1860, and did a rushing business prior to the building of the railroads. The early settlers began to gather in and make claims near this point, and Empire became quite a settlement.

The town was organized as a full congressional township of thirty-six sections, situated in the central part of the county, bounded on the north by Rosemount, on the east by Castle Rock, west by Lakeville. The first white child born in the town was a child of Mr. and Mrs. A. Amidon, 1856. It was also the first death, as the child lived but a short time. The first marriage in the town was that of a German to a Miss Laird, same year. The first school district was organized in 1856, and school was taught in a variety of private homes, including the house that William lived in in 1910.

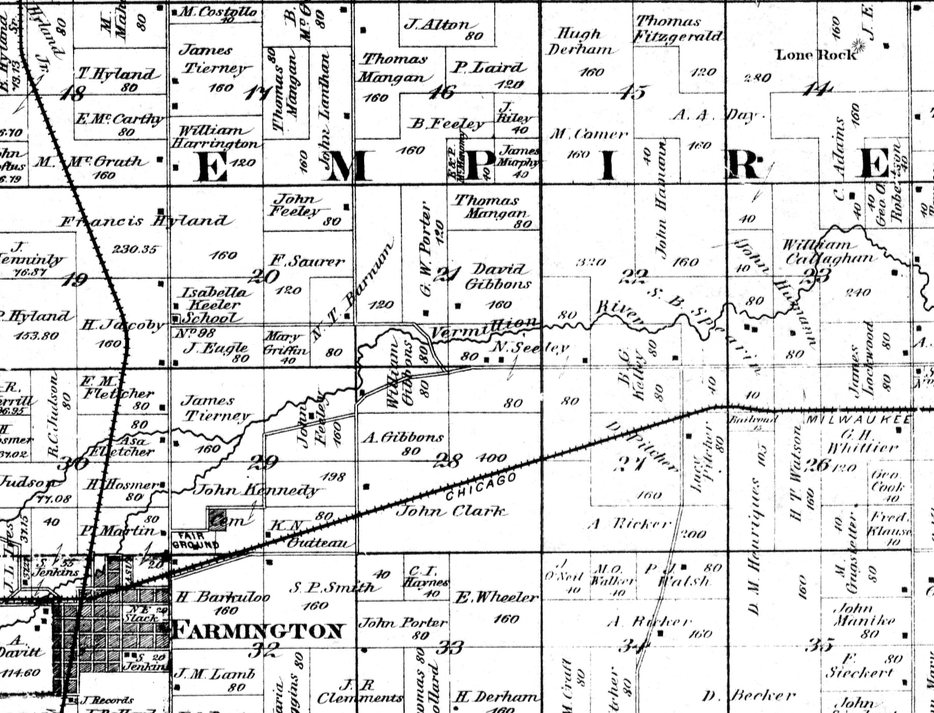

The soil is of rich sandy loam, very productive, and is considered a fair average with the balance of the county. The drainage is somewhat limited and confined to the Vermillion River, which passes through the town from west to east. The two small branches enter from the west on sections 30 and 31, passing through sections 20, 21, 22, 23, and 24. The south branch passes across the southeast corner of section 36. This, together with several small lakes, comprises the drainage of the town. The farm was in section 23, on east edge of the map below.

In 1843 the Rev. Michael Carroll, who had succeeded Hamilton, built a stone church on the north side of 3rd Street between Alby and Easton streets. In 1853 a fire destroyed the building. For the next three years, services were held in a large hall over Harts Livery Stable at 310 State St., blocks from the recently abandoned state penitentiary. Carroll received $5,000 from fire insurance and $4,000 for the lot and the ruins, leaving an indebtedness of $1,800. The site was purchased by the Unitarians and a church was rebuilt.

On April 7, 1854, a purchase agreement was signed between Peter and Harriet Wise and the Most Rev. Peter Richard Kenrick of St. Louis for a parcel of land. The purchase price was $600.

The church building was started in 1855 and completed in 1857.

William found work at the rock and lime quarry there. In Alton, he met Mary Condon.

Not much is known about Mary’s early life. She was born in 1838 in County Limerick, but the exact date and place is unknown. Her parents were Patrick and Ellen Condon, and she had at least two brothers. In 1852, when she was 14, she, her widowed mother, and her two brothers came to America. By 1860, 22-year-old Mary was living in Alton, Illinois, just across the Mississippi River from St. Louis. She was a domestic servant working for Samuel and Susan Connor. Samuel was a bookkeeper from Maine.

William and Mary married on April 30, 1861, at Sts. Peter and Paul Church in Alton. Their first child, a boy they named John Joseph after William’s father, was born on May 11, 1862, and was baptized at Sts. Peter and Paul Church. Unfortunately, he survived less than three weeks. He was buried from Sts. Peter and Paul on June 1st. Their other eight children would survive and grow to adulthood in Minnesota.

Their second son, Patrick Henry (named for Mary’s father) was born in April of 1864 and baptized in Alton on May 1st. A daughter, Ellen Elizabeth (after her maternal grandmother), was born in 1866, either in Rosemount, Minnesota, or Alton. The 1865 Minnesota Territorial Census shows the family living in Rosemount by June 1st, but Ellen was baptized at Sts. Peter and Paul in Alton on July 22, 1866. Rosemount was where Mary’s brother Michael and her mother Ellen were living. Ellen was not well and would die there in 1865. It is unclear if the permanent move was made in November of 1864 as stated in Mary’s obituary or in 1866 as was stated in William’s biography. Likely the former. Whenever it was, according to William’s biography, the family came to Hastings by boat in order to take up farming. Their fourth child, Mary Ann, was born there in 1868. In 1869, the family moved to Empire Township, where William bought a farm to carry on general farming, stock raising, dairying, and selling cream in Farmington. The rest of the children—Kate (1870), Nora A (1872), William Edward (1973), Maggie E (1875), and James Stephen (1877) —were born in Empire Township.

Dakota County is 587 square miles in area, originally covered with oak prairie savannas. It lies within the confluence of three of the four major rivers draining from the State of Minnesota—the Minnesota and Mississippi Rivers along the northern border and the Mississippi and St. Croix Rivers on the eastern border. Previous to European settlement, Dakota County was part of an expansive territory of the Dakota Sioux tribe.

According to The History of Dakota County (Curtiss-Wedge, 1910), Empire Township received its name from Empire, N. Y., the native place of the wife of one of the early settlers. As early as 1854, claims were staked by the Amidon brothers on the Vermillion river, and two hotels were opened in 1855, one on each side of the river. Called Empire City, a post office was established there, and a store was opened two years later. Alidon Amidon erected his house on the north side of the river, which he opened as another hotel in 1860, and did a rushing business prior to the building of the railroads. The early settlers began to gather in and make claims near this point, and Empire became quite a settlement.

The town was organized as a full congressional township of thirty-six sections, situated in the central part of the county, bounded on the north by Rosemount, on the east by Castle Rock, west by Lakeville. The first white child born in the town was a child of Mr. and Mrs. A. Amidon, 1856. It was also the first death, as the child lived but a short time. The first marriage in the town was that of a German to a Miss Laird, same year. The first school district was organized in 1856, and school was taught in a variety of private homes, including the house that William lived in in 1910.

The soil is of rich sandy loam, very productive, and is considered a fair average with the balance of the county. The drainage is somewhat limited and confined to the Vermillion River, which passes through the town from west to east. The two small branches enter from the west on sections 30 and 31, passing through sections 20, 21, 22, 23, and 24. The south branch passes across the southeast corner of section 36. This, together with several small lakes, comprises the drainage of the town. The farm was in section 23, on east edge of the map below.

The Minnesota Central railroad was built to this place in 1864, when the location for the town was made, and settlers began to gather. The Hastings & Dakota railroad was completed to this point, in 1869. This station was called Farmington, as it was wholly a farming country, which seemed appropriate. The Empire post office was transferred to Farmington, and a full fledged city is the result.

The Callaghans might have moved to Minnesota earlier with incentives like the Homestead Act in 1862 and southern Illinois being closer to the Civil War battle front. But there was one good reason not to move north: an Indian war.

On August 17, 1862, four young native men killed five white settlers in Acton, Minnesota. That night, a faction led by Chief Little Crow decided to attack the Lower Sioux Agency the next morning in an effort to drive all settlers out of the Minnesota River valley. In the following weeks, Dakota warriors attacked and killed hundreds of settlers, causing thousands to flee. They also took hundreds of hostages, almost all women and children. The U.S. response was slow because of the Civil War, but on September 23, 1862, an army of volunteer infantry, artillery and citizen militia led by Colonel Henry Hastings Sibley finally defeated Little Crow at the Battle of Wood Lake. The “War” only lasted six weeks.

By the end, 358 settlers had been killed, as well as 116 soldiers and militia. The total number of Dakota casualties is unknown. Approximately 2,000 Dakota surrendered or were taken into custody, including at least 1,658 non-combatants and Native Americans who had opposed the war and helped to free the hostages. Little Crow and a group of more than 150 followers fled to the northern plains of Dakota Territory and Canada. In the aftermath, a military commission, composed of officers from the Minnesota volunteer Infantry, sentenced 303 Dakota men to death. President Lincoln reviewed the convictions and approved death sentences for 39 of them. On December 26, 1862, 38 were hanged in Mankato, Minnesota, with one getting a reprieve. This was the largest one-day mass execution in American history. The United States Congress abolished the eastern Dakota and Ho-Chunk (Winnebago) reservations in Minnesota and declared their treaties null and void. In May 1863, the eastern Dakota and Ho-chunk imprisoned at Fort Snelling were exiled from Minnesota. The Native Americans were placed on riverboats and sent to a reservation in present-day South Dakota. The Ho-Chunk were also initially forced to the Crow Creek reservation, but later moved to Nebraska near the Omaha people to form the Winnebago Reservation.

By the end of the Civil War, farming in Minnesota seemed like a more viable option than rock quarry work in southern Illinois. Another reason for the move was “King Wheat.”

Minnesota farmers first started planting wheat during the territorial days of the early 1850s. They also cultivated corn, oats, and produce for their own use or barter, but wheat was their cash crop. By 1860, small mills scattered around the state supplied flour to local markets. The numbers of Minnesota mills grew rapidly. However, wheat farmers were producing an excess of grain that could be sold for cash and shipped to other markets. The grain brought needed money into the farmers' hands. Dakota County was one of eight that produced more than 100,000 bushels of wheat in 1860.

The milling industry continued to grow throughout the 1860s, despite the scourge of the Civil War. By 1870, the state had 507 flour mills, mostly in the southeast. Statewide, farmers grew wheat on more than 61 percent of the cultivated acreage.

The Callaghan farm started out slow. According to the 1870 US Non-Population Census, William and Mary only had 80 acres of improved land, two horses, two mules and a pig. The land was worth $1200, and the livestock $400. In the Spring, they had gathered 1000 bushels of wheat, 300 bushels of oats, 3 bushels of hay, and 18 bushels of Irish potatoes. But the soil was of rich sandy loam and very productive. By 1879, William owned 240 acres and commensurate livestock and crops.

The King Wheat era did not last in Minnesota's once-booming, southeastern wheat-producing counties. A St. Paul Pioneer Press report on July 21, 1878, noted numerous samples of wheat from all parts of Goodhue County showing heavy blight. A black rust covered stalks of wheat from the head down several inches. A week later the Pioneer Press spoke of a general failure in the wheat crop in southeastern Minnesota and northern Iowa. Minnesota wheat yields in the fall of 1878 averaged twelve bushels per acre, much lower in the southeastern counties. State farmers continued to produce wheat but slowly began to diversify their operations to stay profitable. Malting barley became the new cash crop and dairying grew in popularity.

William became a prominent member of the community and became active politically like other members of the family. He was a road overseer like his brother Patrick in New Zealand and nephew John in California. He was a member the school board like his brother Michael in California. He even was elected town supervisor, a height only he reached.

In 1895, William’s brother Michael and his wife visited from California. It was the first and only time that he had seen any of his siblings in over forty years. It was the only time Michael left California.

Despite having eight children who survived childhood, the family growth would stop there. Of the eight, only Maggie would marry, which she did at the age of 33 in 1908. But she never had any children and her husband died in 1914. William and Mary would have no grandchildren.

The Callaghans might have moved to Minnesota earlier with incentives like the Homestead Act in 1862 and southern Illinois being closer to the Civil War battle front. But there was one good reason not to move north: an Indian war.

On August 17, 1862, four young native men killed five white settlers in Acton, Minnesota. That night, a faction led by Chief Little Crow decided to attack the Lower Sioux Agency the next morning in an effort to drive all settlers out of the Minnesota River valley. In the following weeks, Dakota warriors attacked and killed hundreds of settlers, causing thousands to flee. They also took hundreds of hostages, almost all women and children. The U.S. response was slow because of the Civil War, but on September 23, 1862, an army of volunteer infantry, artillery and citizen militia led by Colonel Henry Hastings Sibley finally defeated Little Crow at the Battle of Wood Lake. The “War” only lasted six weeks.

By the end, 358 settlers had been killed, as well as 116 soldiers and militia. The total number of Dakota casualties is unknown. Approximately 2,000 Dakota surrendered or were taken into custody, including at least 1,658 non-combatants and Native Americans who had opposed the war and helped to free the hostages. Little Crow and a group of more than 150 followers fled to the northern plains of Dakota Territory and Canada. In the aftermath, a military commission, composed of officers from the Minnesota volunteer Infantry, sentenced 303 Dakota men to death. President Lincoln reviewed the convictions and approved death sentences for 39 of them. On December 26, 1862, 38 were hanged in Mankato, Minnesota, with one getting a reprieve. This was the largest one-day mass execution in American history. The United States Congress abolished the eastern Dakota and Ho-Chunk (Winnebago) reservations in Minnesota and declared their treaties null and void. In May 1863, the eastern Dakota and Ho-chunk imprisoned at Fort Snelling were exiled from Minnesota. The Native Americans were placed on riverboats and sent to a reservation in present-day South Dakota. The Ho-Chunk were also initially forced to the Crow Creek reservation, but later moved to Nebraska near the Omaha people to form the Winnebago Reservation.

By the end of the Civil War, farming in Minnesota seemed like a more viable option than rock quarry work in southern Illinois. Another reason for the move was “King Wheat.”

Minnesota farmers first started planting wheat during the territorial days of the early 1850s. They also cultivated corn, oats, and produce for their own use or barter, but wheat was their cash crop. By 1860, small mills scattered around the state supplied flour to local markets. The numbers of Minnesota mills grew rapidly. However, wheat farmers were producing an excess of grain that could be sold for cash and shipped to other markets. The grain brought needed money into the farmers' hands. Dakota County was one of eight that produced more than 100,000 bushels of wheat in 1860.

The milling industry continued to grow throughout the 1860s, despite the scourge of the Civil War. By 1870, the state had 507 flour mills, mostly in the southeast. Statewide, farmers grew wheat on more than 61 percent of the cultivated acreage.

The Callaghan farm started out slow. According to the 1870 US Non-Population Census, William and Mary only had 80 acres of improved land, two horses, two mules and a pig. The land was worth $1200, and the livestock $400. In the Spring, they had gathered 1000 bushels of wheat, 300 bushels of oats, 3 bushels of hay, and 18 bushels of Irish potatoes. But the soil was of rich sandy loam and very productive. By 1879, William owned 240 acres and commensurate livestock and crops.

The King Wheat era did not last in Minnesota's once-booming, southeastern wheat-producing counties. A St. Paul Pioneer Press report on July 21, 1878, noted numerous samples of wheat from all parts of Goodhue County showing heavy blight. A black rust covered stalks of wheat from the head down several inches. A week later the Pioneer Press spoke of a general failure in the wheat crop in southeastern Minnesota and northern Iowa. Minnesota wheat yields in the fall of 1878 averaged twelve bushels per acre, much lower in the southeastern counties. State farmers continued to produce wheat but slowly began to diversify their operations to stay profitable. Malting barley became the new cash crop and dairying grew in popularity.

William became a prominent member of the community and became active politically like other members of the family. He was a road overseer like his brother Patrick in New Zealand and nephew John in California. He was a member the school board like his brother Michael in California. He even was elected town supervisor, a height only he reached.

In 1895, William’s brother Michael and his wife visited from California. It was the first and only time that he had seen any of his siblings in over forty years. It was the only time Michael left California.

Despite having eight children who survived childhood, the family growth would stop there. Of the eight, only Maggie would marry, which she did at the age of 33 in 1908. But she never had any children and her husband died in 1914. William and Mary would have no grandchildren.

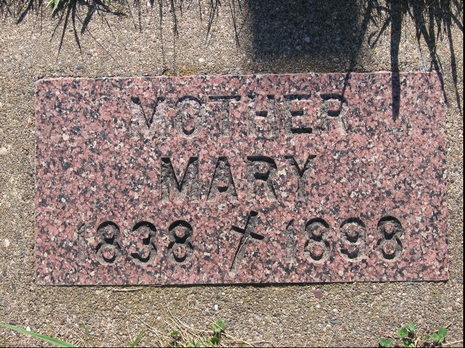

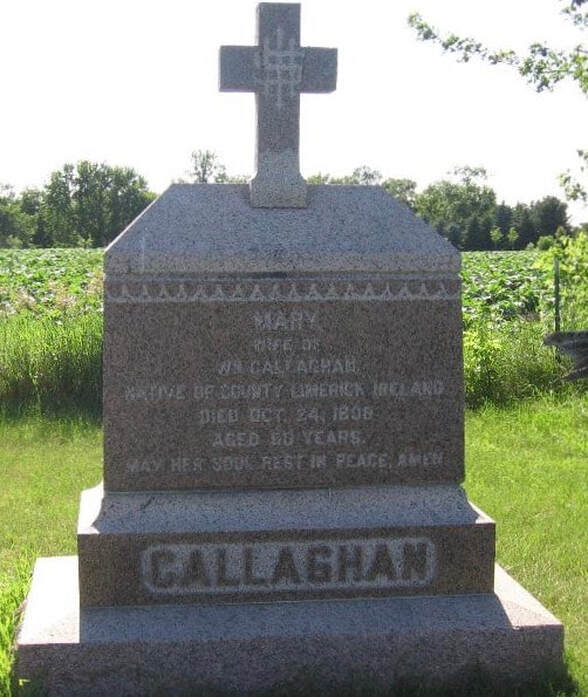

On October 14, 1898, Mary Condon passed away at their home in Inver Grove, Minnesota. She was 60 years old. She had been ill for sixteen months and was in constant pain. Her obituary said that few outside her home realized what a good wife and mother she had been, but everyone knew what a good neighbor she was, “with a kind word for everyone, being of a natural cheerful disposition.” Her death was a relief. After a funeral mass at St. Agatha’s Church officiated by Fr William McGoldrick, she was laid to rest in St. Agatha’s Cemetery, Vermillion.

William outlived his wife by 26 years. He never remarried, but his children mostly lived nearby. His daughters were all teachers in local schools, except Maggie, who moved to Montana with her husband and to California after his death and worked in a government job. The years were not all happy, though. In 1916, William lost both his son Patrick and daughter Nora to pneumonia. He also outlived all but his youngest sibling.

William outlived his wife by 26 years. He never remarried, but his children mostly lived nearby. His daughters were all teachers in local schools, except Maggie, who moved to Montana with her husband and to California after his death and worked in a government job. The years were not all happy, though. In 1916, William lost both his son Patrick and daughter Nora to pneumonia. He also outlived all but his youngest sibling.

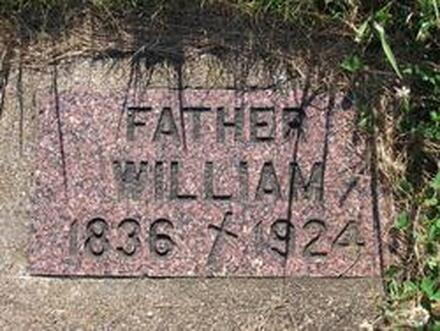

At Inver Grove, on Sunday February 17, 1924, William died of heart trouble. His death was “unexpected and came as a shock to his family and friends.” He was 88 years old. He was the second longest-lived of the Callaghans of Effin, only to be outdone by his youngest brother James who died at 94 years old. The funeral service was held at St. Michael’s Church, Fr. D.J. Moran officiating. He was buried with his wife and children in St. Agatha’s Cemetery.

In his last will and testament, dated February 20, 1911, William named his daughter Mary as the executrix of his estate. He left $800 to each of his children, except Nellie who received $2500. Patrick was to receive the farm and all its cattle, tools and grain with the expressed understanding that he would sell it all off within two years and the proceeds would be split among the three sons. Patrick, unfortunately, died eight years before his father.

William and Mary lived the American Dream. They were poor immigrants fleeing economic stresses who found each other and built a prosperous life together. But as the truest Ghost Family among the descendants of John and Nora Callaghan, they did not just go from rags to riches back to rags in three generations, they went from rags to riches to extinction. There was no third generation in this branch, despite eight children surviving to adulthood. The next phase just was not meant to be.

William and Mary lived the American Dream. They were poor immigrants fleeing economic stresses who found each other and built a prosperous life together. But as the truest Ghost Family among the descendants of John and Nora Callaghan, they did not just go from rags to riches back to rags in three generations, they went from rags to riches to extinction. There was no third generation in this branch, despite eight children surviving to adulthood. The next phase just was not meant to be.