John Callaghan and Nora Carroll

Name: John Callaghan

Birth: 1816, Kilbreedy Minor, Co Limerick, Ireland

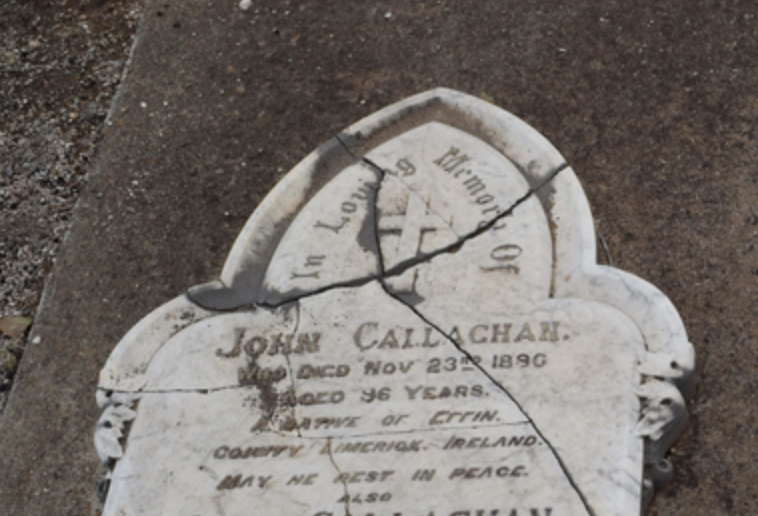

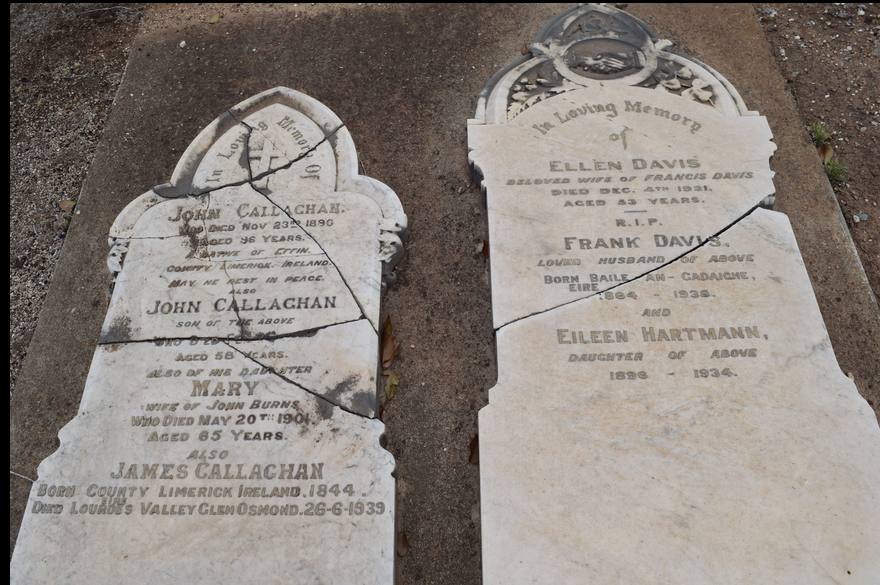

Death: 23 November 1890, Hectorville, Adelaide, South Australia

Burial: St. Joseph's Cemetery, Rio Vista

Father: William Callaghan

Mother: Unknown

Spouse: Hanora Mary Carroll

Birth: 1818, Effin, Co Limerick, Ireland

Death: about 1857, Effin, Co Limerick, Ireland

Father: Michael Carroll

Mother: unknown

Marriage: About 1835, Effin, Co Limerick, Ireland

Children: 1.1 William (1837-1924)

1.2 Mary Ann (1836-1901)

1.3 Michael (1838-1920)

1.4 Ellen (1840-?)

1.5 Patrick (1841-1907)

1.6 John (1842-1901)

1.7 James (1844-1938)

1.8 Kate (1850-?)

Spouse: Mary Anne Cleary Philips

Birth: abt 1827, Ennis, Clare, Ireland

Death: Norton, South Australia

Father: John Cleary

Mother: Margaret Aspell

Marriage: 2 Feb 1866, St. Patrick’s Chapel, Adelaide, South Australia

The name Callaghan comes from Ceallachain, King of Munster, who was the Eóganachta King of Munster from AD 935 until 954. The personal name Cellach means ‘bright-headed.’ The principal Munster sept of the name Callaghan were lords of Cineál Aodha in South Cork originally. This area is west of Mallow along the Blackwater River valley. The family were dispossessed of their ancestral home and 24,000 acres by the Cromwellian Plantation and settled in East Clare.

The O'Callaghan land near Mallow, forfeited by Donough O'Callaghan after the Irish rebellion of 1641, came into the hands of a family called Longfield or Longueville, who built a 20-bedroom Georgian mansion there. In a twist of history, 500 acres of the ancient O'Callaghan land returned to O'Callaghan hands in the twentieth century, when Longueville House was bought by a descendant of Donough O'Callaghan. The ancestral estate of the O'Callaghans, now a luxury hotel, is owned by William O'Callaghan. In 1994, Don Juan O'Callaghan of Tortosa was recognized by the Genealogical Office as the senior descendant in the male line of the last inaugurated O'Callaghan. The Callaghan family motto is Fidus et Audax—"Faithful and Bold.”

Carroll is an Irish surname coming from the Gaelic Ó Cearbhaill and Cearbhall, often translated as “fierce in battle” but perhaps is based on cearbh ‘hacking’ of ‘slaughter’ and, hence, originally was a byname for a butcher or a fierce warrior. Their motto is In Fide et in Bello Fortis, Strong in Faith and in Battle.

The O’Carrolls of the Ely O’Carroll clan claimed descent from Olioll Ollum, a third century king of Munster, and Sadhbh, the daughter of Conn Cétchathach (Conn of the Hundred Battles). Also known as the Ely and Clan Cian, it may have begun with Cearbhaill, the King of Ely, who fought with Brian Boru at the Battle of Clontarf in 1014. Donald O’Carroll was King of Ely at the coming of the English under Strongbow and was the forebear of the main lines of the family. The Carroll clan is best known for its ties to the region known as Ely O’Carroll country, an area comprising mostly of county Offaly and North Tipperary. Locations such as the Slieve Bloom mountains and towns such as Birr in Offaly and Roscrea in Tipperary have had close links to the Ely O’Carrolls. There were many castles associated with them, the most famous or possibly the most notorious being Leap Castle.

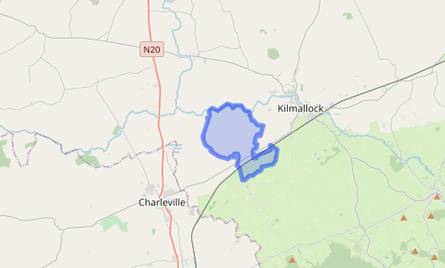

It is believed that John Callaghan was born between July 1815 and June 1816. His father's name was William Callaghan and, while his mother’s name is not known for sure, based on traditional family naming patterns, she may have been named Ellen. Land records and court documents show that John was born and raised in Kilbreedy Minor, Mount Blakeney, on the Limerick-Cork border. Charleville was the largest nearby town.

According to Lewis’ A Topological Map of Ireland (1837), Kilbreedy Minor:

Birth: 1816, Kilbreedy Minor, Co Limerick, Ireland

Death: 23 November 1890, Hectorville, Adelaide, South Australia

Burial: St. Joseph's Cemetery, Rio Vista

Father: William Callaghan

Mother: Unknown

Spouse: Hanora Mary Carroll

Birth: 1818, Effin, Co Limerick, Ireland

Death: about 1857, Effin, Co Limerick, Ireland

Father: Michael Carroll

Mother: unknown

Marriage: About 1835, Effin, Co Limerick, Ireland

Children: 1.1 William (1837-1924)

1.2 Mary Ann (1836-1901)

1.3 Michael (1838-1920)

1.4 Ellen (1840-?)

1.5 Patrick (1841-1907)

1.6 John (1842-1901)

1.7 James (1844-1938)

1.8 Kate (1850-?)

Spouse: Mary Anne Cleary Philips

Birth: abt 1827, Ennis, Clare, Ireland

Death: Norton, South Australia

Father: John Cleary

Mother: Margaret Aspell

Marriage: 2 Feb 1866, St. Patrick’s Chapel, Adelaide, South Australia

The name Callaghan comes from Ceallachain, King of Munster, who was the Eóganachta King of Munster from AD 935 until 954. The personal name Cellach means ‘bright-headed.’ The principal Munster sept of the name Callaghan were lords of Cineál Aodha in South Cork originally. This area is west of Mallow along the Blackwater River valley. The family were dispossessed of their ancestral home and 24,000 acres by the Cromwellian Plantation and settled in East Clare.

The O'Callaghan land near Mallow, forfeited by Donough O'Callaghan after the Irish rebellion of 1641, came into the hands of a family called Longfield or Longueville, who built a 20-bedroom Georgian mansion there. In a twist of history, 500 acres of the ancient O'Callaghan land returned to O'Callaghan hands in the twentieth century, when Longueville House was bought by a descendant of Donough O'Callaghan. The ancestral estate of the O'Callaghans, now a luxury hotel, is owned by William O'Callaghan. In 1994, Don Juan O'Callaghan of Tortosa was recognized by the Genealogical Office as the senior descendant in the male line of the last inaugurated O'Callaghan. The Callaghan family motto is Fidus et Audax—"Faithful and Bold.”

Carroll is an Irish surname coming from the Gaelic Ó Cearbhaill and Cearbhall, often translated as “fierce in battle” but perhaps is based on cearbh ‘hacking’ of ‘slaughter’ and, hence, originally was a byname for a butcher or a fierce warrior. Their motto is In Fide et in Bello Fortis, Strong in Faith and in Battle.

The O’Carrolls of the Ely O’Carroll clan claimed descent from Olioll Ollum, a third century king of Munster, and Sadhbh, the daughter of Conn Cétchathach (Conn of the Hundred Battles). Also known as the Ely and Clan Cian, it may have begun with Cearbhaill, the King of Ely, who fought with Brian Boru at the Battle of Clontarf in 1014. Donald O’Carroll was King of Ely at the coming of the English under Strongbow and was the forebear of the main lines of the family. The Carroll clan is best known for its ties to the region known as Ely O’Carroll country, an area comprising mostly of county Offaly and North Tipperary. Locations such as the Slieve Bloom mountains and towns such as Birr in Offaly and Roscrea in Tipperary have had close links to the Ely O’Carrolls. There were many castles associated with them, the most famous or possibly the most notorious being Leap Castle.

It is believed that John Callaghan was born between July 1815 and June 1816. His father's name was William Callaghan and, while his mother’s name is not known for sure, based on traditional family naming patterns, she may have been named Ellen. Land records and court documents show that John was born and raised in Kilbreedy Minor, Mount Blakeney, on the Limerick-Cork border. Charleville was the largest nearby town.

According to Lewis’ A Topological Map of Ireland (1837), Kilbreedy Minor:

A parish in the barony of Coshma, county Limerick, and Province of Munster, 2 miles [south southwest] from Kilmallock, and on the road from that place to Charleville; containing 600 inhabitants. It comprises 2087 statute acres, as applotted under the tithe act: the soil is very good, but only about one-fifth of it is under tillage, the remainder being meadow or pasture land. The living is a rectory and vicarage. In the Diocese of Limerick, and in the gift of the Bishop: the tithes amount to 130. In the Roman Catholic divisions, the parish forms part of. The union or district of Effin. Near the south bank of the Subtach are the ruins of the old church.

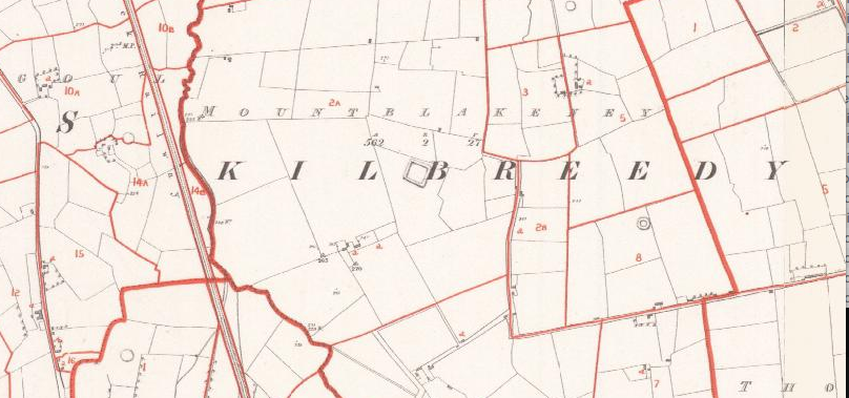

The Callaghan land was at the northwest end of the parish.

Nothing is known of John’s early life. He would have grown up working on the farm and may also have been one of the 90 children known to have attended the two Hedge Schools.

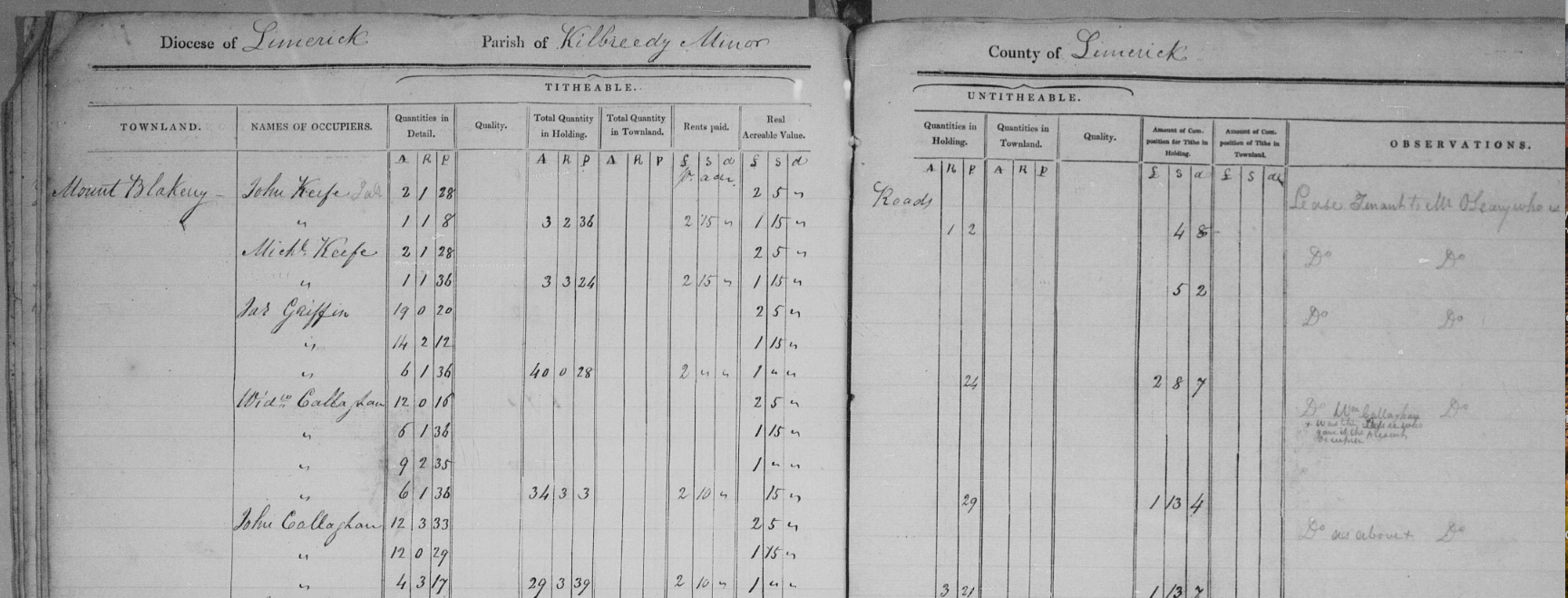

The 1833 Tithe Applotment Book shows 17-year-old John was renting 29 acres of land on Lady Gertrude Fitzgerald’s estate, adjacent to where his mother (the “Widow Callaghan”) was renting 34 acres. Her husband had previously rented all 53 acres and, according to later statements by John, the land had been worked by the family for over a century. Where the Callaghans had been before that is unknown.

The Callaghan land was at the northwest end of the parish.

Nothing is known of John’s early life. He would have grown up working on the farm and may also have been one of the 90 children known to have attended the two Hedge Schools.

The 1833 Tithe Applotment Book shows 17-year-old John was renting 29 acres of land on Lady Gertrude Fitzgerald’s estate, adjacent to where his mother (the “Widow Callaghan”) was renting 34 acres. Her husband had previously rented all 53 acres and, according to later statements by John, the land had been worked by the family for over a century. Where the Callaghans had been before that is unknown.

According to Burke's Irish Family Records, William Blakeney was granted lands at Thomastown, parish of Kilbreedy Minor, by patent of Charles II in 1666/7. Blakeney was a well-decorated career military man who seems to have never spent time in Thomastown. His son William Blakeney married Elizabeth Bowerman of Cooliney, Cork, and their eldest son was created 1st [and only] Baron Blakeney in 1756. The Baron died without children, and the land passed through his younger brother Robert to his great grandniece, Lady Gertrude Fitzgerald. She employed the Dublin firm of Stewart & Kincaid (SK) to manage the land for her.

It is unknown when and how John met Nora Carroll.

No photo available

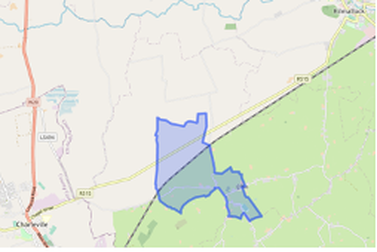

Hanora Mary Carroll was born around 1818 in Effin, Limerick. Her father was Michael Carroll and her mother might have been Mary or Ellen. According to the Tithe Applotment Books of 1828 and 1829, Michael rented 67 acres of land in Effin. According to Lewis’ A Topological Map of Ireland (1837), Effin was:

a parish, partly in the barony of Costlea, but chiefly in that of Coshma, county of Limerick, and province of MUNSTER, 1 3⁄4 mile S. S. W.) from Kilmallock, on the road to Charleville; containing 2090 inhabitants, and comprising 8281 statute acres, of which 5138 are applotted under the tithe act. The land is excellent and much under tillage, and the mountain pasture good; the meadows attached to dairy farms are very productive. Newpark is the residence of J. Balie, Esq,; and Maiden Hall, of R. Low Holmes, Esq. It is a rectory and vicarage, in the diocese of Limerick, constituting the corps of the prebend of Effin in the cathedral of Limerick, and in the patronage of the Earl of Dunraven; the tithes amount to £320, and there is a glebe of seven acres. The church is in ruins, and the inhabitants attend that of Kilmallock. In the R. C. divisions, it is united with those of Kilbreedy-minor and Kilquane; there are two small chapels, one at Effin, the other at Kilbreedy. About 90 children are taught in two hedge schools.

Michael may have rented from either Windham Henry Quin, 2nd Earl of Dunraven, or, later, from land owner Robert Maxwell or from one of Maxwell’s three main Effin tenants—Connor Moynahan, John Herlehy, or Jeremiah Hannigan. By the 1850s, his sons were renting from Robert O’Grady.

Local tradition has it that the first church at Effin was founded in the 6th Century by St. Eimhin, son of Eoghan McMurchad of Munster near the site of an ancient holy well, which he rededicated to the Blessed Virgin. He later moved to Co. Kildare to form a monastery and as a result the town of Monasterevin was formed. According to the Effin and Glengarrick Parish History:

Effin had a Norman manor, located in the town land of Tobernea, it was in a field near Leos farm near Macs cross. Nothing remains now of the castle except what’s documented on ordinance survey maps. It appears to have been an important place in its time around the area. In the Thirteenth century the Manor of Tiberneyum (Tobbernea) was an important castle at the time holding a weekly market weekly market every Tuesday and a yearly fair lasting for six days from August 27th to September 3rd.

It is unknown when and how John met Nora Carroll.

No photo available

Hanora Mary Carroll was born around 1818 in Effin, Limerick. Her father was Michael Carroll and her mother might have been Mary or Ellen. According to the Tithe Applotment Books of 1828 and 1829, Michael rented 67 acres of land in Effin. According to Lewis’ A Topological Map of Ireland (1837), Effin was:

a parish, partly in the barony of Costlea, but chiefly in that of Coshma, county of Limerick, and province of MUNSTER, 1 3⁄4 mile S. S. W.) from Kilmallock, on the road to Charleville; containing 2090 inhabitants, and comprising 8281 statute acres, of which 5138 are applotted under the tithe act. The land is excellent and much under tillage, and the mountain pasture good; the meadows attached to dairy farms are very productive. Newpark is the residence of J. Balie, Esq,; and Maiden Hall, of R. Low Holmes, Esq. It is a rectory and vicarage, in the diocese of Limerick, constituting the corps of the prebend of Effin in the cathedral of Limerick, and in the patronage of the Earl of Dunraven; the tithes amount to £320, and there is a glebe of seven acres. The church is in ruins, and the inhabitants attend that of Kilmallock. In the R. C. divisions, it is united with those of Kilbreedy-minor and Kilquane; there are two small chapels, one at Effin, the other at Kilbreedy. About 90 children are taught in two hedge schools.

Michael may have rented from either Windham Henry Quin, 2nd Earl of Dunraven, or, later, from land owner Robert Maxwell or from one of Maxwell’s three main Effin tenants—Connor Moynahan, John Herlehy, or Jeremiah Hannigan. By the 1850s, his sons were renting from Robert O’Grady.

Local tradition has it that the first church at Effin was founded in the 6th Century by St. Eimhin, son of Eoghan McMurchad of Munster near the site of an ancient holy well, which he rededicated to the Blessed Virgin. He later moved to Co. Kildare to form a monastery and as a result the town of Monasterevin was formed. According to the Effin and Glengarrick Parish History:

Effin had a Norman manor, located in the town land of Tobernea, it was in a field near Leos farm near Macs cross. Nothing remains now of the castle except what’s documented on ordinance survey maps. It appears to have been an important place in its time around the area. In the Thirteenth century the Manor of Tiberneyum (Tobbernea) was an important castle at the time holding a weekly market weekly market every Tuesday and a yearly fair lasting for six days from August 27th to September 3rd.

Tobbermea Castle was granted by King John to Philip de Prendergast in 1207. In 1287, Effin became the prebend (source of an annual stipend) of the Church of Limerick. In the 1560’s, the old parish of Effin, Kilquane and Kilbreedy-Minor became protestant parishes. Edmund Spencer, the famous Elizabethan poet, had been mentioned as being a prebend of Effin parish: “Collection of the arrearages of first fruits. These contain the names of many of the clergy of the time, amongst others, Edmondus Spenser, prebendary of Effin.” An extensive mapping of Ireland was carried out by William Petty in 1655 and 1656, after the Cromwellian Conquest. The government had to pay many of the adventurers and soldiers for their support in the wars in Ireland, and they were to be repaid using the confiscated lands. Petty listed the “lists Parish of Effyne,” as being owned by George Earl of Kildare.

John and Nora were married in Effin Church sometime around 1836 and had at least seven children. First came a daughter they named Mary and a son named William, both in 1837. They might have been twins or separated by 11 months. It is also possible that the William on the passenger list to South Australia was John’s brother rather than his son, since statements about his age are inconsistent. Their son Michael was born on April 10, 1838, and was named after his maternal grandfather. Ellen was born in about 1840, Patrick about 1841, and John about 1842. Baptismal records for the first six children do not exist, though Michael’s marriage certificate says he was baptized at Effin Church. James was born at the end of summer two years later and baptized at Effin Church on August 31, 1844. His godparents were William Callaghan and Margaret Keeffe. Finally, Kate was born in 1850 and baptized on June 16, 1950. Her godparents were William Callaghan and Ellen Carroll.

Life in the 1830s and 1840s was difficult all over Ireland and especially so in the South West. By 1843, many of the estates in Ireland had become overcrowded and difficult to manage, with subletting a common occurrence. Mrs. Fitzgerald—through Stewart & Kincaid (SK) —decided to clean things up as several of the leases with middlemen had come up for renewal. Some of the subtenants lost their lease and were moved out, though most we compensated. This reallocation of lands was known as “squaring the lands,” and it was being done all over Ireland. In many places (like Lord Clonbrock’s lands which the Rafterys rented in Galway), it would make the difference between survival and failure over the next few years.

The Stewart & Kincaid archives were released in the early 1990s and came into the possession of University College Dublin’s Department of Economics, where they were thoroughly researched by Desmond Norton, PhD. In 2002, Norton published a working paper called Distress and Benevolence on Gertrude Fitzgerald’s Limerick Estate in the 1840s. Most of the following information is condensed from that paper and/or Norton’s follow-up book of the same name. As Norton wrote,

In connection with squaring the lands, John Callaghan was a troublesome tenant. The broad facts in regard to him were as follows: Early in 1844 he received £15 from SK on the understanding that he would promptly surrender his land. Around the same time, John Bernard was assigned a portion of Callaghan’s land. Furthermore, it was agreed that John Bernard would pay Callaghan £4 for having planted crops there. But by March 1844, Callaghan had changed his mind: he now refused to surrender the farm. On 21 March, Murnane reported to SK: “I got possession from Keefe and Michael Bernard and paid them their money. I gave Bernard’s part to his Brother .... Callaghan will not give up the possession.”

“Murnane” was John Murnane, a tenant on the nearby Bruce estate who had been appointed bailiff for the Fitzgerald estate. Bernard did not pay the £4, so John would not let him on the land. In August, 1844, Bernard took John to Kilmallock Petty Court, for “malicious trespass, and a second charge for being in dread of killing him and setting fire to his house.” John was acquitted, though.

John did make several peaceful attempts to get SK to let him stay on the land. He wrote them letters explaining his situation. He wrote to Kincaid’s wife:

From the reply of your respected Husband [Joseph] Kincaid Esqr. that my letter of the 8th Inst. did not meet his or your Ladyship's approbation ... I am now deprived of any future hope for my poor wife and six helpless children .... I did not think it imprudent to solicit your Ladyship's intercession on my behalf to Mr Kincaid .... If pity ever was extended towards an honest industrious and indignant family, let it now prevail .... Say something in my favour.

He even walked the 60 miles from Mount Blakeney to Mrs. Fitzgerald’s home in Cloyne in southeast Cork to petition her directly. She referred the matter back to SK, suggesting they raise their offer and resolve the situation quietly. Murnane, who was a piece of work, would later be accused by an SK employee of “being behaving very ill ... and states ... that poor John Callaghan against whom we had to bring Ejectments last assizes was put up by Murnane to set the part he did.”

John and Nora were married in Effin Church sometime around 1836 and had at least seven children. First came a daughter they named Mary and a son named William, both in 1837. They might have been twins or separated by 11 months. It is also possible that the William on the passenger list to South Australia was John’s brother rather than his son, since statements about his age are inconsistent. Their son Michael was born on April 10, 1838, and was named after his maternal grandfather. Ellen was born in about 1840, Patrick about 1841, and John about 1842. Baptismal records for the first six children do not exist, though Michael’s marriage certificate says he was baptized at Effin Church. James was born at the end of summer two years later and baptized at Effin Church on August 31, 1844. His godparents were William Callaghan and Margaret Keeffe. Finally, Kate was born in 1850 and baptized on June 16, 1950. Her godparents were William Callaghan and Ellen Carroll.

Life in the 1830s and 1840s was difficult all over Ireland and especially so in the South West. By 1843, many of the estates in Ireland had become overcrowded and difficult to manage, with subletting a common occurrence. Mrs. Fitzgerald—through Stewart & Kincaid (SK) —decided to clean things up as several of the leases with middlemen had come up for renewal. Some of the subtenants lost their lease and were moved out, though most we compensated. This reallocation of lands was known as “squaring the lands,” and it was being done all over Ireland. In many places (like Lord Clonbrock’s lands which the Rafterys rented in Galway), it would make the difference between survival and failure over the next few years.

The Stewart & Kincaid archives were released in the early 1990s and came into the possession of University College Dublin’s Department of Economics, where they were thoroughly researched by Desmond Norton, PhD. In 2002, Norton published a working paper called Distress and Benevolence on Gertrude Fitzgerald’s Limerick Estate in the 1840s. Most of the following information is condensed from that paper and/or Norton’s follow-up book of the same name. As Norton wrote,

In connection with squaring the lands, John Callaghan was a troublesome tenant. The broad facts in regard to him were as follows: Early in 1844 he received £15 from SK on the understanding that he would promptly surrender his land. Around the same time, John Bernard was assigned a portion of Callaghan’s land. Furthermore, it was agreed that John Bernard would pay Callaghan £4 for having planted crops there. But by March 1844, Callaghan had changed his mind: he now refused to surrender the farm. On 21 March, Murnane reported to SK: “I got possession from Keefe and Michael Bernard and paid them their money. I gave Bernard’s part to his Brother .... Callaghan will not give up the possession.”

“Murnane” was John Murnane, a tenant on the nearby Bruce estate who had been appointed bailiff for the Fitzgerald estate. Bernard did not pay the £4, so John would not let him on the land. In August, 1844, Bernard took John to Kilmallock Petty Court, for “malicious trespass, and a second charge for being in dread of killing him and setting fire to his house.” John was acquitted, though.

John did make several peaceful attempts to get SK to let him stay on the land. He wrote them letters explaining his situation. He wrote to Kincaid’s wife:

From the reply of your respected Husband [Joseph] Kincaid Esqr. that my letter of the 8th Inst. did not meet his or your Ladyship's approbation ... I am now deprived of any future hope for my poor wife and six helpless children .... I did not think it imprudent to solicit your Ladyship's intercession on my behalf to Mr Kincaid .... If pity ever was extended towards an honest industrious and indignant family, let it now prevail .... Say something in my favour.

He even walked the 60 miles from Mount Blakeney to Mrs. Fitzgerald’s home in Cloyne in southeast Cork to petition her directly. She referred the matter back to SK, suggesting they raise their offer and resolve the situation quietly. Murnane, who was a piece of work, would later be accused by an SK employee of “being behaving very ill ... and states ... that poor John Callaghan against whom we had to bring Ejectments last assizes was put up by Murnane to set the part he did.”

Another less peaceful way, though, was that John and his “people-in-law” cut and stole Bernard’s field of oats. When Murnane came with three constables to arrest him, John and the Carrolls were ready:

Callaghan and the Carrolls ... cut two acres and half of Bernards oats yesterday and carried it off the lands. I went myself on the lands to protect the oats being

carried off, but all in vain. I had three of the police from Kilmallock with me and ... we were beattin off with stones and sickels. They were in number more than 70 men and women .... I went from the lands to Kilfinane [about 8 miles away] to get more police .... Four of them were taken and bailed for Friday which is the Court day in Kilmallock

The charges were dropped again. The next March, Murnane came again with another bailiff to talk John into leaving the land, but John allegedly grabbed a pike and threatened to run anyone through who came near him. On May 13, John again wrote SK:

Is there anything more unfair ... than to take the part of one man having a large family and whose Ancestors have lived on this Estate for the last Century, and hand it over to another [John Bernard] ... who has no original claim, save his being a Lot holder ... to the late Thomas White [a middleman] .... Leave me my little holding and you shall be honestly repaid what money you gave me

SK wrote to Murnane to offer more money, but Murnane refused and had John arrested again. The charges are unknown, but Murnane now sought an ejectment decree.

Stewart Maxwell, a senior employee of SK, decided to visit Callaghan in jail. He reported that "the fellow is in a wretched state of mind and says that ... he does not care very much what happens to him"; however, "he at last consented to take £15 and to get his potatoes" in return for quietly giving up possession. It seems, following further pressure from Bennett, that the case against Callaghan was struck off the list.

On August 7, 1845, Murnane informed SK that he had gotten John off the land, seized anything worthwhile, and left seven men on the land to guard it at night. On the 10th, he wrote:

the state of Callaghan's former lands, as follows: “2 acres of Bad oats, 1 ½ ditto of potatoes, ½ meaddowing, 3 ¼ ditto pasture or waist land.

John was off the final 7.25 acres of the land, but not off the estate. He moved his family into a bothán (a fourth-class house which was a mere hovel made of mud and sticks) owned by neighbor John Keeffe, probably related to his son James’ godmother. Then the Blight struck.

Callaghan and the Carrolls ... cut two acres and half of Bernards oats yesterday and carried it off the lands. I went myself on the lands to protect the oats being

carried off, but all in vain. I had three of the police from Kilmallock with me and ... we were beattin off with stones and sickels. They were in number more than 70 men and women .... I went from the lands to Kilfinane [about 8 miles away] to get more police .... Four of them were taken and bailed for Friday which is the Court day in Kilmallock

The charges were dropped again. The next March, Murnane came again with another bailiff to talk John into leaving the land, but John allegedly grabbed a pike and threatened to run anyone through who came near him. On May 13, John again wrote SK:

Is there anything more unfair ... than to take the part of one man having a large family and whose Ancestors have lived on this Estate for the last Century, and hand it over to another [John Bernard] ... who has no original claim, save his being a Lot holder ... to the late Thomas White [a middleman] .... Leave me my little holding and you shall be honestly repaid what money you gave me

SK wrote to Murnane to offer more money, but Murnane refused and had John arrested again. The charges are unknown, but Murnane now sought an ejectment decree.

Stewart Maxwell, a senior employee of SK, decided to visit Callaghan in jail. He reported that "the fellow is in a wretched state of mind and says that ... he does not care very much what happens to him"; however, "he at last consented to take £15 and to get his potatoes" in return for quietly giving up possession. It seems, following further pressure from Bennett, that the case against Callaghan was struck off the list.

On August 7, 1845, Murnane informed SK that he had gotten John off the land, seized anything worthwhile, and left seven men on the land to guard it at night. On the 10th, he wrote:

the state of Callaghan's former lands, as follows: “2 acres of Bad oats, 1 ½ ditto of potatoes, ½ meaddowing, 3 ¼ ditto pasture or waist land.

John was off the final 7.25 acres of the land, but not off the estate. He moved his family into a bothán (a fourth-class house which was a mere hovel made of mud and sticks) owned by neighbor John Keeffe, probably related to his son James’ godmother. Then the Blight struck.

In the Autumn of 1845, a blight appeared unexpectedly among the potatoes. It was a black mold or fungus that caused much of the crop to rot in the fields, marking the beginning of the Great Famine (An Gorta Mor). The unique feature of the potato blight was the speed with which it spread. Eye witnesses said that a crop of potatoes in a field would be perfect in the morning time and by evening would be a rotting mass.

Many varieties of potatoes had been grown in Ireland since its introduction in 1610 at Rathkeale, Clare, but, by the time of the Famine, the main variety was the Lumper. It had a high yield, but was not very palatable. It had originally been introduced as animal feed, but its high yield made it preferable as human food during the early 19th century when the population was growing rapidly.

Four successive blighted harvests followed. Connacht and Munster were hit worst, where entire populations of towns had to abandon their homes and take to the road, searching for food. Bodies littered the countryside. Many died trying to eat weeds and any plants they could find, giving rise to a medical condition called “green mouth” from the stains. Many more died of typhus or dysentery. Between 1846 and 1849, over a million people died and another million emigrated, causing a population drop of almost 25 percent on the island. Mass graves appeared everywhere, and churches and towns could not properly update the death records. Nine-year-old William would have seen people dying all around him daily for years.

East Limerick, like East Galway and Roscommon, suffered slightly less than some other areas nearby because the land was more fertile and were planted with grains like wheat, barley, and oats, as well as potatoes. The famine was particularly bad in the west Cork area and in Kerry, but it was also bad in and around Charleville. 72% of the people living in bothán near Charleville were wiped out by the famine. But not all people suffered during these years as some wealthy Irish Catholic middle-class farmers did very well buying land from tenants whose small holdings had been affected by the blight. With their potato crop failing, they had to sell their plot of land to buy food for their family and/or their passage out of the country. Mount Blakeney was devastated. In 1841, there were 40 houses and 336 people living there. By 1851, only 55 people were left in 15 houses. By 1881, there were only 61 people in seven houses.

Luckily, John’s “people-in-law” came to his aid again. Effin had been hit slightly less hard. Their population dropped from 487 people in 78 houses to 313 people in 47 houses by 1851. Nora had inherited one acre of land in Effin from her father in 1842. Her brother James sublet some of his own fields and a stone house on the Robert Maxwell Estate. James and his brother John had taken up the 42 acres of sections 27 and 28 which their father Michael Carroll had rented previously, as noted in the 1823 Tithe Applotment Books. The Callaghans’ new fields were denoted on Griffith’s Valuation map in 1853 as 28a. They were just north of the old Effin Churchyard and east of a holy well.

The Mountblakeney estate faired about as well as any other land in the West during the Famine. Rent loss in 1845-48 was significant. Stewart & Kincaid applied for and received a government grant for road and land improvements which they used to pay tenants for work in order to keep body and soul together, but it was not enough. Population dropped though death and immigration. Lady Fitzgerald paid for some of the tenants to move to America or Australia, but her coffers were not limitless.

In 1833, the Tithe Applotment books showed 25 tenants. By 1851 and Griffith’s Valuation, there were only thirteen tenants and four vacant sections of land. Besides the Callaghans, the Bernard brothers were gone as were four of the five Keefes. The younger Patrick Donovan was still there with his son James. Edmund Kelleher, who was mentioned in SK letters as one to take over the Callaghan lease instead of John Bernard, was there on section 8. It is unknown if section 8 was where the Callaghan land was, though.

Many varieties of potatoes had been grown in Ireland since its introduction in 1610 at Rathkeale, Clare, but, by the time of the Famine, the main variety was the Lumper. It had a high yield, but was not very palatable. It had originally been introduced as animal feed, but its high yield made it preferable as human food during the early 19th century when the population was growing rapidly.

Four successive blighted harvests followed. Connacht and Munster were hit worst, where entire populations of towns had to abandon their homes and take to the road, searching for food. Bodies littered the countryside. Many died trying to eat weeds and any plants they could find, giving rise to a medical condition called “green mouth” from the stains. Many more died of typhus or dysentery. Between 1846 and 1849, over a million people died and another million emigrated, causing a population drop of almost 25 percent on the island. Mass graves appeared everywhere, and churches and towns could not properly update the death records. Nine-year-old William would have seen people dying all around him daily for years.

East Limerick, like East Galway and Roscommon, suffered slightly less than some other areas nearby because the land was more fertile and were planted with grains like wheat, barley, and oats, as well as potatoes. The famine was particularly bad in the west Cork area and in Kerry, but it was also bad in and around Charleville. 72% of the people living in bothán near Charleville were wiped out by the famine. But not all people suffered during these years as some wealthy Irish Catholic middle-class farmers did very well buying land from tenants whose small holdings had been affected by the blight. With their potato crop failing, they had to sell their plot of land to buy food for their family and/or their passage out of the country. Mount Blakeney was devastated. In 1841, there were 40 houses and 336 people living there. By 1851, only 55 people were left in 15 houses. By 1881, there were only 61 people in seven houses.

Luckily, John’s “people-in-law” came to his aid again. Effin had been hit slightly less hard. Their population dropped from 487 people in 78 houses to 313 people in 47 houses by 1851. Nora had inherited one acre of land in Effin from her father in 1842. Her brother James sublet some of his own fields and a stone house on the Robert Maxwell Estate. James and his brother John had taken up the 42 acres of sections 27 and 28 which their father Michael Carroll had rented previously, as noted in the 1823 Tithe Applotment Books. The Callaghans’ new fields were denoted on Griffith’s Valuation map in 1853 as 28a. They were just north of the old Effin Churchyard and east of a holy well.

The Mountblakeney estate faired about as well as any other land in the West during the Famine. Rent loss in 1845-48 was significant. Stewart & Kincaid applied for and received a government grant for road and land improvements which they used to pay tenants for work in order to keep body and soul together, but it was not enough. Population dropped though death and immigration. Lady Fitzgerald paid for some of the tenants to move to America or Australia, but her coffers were not limitless.

In 1833, the Tithe Applotment books showed 25 tenants. By 1851 and Griffith’s Valuation, there were only thirteen tenants and four vacant sections of land. Besides the Callaghans, the Bernard brothers were gone as were four of the five Keefes. The younger Patrick Donovan was still there with his son James. Edmund Kelleher, who was mentioned in SK letters as one to take over the Callaghan lease instead of John Bernard, was there on section 8. It is unknown if section 8 was where the Callaghan land was, though.

The Callaghans survived. But even after the Famine was considered over (1849 or 1852, depending on who you take as the source), the crops were thin for a family of nine. In 1851, a gold strike in Victoria led to a depopulation in South Australia as men rushed to make it rich. Adelaide and surrounding areas lost much of its labor force and pushed for increased immigration. In 1855, a new Passenger Act was enacted, and John and Nora’s daughter Mary decided to immigrate to Adelaide, South Australia, for work as a domestic servant. She joined 334 other immigrants—including three Carroll cousins—at the Port of Cobh and boarded the sailing ship South Sea out of Plymouth, Captain George Geere. After almost three months at sea, she arrived at Adelaide on July 30, 1855.

It is not known who she worked for in Australia, but, after two years, she married John Byrnes (or Burns) on September 6, 1857, at St. Patrick’s Church in Adelaide. Thirteen months later, she bore John and Nora’s first grandchild, a son named Edmund. Nora did not live to see the birth (her death date is unknown), but John and the rest of the family arrived in Adelaide with a week to spare.

Nora Carroll died sometime between 1850 and 1858. She did not see her 40th birthday. She is probably buried in the Effin Graveyard, but no headstone exists. Likely John could not afford one.

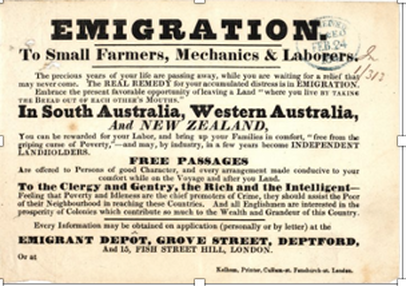

While the potato blight seemed to be under control, crops still occasionally failed, and 1858 saw a return to famine levels. The clause in the Poor Law Act which had allowed for the government support of emigration came into effect again in 1858, this time to transport men to Australia where they were needed because so many farm hands had left the fields during the Gold Rush of 1852-3. Another round of the crop failures, political unrest, the rise of Irish Republican Brotherhood, and the death of Nora all together must have convinced John to emigrate the family.

The process required that one apply for assisted passage and wait until they could be examined. Classes eligible for free passage, according to the Passage Regulations South Australia 1862 (http://www.theshipslist.com/ships/australia/regulations1862.shtml), were:

I. Married agricultural laborers, shepherds, herdsmen, and copper miners, not exceeding forty-five years of age.

II. Single men, or widowers without children under sixteen, of any of the above classes, not exceeding forty years of age.

III. Single female domestic servants, or widows without children under sixteen, not exceeding thirty-five years of age.

IV. Married mechanics (when required in the Colony), such as masons, bricklayers, blacksmiths and farriers, wheelwrights, sawyers, carpenters, &c., also gardeners, not exceeding forty-five years of age.

V. Single men of class iv. (when required), not exceeding forty years of age.

VI. The wives and children of married immigrants.

Eligible candidates were clearly defined:

The candidates must be in the habit of working for wages at one of the callings mentioned above, and must be going out with the intention of working for hire in that calling. They must be sober, industrious, of good moral character, in good health, free from all mental and bodily defects, within the ages specified, appear physically to be capable of labor, and have been vaccinated or had the small-pox.

Passages cannot be granted to persons intending to proceed to the other Australian Colonies; to persons in the habitual receipt of parish relief; to widowers and widows with young children; to parents without all their children under sixteen then in Britain; to children under sixteen without their parents; to husbands without their wives, or wives without their husbands; to single men over forty; to single women over thirty-five; to single women who have had illegitimate children; or to persons who have not arranged with their creditors.

It is unclear how John was accepted, since widowers over 40 or with children under 16 were excluded. Somehow, he was accepted. Then everyone had to gather the right outfit (luggage) at their own expense.

Candidates must find their own outfit, which will be inspected before embarkation by an officer duly authorized by the Emigration Agent. The smallest quantity that will be allowed is for each male over twelve, six shirts, six pairs of stockings, two warm flannel shirts, two pairs of new shoes or boots, two complete suits of strong exterior clothing, four towels, and 2lbs. of marine soap; and for each female over twelve, six shifts, two flannel petticoats, six pairs of stockings, two pairs of strong boots or shoes, two strong gowns (one of which must be made of a warm material), four towels, and 2lbs. of marine soap. N.B. If any difficulty is experienced in procuring good marine soap where the applicants reside, there will be ample opportunity for purchasing it after their arrival at the depot.

Two or three coloured shirts for men, and an extra supply of flannel for women and children, are very desirable. The quantity of baggage for each person over twelve must not exceed twenty cubic or solid feet, nor half a ton in weight. It must be closely packed in one or more strong boxes or cases not exceeding fifteen cubic feet each. Larger packages and extra baggage, if taken at all, must be paid for. Mattresses and feather beds, firearms, and offensive weapons, wines, spirits, beer, gunpowder, percussion caps, lucifer matches, and any dangerous and noxious articles, cannot be taken by emigrants.

Once in South Australia, assisted passengers were required to stay there and work for 2 years. This provision was to keep them from running away to the gold fields of higher paying work in Sydney or Melbourne.

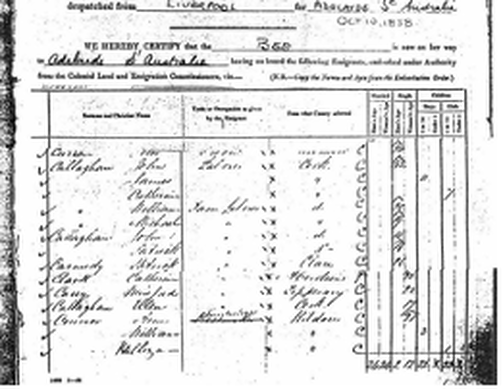

In July of 1858, a 42-year-old John Callaghan and his family boarded the Bee—a 1200-ton ship built in Boston in 1853 and commanded by Captain William Raisbeck—with 418 other immigrants, bound for Australia. They arrived in Adelaide, South Australia, on October 9, 1858, after a journey of 98 days during which six people died (five of them children under one) and six more were born aboard the ship. Details of the voyage were posted in The South Australian Advertiser, Monday 11 October 1858:

The ship Bee, from Liverpool, arrived in our waters on Saturday, the 9th instant, having made her voyage in 98 days, although having very adverse winds to contend with throughout her progress. She reports leaving Liverpool on the 2nd July, and from her log we extract the following particulars of her voyage:

Lost sight of land two days after taking her departure from port, with a strong gale from the westward, sighting the most north-westerly island of the Cape de Verd group (St. Antonio) on July 22nd, and did not fall in with the north-east trade winds until reaching the latitude (St. Antonio), during which the vessel ran the average speed of 280 miles in 24 hours. In lat. 12° N., lost the north-east trade, and fell in with the southerly monsoons, which invariably blew in this latitude during the months of August, September, and October. Captain Raisbeck reports them as veering during the period his ship was running them down from S. to S.W., and remarkably scant, driving his vessel far to the westward, fully 5° from the usual course, which is fully borne out by her report of having crossed the equator in longitude 31° 38' W. This transpired on July 29th, 27 days out. Shortly after sighting the Island or Fernando de Noranha, fell in with the S.E. trades, which were remarkably light and southerly, the course of the ship being parallel with the Brazilian coast, within 40 miles of land; from thence to the meridian of the Cape of Good Hope, which was reached on August 30th, occupied 20 days, and here experienced strong easterly winds for ten days, veering to the S.E., driving her northward. From the meridian of 100°, to reaching this port, 20 days have transpired.

It is not known who she worked for in Australia, but, after two years, she married John Byrnes (or Burns) on September 6, 1857, at St. Patrick’s Church in Adelaide. Thirteen months later, she bore John and Nora’s first grandchild, a son named Edmund. Nora did not live to see the birth (her death date is unknown), but John and the rest of the family arrived in Adelaide with a week to spare.

Nora Carroll died sometime between 1850 and 1858. She did not see her 40th birthday. She is probably buried in the Effin Graveyard, but no headstone exists. Likely John could not afford one.

While the potato blight seemed to be under control, crops still occasionally failed, and 1858 saw a return to famine levels. The clause in the Poor Law Act which had allowed for the government support of emigration came into effect again in 1858, this time to transport men to Australia where they were needed because so many farm hands had left the fields during the Gold Rush of 1852-3. Another round of the crop failures, political unrest, the rise of Irish Republican Brotherhood, and the death of Nora all together must have convinced John to emigrate the family.

The process required that one apply for assisted passage and wait until they could be examined. Classes eligible for free passage, according to the Passage Regulations South Australia 1862 (http://www.theshipslist.com/ships/australia/regulations1862.shtml), were:

I. Married agricultural laborers, shepherds, herdsmen, and copper miners, not exceeding forty-five years of age.

II. Single men, or widowers without children under sixteen, of any of the above classes, not exceeding forty years of age.

III. Single female domestic servants, or widows without children under sixteen, not exceeding thirty-five years of age.

IV. Married mechanics (when required in the Colony), such as masons, bricklayers, blacksmiths and farriers, wheelwrights, sawyers, carpenters, &c., also gardeners, not exceeding forty-five years of age.

V. Single men of class iv. (when required), not exceeding forty years of age.

VI. The wives and children of married immigrants.

Eligible candidates were clearly defined:

The candidates must be in the habit of working for wages at one of the callings mentioned above, and must be going out with the intention of working for hire in that calling. They must be sober, industrious, of good moral character, in good health, free from all mental and bodily defects, within the ages specified, appear physically to be capable of labor, and have been vaccinated or had the small-pox.

Passages cannot be granted to persons intending to proceed to the other Australian Colonies; to persons in the habitual receipt of parish relief; to widowers and widows with young children; to parents without all their children under sixteen then in Britain; to children under sixteen without their parents; to husbands without their wives, or wives without their husbands; to single men over forty; to single women over thirty-five; to single women who have had illegitimate children; or to persons who have not arranged with their creditors.

It is unclear how John was accepted, since widowers over 40 or with children under 16 were excluded. Somehow, he was accepted. Then everyone had to gather the right outfit (luggage) at their own expense.

Candidates must find their own outfit, which will be inspected before embarkation by an officer duly authorized by the Emigration Agent. The smallest quantity that will be allowed is for each male over twelve, six shirts, six pairs of stockings, two warm flannel shirts, two pairs of new shoes or boots, two complete suits of strong exterior clothing, four towels, and 2lbs. of marine soap; and for each female over twelve, six shifts, two flannel petticoats, six pairs of stockings, two pairs of strong boots or shoes, two strong gowns (one of which must be made of a warm material), four towels, and 2lbs. of marine soap. N.B. If any difficulty is experienced in procuring good marine soap where the applicants reside, there will be ample opportunity for purchasing it after their arrival at the depot.

Two or three coloured shirts for men, and an extra supply of flannel for women and children, are very desirable. The quantity of baggage for each person over twelve must not exceed twenty cubic or solid feet, nor half a ton in weight. It must be closely packed in one or more strong boxes or cases not exceeding fifteen cubic feet each. Larger packages and extra baggage, if taken at all, must be paid for. Mattresses and feather beds, firearms, and offensive weapons, wines, spirits, beer, gunpowder, percussion caps, lucifer matches, and any dangerous and noxious articles, cannot be taken by emigrants.

Once in South Australia, assisted passengers were required to stay there and work for 2 years. This provision was to keep them from running away to the gold fields of higher paying work in Sydney or Melbourne.

In July of 1858, a 42-year-old John Callaghan and his family boarded the Bee—a 1200-ton ship built in Boston in 1853 and commanded by Captain William Raisbeck—with 418 other immigrants, bound for Australia. They arrived in Adelaide, South Australia, on October 9, 1858, after a journey of 98 days during which six people died (five of them children under one) and six more were born aboard the ship. Details of the voyage were posted in The South Australian Advertiser, Monday 11 October 1858:

The ship Bee, from Liverpool, arrived in our waters on Saturday, the 9th instant, having made her voyage in 98 days, although having very adverse winds to contend with throughout her progress. She reports leaving Liverpool on the 2nd July, and from her log we extract the following particulars of her voyage:

Lost sight of land two days after taking her departure from port, with a strong gale from the westward, sighting the most north-westerly island of the Cape de Verd group (St. Antonio) on July 22nd, and did not fall in with the north-east trade winds until reaching the latitude (St. Antonio), during which the vessel ran the average speed of 280 miles in 24 hours. In lat. 12° N., lost the north-east trade, and fell in with the southerly monsoons, which invariably blew in this latitude during the months of August, September, and October. Captain Raisbeck reports them as veering during the period his ship was running them down from S. to S.W., and remarkably scant, driving his vessel far to the westward, fully 5° from the usual course, which is fully borne out by her report of having crossed the equator in longitude 31° 38' W. This transpired on July 29th, 27 days out. Shortly after sighting the Island or Fernando de Noranha, fell in with the S.E. trades, which were remarkably light and southerly, the course of the ship being parallel with the Brazilian coast, within 40 miles of land; from thence to the meridian of the Cape of Good Hope, which was reached on August 30th, occupied 20 days, and here experienced strong easterly winds for ten days, veering to the S.E., driving her northward. From the meridian of 100°, to reaching this port, 20 days have transpired.

The Callaghan family on the passenger list included the father, John (42), along with his children William (20), Michael (19), Patrick (17), John (16), James (11), and Kate (7). Effin Parish records only exist for Kate and James and do not go back before 1843, though Michael’s baptism in Effin was confirmed by his marriage record. We do not have independent confirmation of the other brothers’ birth dates and places. On the passenger list published at http://www.theshipslist.com/ships/australia/bee1858.shtml, the family was designated with an N, meaning they were Nominee Emigrants.

One odd mystery arises from this shipping list: William (20) cannot be John’s son. John’s son William left for America in 1854 and ended up in Minnesota. Multiple sources attest to this, and William the son’s whereabouts are chronicled in The History of Dakota County (1910). The William on the ship might be a brother or nephew or cousin of John’s. John’s children James and Kate had a godfather named William Callaghan, possibly Mystery William’s father. But there are no records of another Callaghan in Effin Parish. Or maybe Mystery William was a Carroll nephew running away from home in disguise. We may never know.

John Jr, Pat, and James are also listed on the Incoming and outgoing Passenger Lists as having attended school aboard the Bee. It is noted that none of them had education in reading, writing, nor arithmetic at the start of the journey. After 57 days of schooling under Schoolmaster of the Ship John A. Boyd (himself listed as a General Emigrant), they had progressed through the 3rd book of reading instruction. John was noted as being “very perseverant,” James was “most attentive,” and Pat was “very attentive.” James, being younger, was still writing “large,” but his brothers had both progressed to “small” writing. They achieved different levels mathematically, but there is no legend explaining the designations of C.M, C.S., and C.A., respectively. William and Michael attended the Men’s school. They progressed from S.A. to S.D., indicating they came aboard with some education in the three R’s. Ellen and Kate did not attend the school.

According to a report by the Australian Immigration Agent, H. Duncan, MD,

The Ship Frenchman and every vessel since she arrived have brought a certain proportion of emigrants selected by Mr. Moorhouse, the emigration agent in London. I can state strongly that the class of emigrants selected by that gentlemen are of a very superior description, when compared with those selected by the Commissioners. Mr. Moorhouse has completely disproven the assertion of the Commissioners that no really good domestic servants could be induced to emigrate.

John and his sons would have been among those “gentlemen of a very superior description.”

According to Wikipedia:

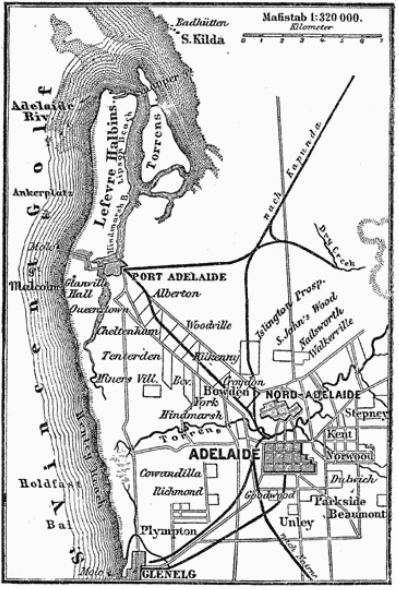

Adelaide is situated on the Adelaide Plains north of the Fleurieu Peninsula, between the Gulf St Vincent in the west and the Mount Lofty Ranges in the east. Its metropolitan area extends 20 km (12 mi) from the coast to the foothills of the Mount Lofty Ranges, and stretches 96 km (60 mi) from Gawler in the north to Sellicks Beach in the south.

One odd mystery arises from this shipping list: William (20) cannot be John’s son. John’s son William left for America in 1854 and ended up in Minnesota. Multiple sources attest to this, and William the son’s whereabouts are chronicled in The History of Dakota County (1910). The William on the ship might be a brother or nephew or cousin of John’s. John’s children James and Kate had a godfather named William Callaghan, possibly Mystery William’s father. But there are no records of another Callaghan in Effin Parish. Or maybe Mystery William was a Carroll nephew running away from home in disguise. We may never know.

John Jr, Pat, and James are also listed on the Incoming and outgoing Passenger Lists as having attended school aboard the Bee. It is noted that none of them had education in reading, writing, nor arithmetic at the start of the journey. After 57 days of schooling under Schoolmaster of the Ship John A. Boyd (himself listed as a General Emigrant), they had progressed through the 3rd book of reading instruction. John was noted as being “very perseverant,” James was “most attentive,” and Pat was “very attentive.” James, being younger, was still writing “large,” but his brothers had both progressed to “small” writing. They achieved different levels mathematically, but there is no legend explaining the designations of C.M, C.S., and C.A., respectively. William and Michael attended the Men’s school. They progressed from S.A. to S.D., indicating they came aboard with some education in the three R’s. Ellen and Kate did not attend the school.

According to a report by the Australian Immigration Agent, H. Duncan, MD,

The Ship Frenchman and every vessel since she arrived have brought a certain proportion of emigrants selected by Mr. Moorhouse, the emigration agent in London. I can state strongly that the class of emigrants selected by that gentlemen are of a very superior description, when compared with those selected by the Commissioners. Mr. Moorhouse has completely disproven the assertion of the Commissioners that no really good domestic servants could be induced to emigrate.

John and his sons would have been among those “gentlemen of a very superior description.”

According to Wikipedia:

Adelaide is situated on the Adelaide Plains north of the Fleurieu Peninsula, between the Gulf St Vincent in the west and the Mount Lofty Ranges in the east. Its metropolitan area extends 20 km (12 mi) from the coast to the foothills of the Mount Lofty Ranges, and stretches 96 km (60 mi) from Gawler in the north to Sellicks Beach in the south.

Adelaide, named after the wife of King William IV, was founded in 1836 on land that had been occupied by 20 or so semi-nomadic, aboriginal clans known as the Kaurna. By the time of colonization, most of the Kaurna had died from small pox. Adelaide was established as a planned colony of free immigrants, promising civil liberties and freedom from religious persecution, based upon the ideas of Edward Gibbon Wakefield. Wakefield had read accounts of Australian settlement while in prison in London for attempting to abduct an heiress, and realized that the eastern colonies suffered from a lack of available labor, due to the practice of giving land grants to all arrivals. Wakefield's idea was for the Government to survey and sell the land at a rate that would maintain land values high enough to be unaffordable for laborers and journeymen. Funds raised from the sale of land were to be used to bring out working-class emigrants—like the Callaghans—who would have to work hard for the monied settlers to afford their own land. As a result of this policy, Adelaide does not share the convict settlement history of other Australian cities.

During the 30 years that John lived there, Adelaide grew and developed into a major city. In 1856, South Australia had become a self-governing colony of 109,917 people with the ratification of a new constitution by the British parliament. In 1860, the Thorndon Park reservoir was opened, finally providing an alternative water source to the now turbid River Torrens. Gas street lighting was implemented in 1867. The University of Adelaide was founded in 1874, and the South Australian Art Gallery opened in 1881.

Sometime in his first four years in South Australia, John met a widow named Mary Anne Philips.

Mary Anne Cleary was born in or near Ennis, County Clare, sometime between 1825 and 1831. Her parents were John and Margaret Cleary. Not much is known about her. Her marriage record says she was 35 in 1862, putting her birth at 1831. But her first child was born in South Australia in 1843, which would have made her 14 years old—highly unlikely. It is believed that she arrived in South Australia aboard the vessel Birman on 7th December 1840 with her parents and siblings.

She was the widow of Thomas Philips (1815 – 1856), a teamster in Morphett Vale, who died in an accident wherein he tumbled out of the dray for some reason and his bullock team drove over him. Mary Anne was left with four young children, the youngest barely a year old. How John and Mary met is unknown. They married at St. Patrick’s Chapel, Adelaide, on February 2, 1862.

Mary had married John Burns in 1857 and settled in Hectorville. By 1863, John brought the family to live near her there as well and, initially, probably squatted on the land. Having come halfway around the world, it was sometimes easier for immigrants to keep moving. Shortly after the two years required by their paid passage were up, other siblings moved on. By 1860, James and Michael had moved to Melbourne. James joined the Hibernian Australasian Catholic Benefit Society (HACBS)—though, in June of 1887, he returned to Adelaide where he lived until his death in 1939 at the age of 94. Michael left Melbourne five years after moving there and sailed to California with his wife and two children. They would become successful wheat and sheep ranchers on the Sacramento Delta and have two more children there. Patrick sailed for New Zealand in 1861 where he would meet and marry Emma Ware in 1867. He would become a successful cattle rancher in Okains Bay, and his daughter and only child would marry into the prominent Birdling family.

During the 30 years that John lived there, Adelaide grew and developed into a major city. In 1856, South Australia had become a self-governing colony of 109,917 people with the ratification of a new constitution by the British parliament. In 1860, the Thorndon Park reservoir was opened, finally providing an alternative water source to the now turbid River Torrens. Gas street lighting was implemented in 1867. The University of Adelaide was founded in 1874, and the South Australian Art Gallery opened in 1881.

Sometime in his first four years in South Australia, John met a widow named Mary Anne Philips.

Mary Anne Cleary was born in or near Ennis, County Clare, sometime between 1825 and 1831. Her parents were John and Margaret Cleary. Not much is known about her. Her marriage record says she was 35 in 1862, putting her birth at 1831. But her first child was born in South Australia in 1843, which would have made her 14 years old—highly unlikely. It is believed that she arrived in South Australia aboard the vessel Birman on 7th December 1840 with her parents and siblings.

She was the widow of Thomas Philips (1815 – 1856), a teamster in Morphett Vale, who died in an accident wherein he tumbled out of the dray for some reason and his bullock team drove over him. Mary Anne was left with four young children, the youngest barely a year old. How John and Mary met is unknown. They married at St. Patrick’s Chapel, Adelaide, on February 2, 1862.

Mary had married John Burns in 1857 and settled in Hectorville. By 1863, John brought the family to live near her there as well and, initially, probably squatted on the land. Having come halfway around the world, it was sometimes easier for immigrants to keep moving. Shortly after the two years required by their paid passage were up, other siblings moved on. By 1860, James and Michael had moved to Melbourne. James joined the Hibernian Australasian Catholic Benefit Society (HACBS)—though, in June of 1887, he returned to Adelaide where he lived until his death in 1939 at the age of 94. Michael left Melbourne five years after moving there and sailed to California with his wife and two children. They would become successful wheat and sheep ranchers on the Sacramento Delta and have two more children there. Patrick sailed for New Zealand in 1861 where he would meet and marry Emma Ware in 1867. He would become a successful cattle rancher in Okains Bay, and his daughter and only child would marry into the prominent Birdling family.

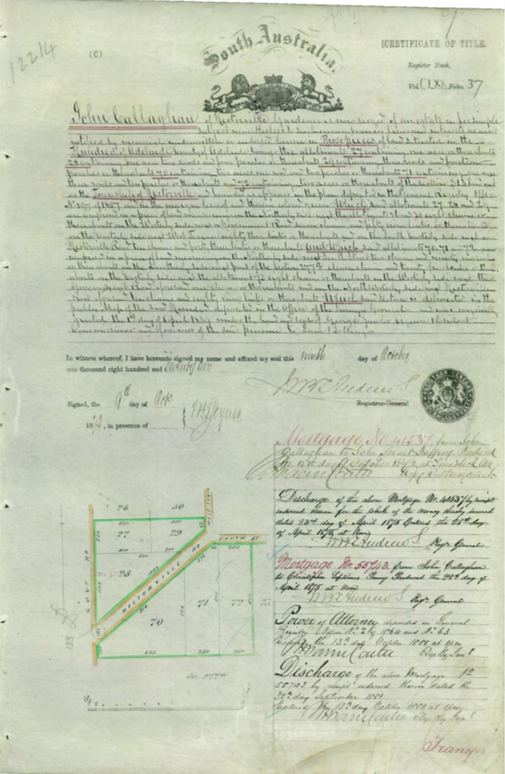

John followed the lead of his son-in-law by buying land and becoming a market gardener. On October 9, 1872, he took out a mortgage and bought Allotments 27, 28, 29 and 70, 71, 72 next door to his daughter and her husband. This amounted to about 9 acres of land. He then built a four-room house made of concrete.

Market gardening was and is small-scale farming larger than a home garden, but small enough that many of the principles of gardening are applicable. . Unlike large, industrial farms, which practice monoculture and mechanization, many different crops and varieties are grown and more manual labor is needed when gardening techniques are used.

John began to sell the land off in 1881. By 1897, it was owned by before selling it to James Benjamin Pierson. The Piersons kept it for three generations before selling the land to the Starlight Drive-in Theatre in 1951. Pierson’s grandson Jim participated in the Campbelltown City Council Oral History Project: Our Fruitful Record: A History of Market Gardening in Campbelltown (2018) and discussed the history of market gardening. It is unknown what crops John grew, but the Piersons grew celery and cauliflower. Jim Pierson explained:

Oh well, those days, cauliflowers grew, and of course, you used to go through and cut what were called the fit cauliflowers, the ones that were ready, they weren’t all ready at the same time. Today, the hybrid varieties tend to come ready all at once, but those days, you’d have to cut through maybe two, three or four times, and you carry them out to the end where you had a truck, where you could stack them up, and get in there with a truck to load them up. That’s how it was done. It wouldn’t matter if it was pouring with rain, you’re bogged up to your knees, you still had to cut the load and get them out and get them loaded up. The market didn’t stop.

Young John also remained in the area, becoming a gardener (probably with his father) in Hectorville and, later, in Modbury. It is likely that he was the John Callaghan who married Elizabeth Murphy (daughter of Timothy Murphy) on November 5, 1867 at St. Patrick’s Church in Adelaide. They do not seem to have had any children.

Kate was a domestic servant in Waterloo where she was admitted to the hospital there on January 28, 1868. She had contracted syphilis. She was released on March 2nd. What became of her after that is unknown. Ellen was a domestic servant in Adelaide, but nothing of her fate is known, either.

As noted above, in 1858, the first of John and Nora’s 23 grandchildren arrived with the birth of Mary’s son Edmund Burns. He was likely named after his paternal grandfather. All the grandchildren were born within John’s lifetime, but he would only meet 12 of them, at most. William’s eight children would all be born in America. Two of Michael’s four would also be born in California. Patrick’s only daughter would be born in New Zealand. Starting in 1889, John would have 33 great-grandchildren. Four would be born before he died.

Market gardening was and is small-scale farming larger than a home garden, but small enough that many of the principles of gardening are applicable. . Unlike large, industrial farms, which practice monoculture and mechanization, many different crops and varieties are grown and more manual labor is needed when gardening techniques are used.

John began to sell the land off in 1881. By 1897, it was owned by before selling it to James Benjamin Pierson. The Piersons kept it for three generations before selling the land to the Starlight Drive-in Theatre in 1951. Pierson’s grandson Jim participated in the Campbelltown City Council Oral History Project: Our Fruitful Record: A History of Market Gardening in Campbelltown (2018) and discussed the history of market gardening. It is unknown what crops John grew, but the Piersons grew celery and cauliflower. Jim Pierson explained:

Oh well, those days, cauliflowers grew, and of course, you used to go through and cut what were called the fit cauliflowers, the ones that were ready, they weren’t all ready at the same time. Today, the hybrid varieties tend to come ready all at once, but those days, you’d have to cut through maybe two, three or four times, and you carry them out to the end where you had a truck, where you could stack them up, and get in there with a truck to load them up. That’s how it was done. It wouldn’t matter if it was pouring with rain, you’re bogged up to your knees, you still had to cut the load and get them out and get them loaded up. The market didn’t stop.

Young John also remained in the area, becoming a gardener (probably with his father) in Hectorville and, later, in Modbury. It is likely that he was the John Callaghan who married Elizabeth Murphy (daughter of Timothy Murphy) on November 5, 1867 at St. Patrick’s Church in Adelaide. They do not seem to have had any children.

Kate was a domestic servant in Waterloo where she was admitted to the hospital there on January 28, 1868. She had contracted syphilis. She was released on March 2nd. What became of her after that is unknown. Ellen was a domestic servant in Adelaide, but nothing of her fate is known, either.

As noted above, in 1858, the first of John and Nora’s 23 grandchildren arrived with the birth of Mary’s son Edmund Burns. He was likely named after his paternal grandfather. All the grandchildren were born within John’s lifetime, but he would only meet 12 of them, at most. William’s eight children would all be born in America. Two of Michael’s four would also be born in California. Patrick’s only daughter would be born in New Zealand. Starting in 1889, John would have 33 great-grandchildren. Four would be born before he died.

John died on November 23, 1890. He was 74 years old. No obituary or death notice has been found. He was laid to rest in West Terrace Cemetery in Adelaide, where he would later be joined by his children Mary, John, and James, his granddaughter Ellen Burns Davis and her husband Frank, and their daughter Eileen Davis Hartmann. The gravestones were vandalized later, but descendants Michael and David Guerin preserved them by mounting them onto a cement base. John’s inscription proudly stated he was “A Native of Effin, County Limerick, Ireland.” They got his age wrong, though.

Mary Anne lived six more years, dying on April 25, 1896, in Norwood, South Australia

John led a difficult life of hardship and loss, but, in the second half of his life, he saw prosperity in his new home. And he got out just in time. In the 1890s, Australia was affected by a severe economic depression, ending a hectic era of land booms and tumultuous expansionism. Financial institutions in Melbourne and banks in Sydney closed. The national fertility rate fell and immigration was reduced to a trickle. The value of South Australia's exports nearly halved. Drought and poor harvests from 1884 compounded the problems, with many families leaving for Western Australia. Adelaide was not as badly hit as the larger gold-rush cities of Sydney and Melbourne, and silver and lead discoveries at Broken Hill provided some relief. Only one year of deficit was recorded, but the price paid was retrenchments and lean public spending. Wine and copper were the only industries not to suffer a downturn.

John and Nora’s children survived and thrived, though. They had good examples of strength and perseverence to follow. There are scores of Callaghan descendants around the world, though the surname ended with Dolores Callaghan Quattrin and only exists among the descendants as a middle name. While John had an arduous, but long and fulfilling life, Nora’s was relatively short. Together they survived arrest, eviction, and the Great Famine. Apart, John experienced relocation around the world and the growth of the family. Their lives are part of the fabric of who we are, and they deserve to be remembered and honored.

John led a difficult life of hardship and loss, but, in the second half of his life, he saw prosperity in his new home. And he got out just in time. In the 1890s, Australia was affected by a severe economic depression, ending a hectic era of land booms and tumultuous expansionism. Financial institutions in Melbourne and banks in Sydney closed. The national fertility rate fell and immigration was reduced to a trickle. The value of South Australia's exports nearly halved. Drought and poor harvests from 1884 compounded the problems, with many families leaving for Western Australia. Adelaide was not as badly hit as the larger gold-rush cities of Sydney and Melbourne, and silver and lead discoveries at Broken Hill provided some relief. Only one year of deficit was recorded, but the price paid was retrenchments and lean public spending. Wine and copper were the only industries not to suffer a downturn.

John and Nora’s children survived and thrived, though. They had good examples of strength and perseverence to follow. There are scores of Callaghan descendants around the world, though the surname ended with Dolores Callaghan Quattrin and only exists among the descendants as a middle name. While John had an arduous, but long and fulfilling life, Nora’s was relatively short. Together they survived arrest, eviction, and the Great Famine. Apart, John experienced relocation around the world and the growth of the family. Their lives are part of the fabric of who we are, and they deserve to be remembered and honored.